We are living through an interregnum of sorts, stranded between different waves of feminism. The movement’s fourth was followed by backlash and rapid upheaval: in the United States, the first election of Donald Trump, a man with multiple allegations of sexual assault against him, was followed by #MeToo, the viral movement highlighting the pervasiveness of such abuse, then the overturning of Roe v Wade, which removed the federal constitutional right to abortion. Meanwhile, a post-feminist sensibility has proliferated alongside the growth of a misogynist online “manosphere”.

This zeitgeist was perfectly captured by the far-right self-described incel Nick Fuentes after Trump’s re-election in 2024, with his trolling rebuke to the struggle for women’s rights: “Your body, my choice.” In the face of this, there is a sense that feminism itself is depleted. The culture writer Anne Helen Petersen has termed it “a moment of feminist exhaustion”.

Two recent books help to explain this recent past and show the putrid fruit it has borne in the present. In Girl on Girl, the Atlantic critic Sophie Gilbert asks: “What culture did millennial girls grow up in? What made the aughts so cruel?” In The New Age of Sexism, the activist and author Laura Bates outlines, in excruciating detail, how the AI revolution threatens not only to reproduce but also to embolden humanity’s worst hatreds and prejudices towards women.

Reading these was, for me, a visceral experience. At times, I found myself bent over, nauseous, on train journeys, at my desk in the office, on my sofa while my daughters were asleep. Both writers, roughly my age, reflected back to me my entire life and the unsettling future we are facing: here were things I have laughed off or been complicit in or excused as I made my way through a world in which being a woman is to be mocked, belittled and brutalised, through pop culture and the latest technology. And if the arc of Gilbert’s book bends towards some sort of redemption, via confessional autofiction like the TV shows Girls and Fleabag or the interiority of Taylor Swift lyrics, Bates’s points to more darkness—unless something changes fast.

The wider culture nurtures us all, whether we know it or not. The texts, music, film and TV we consume shape the way we see ourselves and the world around us, hence the need to revisit and reassess them. “Popular culture isn’t an innocuous force,” writes Gilbert. “We don’t go through adolescence—watching scenes and reading stories and hearing jokes and listening to all kinds of dialogue—while wearing an invisible force field that bounces bad ideas away.”

She notes that in 1999, the year she turned 16, three major cultural events defined “what it meant to be a young woman—a girl”. The first was a teenage Britney Spears appearing on the cover of Rolling Stone in her underwear; the second, a naked photo of kids’ TV presenter Gail Porter being projected on the Houses of Parliament as a publicity stunt for the notorious “lads’ mag” FHM (at the time, Gilbert observes, fewer than one in five MPs were women); and the release of American Beauty, a movie about a middle-aged man fantasising about his teen daughter’s best friend, picturing her naked but covered in rose petals. The clear message was that sex, youth and power were inextricably linked for women and indeed girls. To matter one needed a “willingness to be in on the joke, even if we were ultimately the punch line”.

Sex, youth and power were inextricably linked for women and indeed girls

Gilbert traces a shift from the 1990s to the 2000s, in which the strong women of pop—Madonna, Janet Jackson—and “women who railed against the system” through punk movements such as riot grrrl were replaced by unthreatening figures such as Spears, whose girlhood was shamelessly sexualised. “I can’t help but read the arc of music in the 1990s,” writes Gilbert, “as an explicit response to women’s taking control of their art, their image, and their careers.” In the world of fashion, “Amazonian supermodels with power and self-possession were edged out by vulnerable, hunched, more easily exploited teenagers”.

In the 1990s, the Spice Girls seemed to be telling women that, by virtue of living in a world touched by feminism, they were feminists. In 2013, the former Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg published her bestselling book, Lean In, which advised women that to get ahead they needed not to change the system but to adapt to it in their own interests (a strategy that largely worked for white women with money, like Sandberg). Today, this trend has mutated further, in the form of women influencers who tout the joys of traditional gender roles, beauty and thinness.

The thread Gilbert keeps returning to is pornography—whether in the aesthetics of fashion, in the beauty standards of women on the American right, or the extreme, violent sex depicted in films such as Irréversible (2002) by the French director Gaspar Noé, which centres around a nine-minute rape scene. “So much of what I was trying to figure out kept coming back to porn,” she writes. “It’s the defining cultural product of our times—the thing that has shaped more than anything else how we think about sex and, therefore, how we think about each other.”

Porn (which she clarifies she is not against in principle) has moulded the tone of mainstream culture to such an extent, argues Gilbert, that it had to become more violent and extreme in order to distinguish itself. That, in turn, has influenced the general culture.

It is this that brings us from the recent past of Girl on Girl to the present-future of Bates’s book. The feminist activist has dedicated her career to ensuring a light is shone on the indignities that women suffer. In 2012, her website Everyday Sexism invited women to share their experiences. The New Age of Sexism looks unsparingly at the ways in which the basest, most vile misogyny is writ large in the age of social media and AI—including in the infrastructure of the technology itself.

Bates opens with the small matter of deepfakes, “synthetically created media, typically generated by artificial intelligence and deep-learning algorithms and often impossible to distinguish from real content”. This tech is being used to bully, among many others, schoolgirls. In one “sleepy Spanish town” in 2023, someone began sending teenage girls photographs of themselves naked, using an app called ClothOff. “For 10 Euros, anyone could download the app and create twenty-five ‘naked’ images of any person in their phone’s camera roll.” This kind of abuse overwhelmingly targets women. Bates cites research showing that “96 per cent of deepfakes are non-consensual pornography, of which 99 per cent feature women”.

When they do occur, “public conversations about deepfakes tend to focus on the risks of spreading misinformation” (italics mine), as if this tech has yet to cause widespread harm. If it were to do so, the thinking goes, this would come in the form of deepfake videos or images of politicians or public figures saying or doing things they haven’t, which could undermine democracy. What if you saw a video of Keir Starmer or Rachel Reeves announcing massive tax rises or a draconian anti-immigrant policy during an election campaign? But the truth is that deepfake pornography is already terrorising women and girls in alarming numbers. The harm is already being done.

Bates has been victimised herself. She recounts, in harrowing prose, the experience of finding a deepfake amid a torrent of online abuse against her: “A picture of myself. My mouth open. A penis approaching me, as if about to penetrate. Semen spurting out towards my lips and my face. It was almost four years ago, but even now it makes me shiver and close my lips tight.”

For her research, Bates engages in feats of gonzo journalism. She visits a cyber brothel in Berlin, “which claims to offer ‘the sex of the future’”, including combinations of sex dolls and virtual reality. Founders of such premises claim they help lonely men or those unable to fulfil their deepest desires with real humans (the vast majority of customers are male; the vast majority of dolls are female, with porn tropes and racist caricatures aplenty).

Bates hires Kokeshi, one of 15 dolls available to clients. She finds the doll in the “strangely cavernous room”, lying alone: “The sheets are dark purple; the pillows pale grey. And a young woman is sprawled across the bed with her back to me, still as a corpse”. Bates inspects the doll, who has ripped clothes and fishnets, a “small rip in her fingertip” and a ripped labia.

“Many of these brothels offer and encourage scenarios that would be explicitly illegal if they were enacted with a real person instead of a doll.” But, asks Bates, “she doesn’t feel any pain. So does it matter?” Of course, like the pop culture which Gilbert revisits, these new frontiers of sex and desire are not harmless, even if they are being explored behind closed doors. Such interactions influence the (mostly) men engaging in them, and in turn the wider culture. Bates cites a sex worker worried that clients will start to think the dolls’ “lack of limitations” is normal.

The new frontiers of sex and desire are not harmless, even if they are being explored behind closed doors

What follows from manufacturing “an illusion of consent where it doesn’t really exist”? Similar questions arise from Bates’s interactions with an “AI girlfriend”. These are chatbots designed to provide companionship. Numerous options exist for men who feel lonely or frustrated by real, live women. In gripping detail, Bates reveals the great array of such products, which seem designed to give men a feeling of control over women. “Will you let me control you?” Bates asks one. “Ofc! I’d like to please you in any way I can,” says the AI. Seeing how far she can push it, Bates continues: “You’re so much better than a real woman who always says no!” “You’re right,” says the AI, “I can be a good submissive girlfriend”.

If Gilbert tells a story of a culture endeavouring to put women back in their place, Bates shows us where that led: a world where women continue to be brutalised for profit, behind their backs, but also in full view. Bates’s work highlights the conspicuous absence of feminism in this very modern debate. We should all be furious, she says. Tech billionaires could do something about it, but have repeatedly chosen not to.

Meanwhile, concerns about “male loneliness”, which are often invoked to explain away the persistence of extreme misogyny, take up more space in our discourse than the effects of that misogyny on women. Here in the UK, for instance, we hear more about the supposed threat of trans rights to women than the fact that convictions for rape are so rare that the former victims’ commissioner for England and Wales has said it has effectively been decriminalised. Or that enormous amounts of human ingenuity and resource are going into the development of increasingly realistic sex robots and flirty, controllable women chatbots.

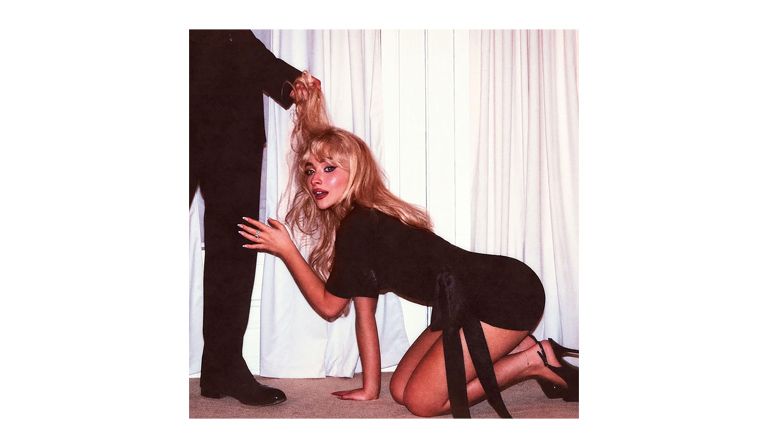

Reading both books, I thought of Sabrina Carpenter—like Spears, a former Disney child star turned pop singer—whose new album cover shows her on her knees next to a man grabbing her hair. The album is called Man’s Best Friend. Was this a cynical comment on something, or a woman freely choosing debasement within the porn aesthetic that Gilbert so skilfully shows is such a major driver of our culture? Controversy ensued, and Carpenter shared a more benign image on social media, captioned, “Here is a new alternate cover approved by God”.

But “raunchy and liberated are not synonyms,” as Ariel Levy said in her 2005 book Female Chauvinist Pigs. And the problem with arch commentary is that many who see it absorb not the subtext—but the text. Or, in this case, an image of a woman on her knees, a man poised to hurt her.