How will future generations look back on us? This is the question novelist Ian McEwan explores in his new novel What We Can Know. Partly set in an imagined future in 2119, where a combination of climate change and the catastrophic impacts of global conflict mean that more than half the world’s population has been wiped out. The UK has become an archipelago, with lowland areas flooded and bandits patrolling waters around the islets.

A hundred years from now, people might envy what we have now that they don’t, McEwan suggests: better food, more wildlife, less radioactive air. Or perhaps anger is a more likely reaction, as they reflect on “the idiocy of those times, the warming they ignored and all that, their stupid wars, the animals they killed, how skin colour meant so much. On and on. The morons of long ago.”

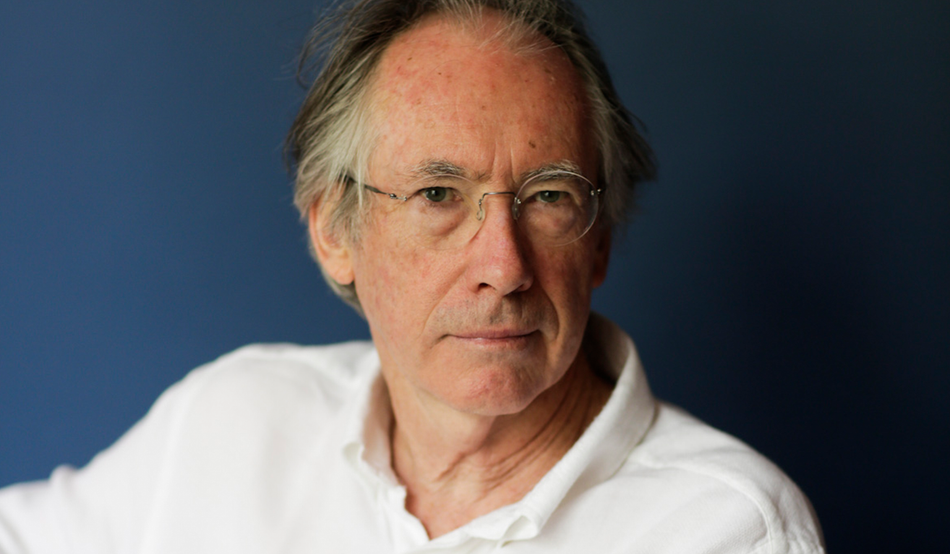

What does McEwan think? “If we manage to get through the 21st century without an exchange of nuclear weapons and if we’re on the edge of turning a corner and deflecting that rising curve of greenhouse gas emissions, we might just scrape through,” he says from his study in a converted barn in the Cotswolds, the walls lined with books. “Then, people will look back with some bewilderment on those who wish to ignore what’s clearly right in front of them. The science is clear.”

In What We Can Know Tom Metcalfe, an academic (yes, universities’ humanities departments survive in the future), digs forensically into the lives of Francis Blundy, a renowned 21st-century poet, and his inner circle. Metcalfe uses their interviews and writings, but also emails, texts and notes—their thoughts, feelings and actions unknowingly recorded for posterity in overwhelming detail. As McEwan puts it, “We have robbed the past of its privacy.”

Does he worry about future generations accessing intimate details of his own life? “I keep my emails pretty bland for that reason,” McEwan nods. “I’m not on social media, except on WhatsApp with my children and grandchildren. I’d urge caution to people who spill their hearts out non-stop on email or social media. Sooner or later, we’re going to solve a polynomial question in mathematics, which is going to break open every code we have.”

Before that open season begins, I offer him the chance to reveal if there are any skeletons in his closet. “No,” he laughs. “If I’ve got skeletons in my cupboard, they’re in my cupboard for a reason.”

McEwan considers What We Can Know to be “science fiction without the science”. “I wanted to write about the future in a speculative way,” he tells me. “People will be as alive to themselves in the future as we are to ourselves. We will be their ghosts. They will try to understand us. The ambition of the novel was to try to get the past, present and future all in one place, melding together.”

That’s no mean feat. “No, but it’s fun. Doing difficult things is one of the great pleasures in life.”

Born in Aldershot, Hampshire in 1948, McEwan has written 17 previous novels, including Enduring Love, Atonement, On Chesil Beach (all turned into films) and the Booker Prize-winning Amsterdam. “When it’s going, I love it,” he says of the writing process. “There are moments of doubt. There are times when it feels too heavy to lift. But, on the whole, I feel a wonderful sense of intellectual freedom.”

Aged 77, McEwan expects to keep writing into his early 80s, or “as long as I have my wits”. His work often engages with contemporary issues: family law, religion, anti-war protests or AI. But rather than any single concern today, he fears something more pervasive: an exhaustion that has set in as people struggle with an unending string of crises.

In What We Can Know, McEwan sums it up as a “the collapse of belief in a future, or… the fading of a belief in progress.” What does that mean for the world? “It’s almost like the air we breathe—we hardly notice it,” he says. “The moment when generations start to lose hope in the idea of a future or in the notion of human progress we face a crisis that is as big as climate change, if not bigger.”

Getting out of that existential quagmire will be difficult. McEwan believes the arts, including novels, have a role to play. “My general sense of the purpose of the novel is to reflect how we live now. We live in very, very extraordinary times. I often have this conversation with friends of my age, in our 70s or near 80s, where we ask: ‘Has it ever been worse?’ Our times seem more warlike than I ever remember…

“Even our own prime minister gave a speech saying we must prepare for war. This is astounding. If I’d heard that in the 1970s, when we were still reeling from the Second World War, I would have been amazed.”

‘What We Can Know’ is published by Jonathan Cape in hardback, eBook and audiobook.