Helmut Lachenmann, who celebrated his 89th birthday at the end of last month, is widely considered to be Germany’s greatest living composer. A generation younger than Karlheinz Stockhausen and Hans Werner Henze, Lachenmann is a big deal at home, feted by festivals dealing in modern composition, but also increasingly by more mainstream classical institutions. Simon Rattle, in 2019, performed his 40-minute My Melodies with the Berlin Philharmonic, no less. Had a pandemic not intervened, followed by Rattle’s abrupt departure as music director of the London Symphony Orchestra, perhaps he would have repeated the feat in London. Instead, that task fell to the conductor Ilan Volkov, who, at the Barbican last week, led the LSO through Lachenmann’s labyrinth of rude noises and hardly-there orchestral whispers.

With Rattle gone, the LSO could have made life easy for themselves by discreetly jettisoning Lachenmann’s piece, though praise be that they didn’t. In truth, his music has never been an easy sell in this Britain—Tanzsuite mit Deutschlandlied, for string quartet and orchestra, performed by the Arditti Quartet and Bamberg Symphony Orchestra under Jonathan Nott at the 2013 Proms, provoked a mass mutiny and walkout among the audience, most of whom had no doubt come to hear Mahler’s Fifth in the second half. At the Barbican, a near capacity house listened attentively, with only a few people dashing for the exit—but there’s still a long way to go, I think, until classical audiences in the UK learn to truly love Lachenmann’s music.

Why exactly does Lachenmann present British audiences with so many problems? When the Belgian composer Maya Verlaak called a 2014 piece All English Music is Greensleeves, her tongue was in her cheek, but her analysis did contain a kernel of truth. From Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending to Harrison Birtwistle’s Earth Dances, English composers have excelled at evocations of landscape, but music like Lachenmann’s, which is essentially about music and how it sounds, has never been part of our national musical lexicon.

Lachenmann is not only an unashamed modernist, he is the sort of modernist whose music has no point of reference outside Austro-German tradition, so that’s two strikes against his name before any notes have actually been played. His work poses searching, sometimes uncomfortable, questions about music—how does it sound, what is it for, how should we listen? He has the temerity to suggest that music considered “beautiful” and “moving”—which might include rare pieces such as Górecki’s Symphony No. 3 and John Tavener’s The Protecting Veil that break out from the classical ghetto, and certainly all rock and pop—might not be beautiful at all, instead achieving its effect through pushing buttons that are preset to mess with listeners’ emotions.

The problem, as Lachenmann hears it, is that as soon as a sound considered “beautiful” establishes itself as part of the compositional lingua franca, that’s the very moment its effectiveness fades; it becomes an effect, a too-easily-achieved emotional hook, rather than something genuinely beautiful rooted in sound. Lachenmann’s response is to shred accepted ideals of instrumental technique. A soaring melody on a violin communicates as being “beautiful” because listeners have been conditioned by the expectations of “good technique”. But what, Lachenmann asks, could happen if fingers trained to touch a string at a particular angle moved even a couple of millimetres to the left or right? What sounds lie secreted in the cracks?

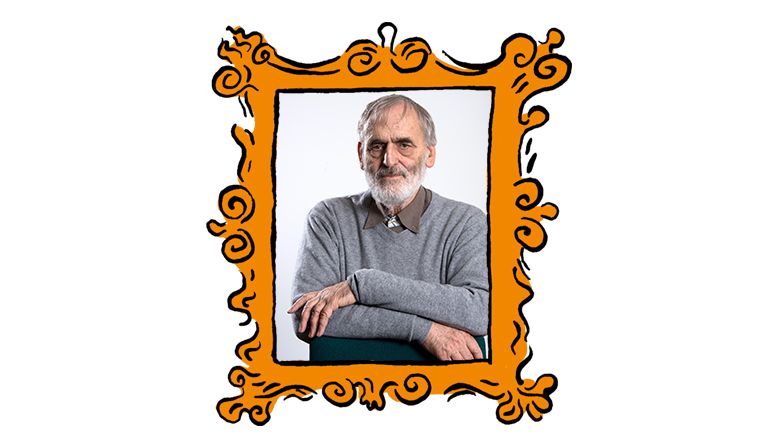

If this makes Lachenmann sound like a moralising bore who gets off on denying people the simple pleasure of the music they love, nothing could be further from the truth. When I interviewed him for The Wire magazine back in 2003, I found a man of infectious good humour, but one determined never to sell his idea of music short. Calling his piece My Melodies was at the same time a massive provocation, a joke, and also a call to action. Embedded inside its structure is a Beckettian sense of waiting for melodies that can never quite arrive. A chordal pattern or a hint of an arpeggio feels like it might be about to blossom into melody, but the music has already moved on.

His decision to construct My Melodies around eight French horn players, who sit in a semicircle in front of the conductor, was no coincidence. From Beethoven through to Schumann, Mahler and Bruckner, the French horn, blasting triumphant motifs into the hall, lay at the core of late classical and romantic orchestration. Lachenmann’s writing for horns is, instead, often a thing of finespun delicacy. He asks the players to take apart the tubing of their instruments and blow across the top, to create ethereal humming, rather like when you do likewise over a milk bottle. Lachemann’s music repositions the notion of playing an instrument to incorporate the possibility of playing with instruments.

And also with our expectations. Volkov often appeared to be conducting at fast tempi, but what we actually heard was music fading towards near stasis, the only “speed” being the sound of music hurriedly rubbing itself out, trying desperately hard not to be there.

This sort of musical psychodrama doesn’t sit easily in a country where larks ascend and modernist composition has always been held at the margins. But Lachenmann, I say, is a taste worth acquiring. The sheer sound of the thing is overwhelming, as one marvels at his powers of invention. My Melodies reaches its endpoint as melodies that were never there anyway have evaporated into the ether, leaving the musicians inhaling and exhaling deep and serene breaths. The music has gone—how do we start over again?

Why don’t Brits get along with Germany’s greatest living composer?

The sort of music pursued by Helmut Lachenmann—music about music itself—has never been among our enthusiasms

December 05, 2024