In the last 100 years of American history, four avowedly progressive presidents came to power in circumstances that offered a serious opportunity to shake things up to the advantage of their poorer fellows.

By any measure, the first two succeeded. Franklin Roosevelt rode to the rescue of unemployed individuals and dustbowl regions, and legitimised unions for previously atomised workers. Lyndon Johnson secured Medicare for the elderly, food stamps for the poor and, above all, civil rights for African Americans.

Judged against these standards, the second presidential pair failed. Bill Clinton and Barack Obama both increased the minimum wage a bit, but neither restored its real value to where Johnson had left it decades before. Neither got a grip on poverty—indeed, the holes Clinton ripped in the safety net, in the name of “welfare reform”, deepened the human emergency that would confront Obama after the banking crisis.

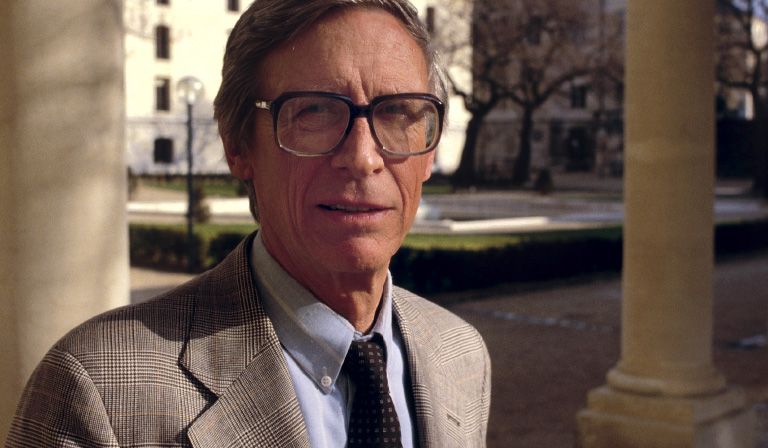

Exactly midway through this American century—its first half defined by an advance of economic justice, its second by regression—the Republic’s greatest political thinker, John Rawls, produced his philosophical framework for the good society. The most distinctive feature of A Theory of Justice (1971) was an obligation to ensure that things were arranged as well as possible for those who had least.

Clinton and Obama had read Rawls closely. Obama was a graduate student at Harvard when Rawls was a big presence there, and specific phrases in his speeches have been identified as reworked Rawlsian propositions. In 1999, Clinton honoured Rawls with a National Humanities Medal, recalling how he and Hillary had been “moved” by A Theory of Justice in their youth, hailing its “argument that a society in which the most fortunate help the least fortunate is not only a moral society, but a logical one.”

Chronology precluded Roosevelt or Johnson from reading the book but, even if they’d had the chance, neither would have bothered. LBJ was a schemer driven by a lust for power, who thought and spoke in earthy terms about aligning interests to get things done. FDR was a mercurial opportunist with scant patience for even the urgent (and relatively worldly) theorising of his contemporary John Maynard Keynes. Rawlsian abstractions wouldn’t have woken him up to, say, the New Deal’s moral failing on race; they would have left him cold.

Such reflections nagged at me when I first opened Daniel Chandler’s Free and Equal, a crash course on Rawls bolted together with an agenda for contemporary Britain inspired by his work. I couldn’t help wondering: what if Rawls’s practical role in his own time was less as a cartographer—politicians abandoned his map once they found advantage in changing course—and more as a brilliant rationaliser of the fairer direction in which the postwar US still seemed to be edging? Does this doom hopes of using him to reboot our own politics today?

But there’s no doubt that Chandler, a philosopher-economist at the London School of Economics, is answering a yearning for something. His book has attracted the most unlikely range of ringing endorsements—from former archbishop Rowan Williams to Matt Lucas of Little Britain fame. Thinktanks have been falling over each other to host events, the FT ran a full-page interview with the author, and he got a slot at the recent Progressive Britain conference, a get-together of the Labour right headlined by Keir Starmer. There is, however, nothing factional about Chandler: he has been welcomed onto (and sounded equally at home on) podcasts with the staunchly socialist Owen Jones and the punchily centrist James O’Brien.

But could he persuade a Doubting Thomas like me to share in his hope that 21st-century deliverance can come courtesy of one great 20th-century mind?

The first 100 pages of the book are a crisp exposition of Rawls’s principles, no small feat given their range, rigour and many ambiguities. There is potential confusion even on the number of basic Rawlsian rules, which can be as few as two (covering basic liberties and allowable inequalities) or as many as five (if we add in sustainability, basic material needs and then split that “allowable inequalities” test into its “equal opportunities” and famous “doing best by the worst-off” dimensions). We’re ably guided through these thickets and emerge with a clear understanding of how the theory fits together, and its distinct place in the history of ideas.

Chandler does a great job of rescuing Rawls from his caricature as—to borrow Nye Bevan’s barb against Hugh Gaitskell—a desiccated calculating machine. The Rawls that emerges here is at least as concerned with dignity and power as the schedule of marginal tax rates. The insistence that the just economy is that which does best by the worst-off flows not from bleeding-heart paternalism, but almost the opposite: taking the individual so seriously that the only valid social contract is something every one of us, down to those at the bottom, would freely sign.

However, precisely because Chandler invites us to reckon with a richer rather than a reductive Rawls, the theory becomes a hazy practical guide, tricky to operationalise. We learn that Rawls talked vaguely about the bottom half of all earners being the “most disadvantaged”, so who, exactly, are we to put first? Given his special focus on paid work, how are we to factor in the claims of the unemployed, carers and workless disabled people, who are often the poorest of all? After we’ve clocked that Rawls wants to prioritise not the incomes of the disadvantaged but the fuzzier and less-measurable goal of their “life chances”, how can we expect his tests to settle thorny policy dilemmas?

It’s only because the book sets out the ideas so vividly that these snares are so easy to notice. Indeed, Chandler tests various weak spots himself. The criticisms Rawls faced in his day, from both the libertarian right and the Marxist left, are aired and pretty effectively dispatched. So, too, is the attack from the communitarians. Blinded by the liberal individualism of Rawls’s basic methods, they missed his painstaking insistence on allowing community groups, churches and families to settle their own rules in private.

Less space, however, is given to the challenges posed to the theory by the evolution of life and thought over the half-century since it was written. Thanks to feminism, it’s no longer plausible for politics to discount the household as a black box, and the informal rules of life within as none of its business. Many of the most vibrant campaigns of recent times—think of the drives to decolonise museums or to secure reparations for slavery—are concerned with redressing historic injustices, challenging the Rawlsian endeavour of writing the rules of fairness on a blank sheet. And in a world interconnected by trade, migration and shared environmental dangers, Rawls’s fixation on a national social contract is surely liable to provide fewer answers.

Then there is politics. If the era of Trump and Brexit taught us anything, it is that many voters are inspired by emotions that left-wing liberals struggle to understand. The American psychologist and centrist writer Jonathan Haidt has suggested that the mainstream left has a monochrome morality, overwhelmingly defined by “care” and “fairness” (which it then further reduces to equality). By contrast, the right-wing mind is Technicolor, featuring such additional values as respect for “authority” and the “sanctity” of certain customs and symbols.

To be fair, Rawls (and Chandler) are committed pluralists, favouring ground rules that protect people with values that they themselves don’t share. But while “I defend to the death your right to say it” is a good frame of mind for drafting constitutions, such earnest Rawlsian detachment rarely withstands the cut and thrust of competitive politics.

Keir Starmer, the one person Chandler says he’d most like to read his book, is a case in point. The civil liberties lawyer who stood with the McLibel two might once have looked like a potential Rawlsian ruler. Today, he acquiesces in draconian protest laws, slurs Rishi Sunak as soft on paedophiles—and is streets ahead in the polls. He offered a rare financial commitment recently, pledging to freeze council tax, even though the very poorest typically get a rebate on that bill. The electoral imperative isn’t those with nothing at all, but the “squeezed middle”.

As I read through Chandler’s practical proposals, I was struck by just how many of them I had previously endorsed in writing—during my time penning Guardian editorials. Taxing wealth; protecting public liberties in a way that doesn’t trample on conservative consciences; tackling private school privileges… I wondered if we’d have achieved any more for these causes if we’d known that Rawls’s theories provided additional grounds for supporting them.

On a few occasions, the swerve from some education policy or devolution reform back towards a Rawlsian axiom brought to mind those left-wing meetings that drift from argument over the substance of the matter to trading lines of Marx and contesting what the old prophet might have thought. At other points, Rawls’s name drops away for a few pages, as when Chandler prosecutes his own claim that the British constitution’s close shave with Boris Johnson strengthens the case for writing more of it down. Chandler didn’t persuade me that his very American hero had anything much to say on that question, but it didn’t matter: I still agreed with him.

I don’t want to suggest that the greatest political thinkers—and, make no mistake, Rawls is sometimes mentioned in the same breath as Mill, Hobbes, even Plato—are no more than froth, carried along by the tide of their times. That is way too despairing. Ideas can matter in politics—if they align with interests.

As I wrote in Prospect last year (July 2022), “neoliberal” notions of hands-off business regulation and advancing the frontiers of intellectual property really did change the world, but only after monied interests were persuaded to run with them. Likewise, on the left, socialism only became a serious force to be reckoned with when intellectual societies combined with organised industrial muscle to form the Labour party. The challenge on the left must again be to weld progressive ideas to the interests they need to serve.

But how? Rawls is perhaps singularly unsuitable for this particular task: he sought to bring the great courtroom virtue of disinterestedness into the political realm. In his celebrated thought experiment, citizens imagine sitting behind a “veil of ignorance”, where they do not know anything about their own social standing, and must then navigate the requirements of justice from that position (albeit with aspects of reality incrementally let back in).

It isn’t Rawls but Chandler himself who eventually supplies a brilliant example of a field in which big ideas can evolve in harmony with recalibrated interests. His superb final chapter on industrial organisation has, tellingly, few footnotes relating to his guru. It dives down to engage with experiments involving cooperatives, co-management and reformed corporate governance; it soars up to expose the sheer arbitrariness of the Anglo-American way of business we’ve come to think of as natural. Skipping freely between gritty evidence and high theory, and grappling impressively and impatiently with practical obstacles to change (such as the difficulties new co-ops face in raising capital), Chandler here is less reminiscent of Rawls than his own one-time teacher, Amartya Sen.

The truly exciting potential here is for a new self-sustaining settlement, where more citizens acquire a slice of the power and wealth currently hoarded at the top of corporations, and then become a powerful constituency pushing for further advances. The recent row at Britain’s largest worker-owned partnership, John Lewis, whose boss floated selling a stake to private investors before being rebuked by the staff council, is telling. It illustrates the deep financial tides this reform agenda must swim against, but also just how animated workers become when defending a model that elevates their standing.

In the quest for a free and equal society, keeping a close eye on such real-world developments might be more instructive than meditations, however brilliant, from behind the veil.