Search for “bog” in this new edition of Seamus Heaney’s poems and you will find the word some 60 times; the 1,200 tissue-thin pages are mulchy with “the squelch and slap of soggy peat”. There is the one in Northern Ireland that features in the celebrated “Digging”: “My grandfather cut more turf in a day / Than any other man on Toner’s bog.” And there is the bog in Jutland that Heaney visited in 1973 and where he finally laid eyes on the Tollund Man, the Iron Age human corpse preserved in the acid of Danish peat, which he had already preserved in the alkali of verse.

The second poem in the book, “October Thought”, was published in Q magazine in 1959 under the pseudonym “Incertus”; in it, a swallow returns to its nest, “flitting the roof of black-oak, bog-sod and rods of willow”. The line is echoed, 47 years later, in a second “Tollund Man” poem, with its “bunch of Tollund rushes – roots and all – bagged in their own bog-damp”. That pseudonym was a witty misnomer. “Incertus”, meaning “not sure of himself”, was the choice of one calmly certain of his own direction and abilities, of what would have to be waded, from bog-sod to bog-damp.

“Digging” is a picture of his father digging potatoes, to feed a little life with dried tubers: “Between my finger and my thumb / The squat pen rests. / I’ll dig with it.” It was placed first in every selection in which it was included, and on it many a student will have written essays (“How does Heaney contrast the imagery of his father’s digging with his own poetic ambitions?”). Heaney’s was a conception of poetry as archaeological dig—the excavation and discovery of old life. But those who dig can be sowing new life, or burying for safekeeping and preservation, or even, as a dog will, for the sheer joy and flurry of it.

Gathering his work into a single volume affords readers the luxury of tracing words and leitmotifs across Heaney’s half-century career. In 1964’s “Easter Son”, a baby is born “under drifts of sheet and counterpane”; in “Aubade” (1966) the speaker lies beneath “the drift of white linen”, a line that returns in 1982. One echo sounds at the almost-last poem from the almost-first. “Easter Son” was published in 1964: “suddenly a son has burst, all chestnut-ripe, into her bed / To rivet – or to wedge between – their love.” And in July 2013, six weeks before his death, Heaney wrote “Black Walnuts”, its 14 unrhymed lines tracing the outline of a sonnet. It describes the fall of the nuts on a barn roof in Massachusetts, the crack of their shells “like a hardwood mallet hammering a wedge into the moment, splitting it ever open”. But this late poem also describes the method of his poetry, which hammers wedges into moments and memories, splitting them open like walnuts.

Eschewing “collected” or “complete”, the editors have settled simply for The Poems of Seamus Heaney. This huge and varied book does not neaten but complicate: there is no single thread suddenly revealed, no single revelation to be gleaned by their sedulous assemblage. Here are the 12 collections, chronologically placed, including Death of a Naturalist, Field Work, District and Circle and Human Chain. These, with a 1975 pamphlet, are interspersed with some 200 poems, published in journals and magazines but hitherto uncollected in book form and much less well known. Most excitingly, and after nearly 500 pages of commentary, tucked at the back is the gift of 25 never-before-seen poems, selected by Heaney’s family from his papers. Faber, to whom Heaney was loyal all his working life, have in the 12 years since his death done him proud: this book comes hard on the heels of recent radiant volumes of letters and of translations (where readers will find book-length treasures such as Beowulf or The Burial at Thebes, not included here).

The editorial trio is tireless. Or is it a duet and guest-star? “Rosie Lavan and Bernard O’Donoghue with Matthew Hollis” is a credit worthy of a Hollywood cameo and intriguingly masks the division of labour. Their commentary occasionally nudges towards the student revision guide—“military metaphors run throughout the poem”—and they rap Heaney over the knuckles for his “sexist imagery” in a line that contains nothing of the kind. But theirs is a feat of scholarly diligence and patient explanation, tirelessly helping the reader develop an eye and ear for Heaney’s words.

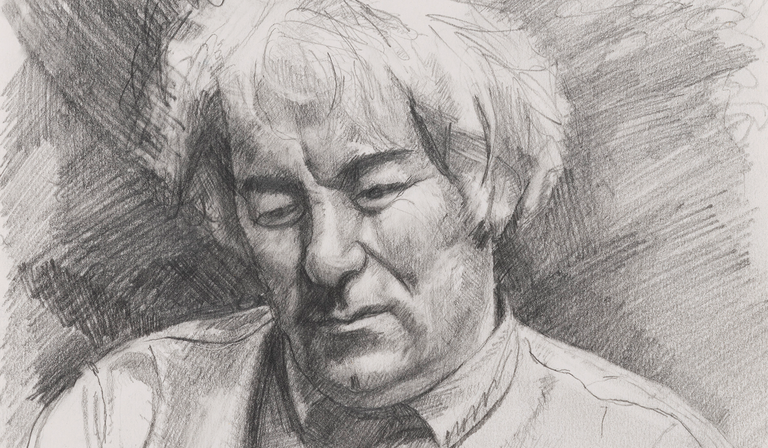

Heaney’s legacy was secure without such efforts, which makes them even more commendable. Heaney uniquely combined critical praise with commercial success. The crowning accolade of the Nobel prize in literature went hand-in-hand with profiles in Vanity Fair and, at the final count, seven-figure sales; his verse found its way into GCSE papers and presidential speeches. His name rhymed irresistibly with “famous”, a celebrity that led to a schedule he found hard to endure. His every word was scrutinised, and each could bear the scrutiny. Minutes before he died, he sent a text to his wife, Marie: “Noli timere” (“Don’t be afraid”). As last words go, they were perfect—and made news stories around the world.

Heaney’s popularity and subject matter—the sheer ease with which his poems can be enjoyed, although they are far from easy—have occasionally cosied his reputation. (One of his early critics, arguing that he had sunk into the tedious soil of landscape painting, received a wonderfully witty and rude rhyming retaliation.) There is so much here that is beautiful, poetry of pearl and mother-of-pearl and peacocks, of moondust and moonglow; even tarmac sparkles, as he drives down a “dewy motorway”. But there are other kinds of bogs in Heaney, too, which can be offered in retort to anyone who thought him a purveyor only of nacreous delicacy or Oirish pastoral.

Witness “Boy Driving His Father to Confession”: “you made a man of me / By telling me an almost smutty story / In a restaurant toilet”. That “almost” is necessary for the metre—the blank verse of Wordsworth’s The Prelude, with which Heaney’s memories of childhood often seem in duet—but is characteristically precise, as a father gropes towards conceding his son’s adulthood, spurred into almost bravery by a confined situation that precludes face-to-face dialogue: the seedy impersonality and curious intimacy of peeing together against a wall.

In “Wedding Day”, a similar visit is paid: “When I went to the gents / There was a skewered heart / And a legend of love.” Again, precision, not least in the perfect register of “gents” (that curiously dated phrase, a euphemistic twist of posh and common, formal and informal). Cupid’s arrow soars out of Greek myth to skewer a heart graffitied on the wall of a public lavatory.

There is another visit to the gents in a prose-poem featuring “meal-sacks nailed across birch poles, whitewashed GENTS and LADIES”; or there is an encounter, originally titled “The Gents”, with “Loyalists in the Gents of a Belfast Hotel”: “That’s what three women could never do – piss in the same po!” In the gents, men are rarely gentle. Even Robert Lowell, who called Heaney “the most important Irish poet since Yeats”, is encountered in the bogs:

We made our pit stop about half a mile

From the demesne gates, pissing like men

Together and apart against the wall.

[…]

As shoulder to shoulder, before we got back in

He intimated he’d probably not be

Returning to Caroline.

“Pissing like men”; “that’s what three women could never do”; “[my father] made a man of me”: here against the urinals is a quiet interrogation of what men are, or feel they ought to be. These poems can be as acrid as they are sweet, musty with the ammonial smell of the gents, the “catspiss smell” of currant leaves crushed between the fingers.

In the most autobiographical verses, “I” and “he” dance an uneasy pas de deux. Heaney writes from within and sees himself from without: “I rhyme / To see myself, to set the darkness echoing.” The echo here is of Tennyson (“set the wild echoes flying”), but the pleasure of this book lies in Heaney’s own echoing words. Rot, root, skull, bone, dust, bog, sod, dung: these would have long entries in a Heaney concordance, and are the means by which he threw off a starry-eyed devotion to Gerard Manley Hopkins and discovered the lyrical leanness that distinguishes his own voice. In “At a Potato Digging”, he alights on “Flint-white”, disdaining the tum-ti-tum lilt of “as white as flint”. “Blackberry-Picking” is made of 207 words, of which 173 are monosyllables.

This voice found a wide public via the 34 poems collected in Death of a Naturalist, which appeared to huge acclaim in 1966, the same year as Basil Bunting’s Briggflatts, a long poem with some of the same lyrical dry rot (Bunting: “In the grave’s slot / he lies. We rot. […] Their becks ring on limestone / Whisper to peat.”). For while the influence of Yeats, say, is obvious, it is with the poets of northern England that, to me, the sound of Heaney often belongs: with Bunting’s granular masonry or (the recently deceased) Tony Harrison’s Saxon-ese rendering of the Oresteia. The latter seems a clear influence on Heaney’s spitting portrait of the prophetess Cassandra, raped in the ruins of Troy. Words are snapped in two like twigs, or bodies, the stanzas rent, laid out in shards as on a battlefield:

Her soiled vest,

her little breasts,

her clipped, devast-

ated, scabbed

punk head,

the char-eyed

famine-gawk –

she looked

camp-fucked

and simple.

[…]

Little rent

cunt of their guilt.

Heaney’s disturbed soil can be strewn with the “tattered meat” of broken bodies and broken words. In even his earliest poems, the vocabulary of rot and slime accumulates on the spade. Digging, the poet will get blood and mud under his fingernails. Neither childhood nor Ireland, for Heaney, was an idyll. Kittens drown, or are drowned, rather, “soft paws scraping like mad”. Even the milk smells sour. “Hope rotted like a marrow.” “Live skulls […] wolfed the blighted root and died.” Nature is not always a friend, and Heaney’s landscapes are not always rhapsodic: sea spray “spits like a tame cat turned savage”; rocky promontories are bone splintering through flesh. As in some inverted ode “To Autumn”, the blackberries picked each year by his infant hands—initially a fruity, Keatsian evocation of “thickened wine”—turn furry and ferment, “rat-grey” and stinking of rot. “Each year I hoped they’d keep, knew they would not.”

Even when young, he was unusually attuned to death and decay: at 25, he watched his expanding waistline put a “heavy stress on mortality”. But the rotting, of blackberries and of men, is pitched triumphantly against preservation, whether in the bogs of Jutland or a collected edition of verse. More than once, he quotes Eliot’s line of fragments shored against the ruins, placing faith in a “poem that will endure”. A biblical shower of hailstones leads him to make “a small hard ball of burning water running from my hand / Just as I make this now out of the melt of the real thing.”

Making lasting poetry from something as simple as an evanescent pellet of frozen rain may be what the Nobel citation described as Heaney’s exalting of everyday miracles. But that doesn’t seem quite accurate. Is it that he sees miracles where the rest of us see mundanity, practising the transfiguration of the commonplace? Certainly, he can imbue the quotidian with the mythic. (For Heaney, in the tunnels of the Underground, the Circle line becomes an evocation of Dante’s circular hell; elsewhere, a seal appears as an “ocean god”.) But it was Craig Raine who had it right in saying, simply, “he can describe things”—which is the highest praise and most accurate summation. Heaney would have agreed, recalling the epiphanic advice from a fellow writer: “Description is revelation!” It is not the hailstone that is the miracle, but his ability to describe it—to build what will last out of what will melt, through the act of alighting, as he does again and again, on the right words. He sees what will melt, makes what will endure.

“Mid-Term Break”, Heaney’s most popular poem, is an account of his brother’s death in a car accident, and of the corpse being laid out: “a four foot box, a foot for every year”. It is full of immortal phrases that embalm memory (his mother’s “angry tearless sighs”, the “poppy bruise” on the body). Again, numerous classroom essays will have been written about the opening:

I sat all morning in the college sick bay

Counting bells knelling classes to a close.

At two o’clock our neighbours drove me home.

In the porch I met my father crying …

Yes, alliteration; yes, internal rhyme; but what moves me is the rightness of “met my father”, instead of “found” or “saw”, for this is a solemn meeting of a new man, transfigured by grief. “Crying” drifts, syntactically untethered, applicable both to the speaker and his father, their tears intermingled.

It is irresistible and reductive to read this volume as biography, charting the development of a poet and his life, through the political, the amorous, the romantic (the love poems have been called the best since Hardy’s). The small boy meeting his father in the porch on p32 looks, strap-hanging, into the mirror of a Tube-train window on p601 and sees “My father’s glazed face in my own”. The poems of the last collection, Human Chain, were written after a stroke and are imbued with a sorrowing hope, a concern with last words and words that last. As a little boy, he watched his father digging, hoping to dig with his “squat pen”; as an old man, he is gifted a fountain pen, from and with which he formed a poem:

Now that your pen is in my hand

And I have fears

That poems may cease,

[...]

… I dip and fill

And start again, doubts

Or no doubts, let flow.

The allusion to Keats (“When I have fears that I may cease to be…”) was originally more marked. But from his third line Heaney cut “to be” for, he said, “whether I write or not, poems will not cease to be”.

Lowell, Heaney believed, had no need to offer Charon an “obol”, the coin placed on the eyes of the dead to pay for safe passage across the Styx; the ferryman had been “paid in the coin of language”. So it was for Heaney, who went out into the world and departed from it “with words imposing on my tongue like obols”. Noli timere.