Cricket fans of a certain age really loved Graham Thorpe, the former England batsman who died by suicide on 4th August last year. They loved him not in the transactional way you might love other highly skilled sportsmen and women who perform wonders for your team, and nor did they love him in the furtive, unacknowledged way common among Englishmen, but outwardly, avowedly. You knew this because they would say it. “I love Graham Thorpe.” You knew this too because of what happened when Thorpe made a Test hundred against South Africa at the Oval, in 2003.

Thorpe, for so long England’s best player, had spent more than a year out of the Test side following the collapse of his first marriage—which had become tabloid fodder—and a period of depression, culminating in a breakdown during a game against India in 2002. When he reached the landmark, his first for England at his county home ground, there was an extraordinary outpouring of public affection for someone who had shown themselves to be vulnerable, not in the morally uncomplicated or telegenic way now in vogue, but in the manner of a real human being, with real flaws and real virtues. Thorpe described it as the best innings he ever played.

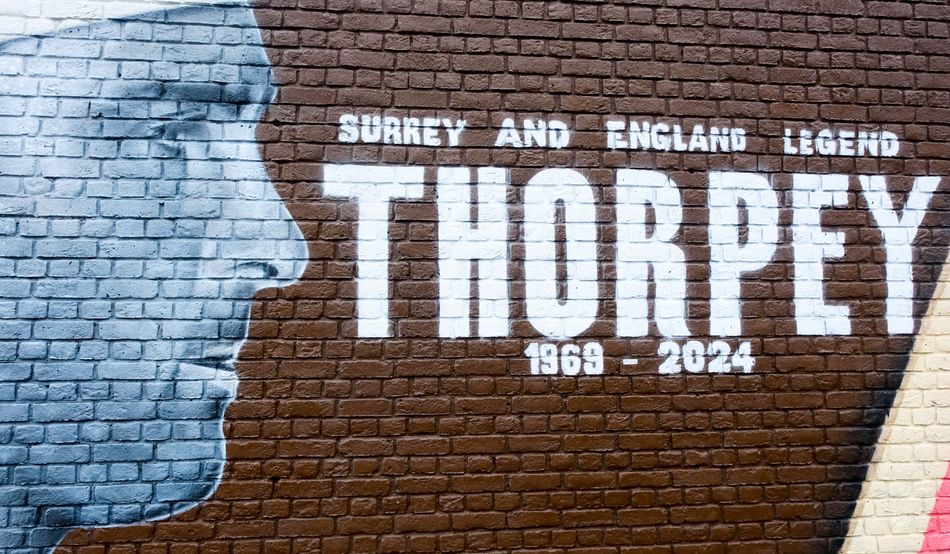

On the second day of the Oval Test this year, on what would have been his 56th birthday, Thorpe will be honoured by “A Day for Thorpey”. A sweatband—Thorpe always wore one while batting—has been designed by his family for the occasion, which, fittingly, is being held in support of the mental health charity Mind.

In an intensely demanding sport, Thorpe was a pioneer in his willingness to talk about episodes of anxiety and depression, and how his life as a professional cricketer—the long winter tours that kept him from his family in an era before broadband and video-calls, the intense scrutiny—affected his private life. When his England career began in 1993, any international player complaining about their lot was likely to be met only with reactionary sniping about stiff upper lips and the honour of representing your country. Support from within the dressing room wasn’t necessarily forthcoming either. England players at that time were contracted to their counties, not the national side, and selection was chaotic, meaning that even those as good as Thorpe weren’t secure in their place and, he said, “Not everyone in the team was always happy for you when you did well.” Nor was there much understanding of mental ill health: I have seen players of that era or before speaking with a smirk, while giving terrible after-dinner speeches at terrible end-of-season league dinners, about the classic, how-we-laughed time on tour when one of their teammates was sent “to the loony bin”.

“I’m just not a chin-up-and-get-on-with-it sort of bloke,” Thorpe told Alison Kervin in 2003, and his 2005 autobiography was a difficult read, as unsparing of himself as it was full of recrimination towards others. He described how, after his divorce, he was “living alone in our family home behind these permanently drawn curtains. I remember waking up one morning and seeing this mess in our front room—an empty bottle of Scotch, dirty plates, a mountain of fags.” Later he said: “All the skeletons in the cupboard came out, and there were a few there. As things became public it was tough and I was hurt, I was drinking lots and I was insular, bitter and lonely.”

For all that tendency to introspection, teammates said that Thorpe would be the one to notice if they themselves were struggling. His friend and former captain Nasser Hussain said: “He was always there for me in my darkest moments. And that’s probably what I feel the saddest about now, that I wasn’t there for him right at the end in his darkest moments. When you doubt yourself as a player or as a captain, you used to walk in his room and he used to put everything into perspective.” By the time his England career ended in 2005—as part of a much happier and more successful England squad—teammates such as Stephen Harmison and Marcus Trescothick could speak openly about similar problems and be applauded for it. This is a trend that has continued since, from Jonathan Trott and Sarah Taylor up to the current England captain, Ben Stokes. They all owe Thorpe a debt of gratitude.

If it is true that sport doesn’t make character but reveals it, then that cliché applies as much to the people who watch it as those who play. Following a team is in many ways a silly pastime that inspires silly, childish feelings all the more intense for being centred on a mere game: loathing of the opposition, the screaming id inside that thinks your side should always win, coping mechanisms for defeat—fatalism, black humour, anger, scapegoating, denial—and a vicarious, second-hand happiness when they do win. Sports fandom is a strange and frequently unrewarding pursuit, made normal only by its ubiquity.

Part of why Thorpe was so beloved, and why he mattered so much to those who never knew him, is that he was not an all-conquering hero, a Messi or a Ronaldo, but a plausible one. For while England in the Nineties had a core of very good players that might have won more if they had been better managed and supported, the truth was that most of the time they were outgunned: other sides had stellar, world-class players, especially bowlers. Being an England Test batsman in that time was, to channel Deadwood’s Al Swearengen, one vile task after another: the all-conquering Australian side meant Shane Warne, Glenn McGrath and a snapping, snarling chorus of close fielders. The West Indies still had Courtney Walsh and Curtly Ambrose. Pakistan meant Waqar Younis and Wasim Akram trying to rearrange the bones of your feet into a 1,000+-piece jigsaw puzzle. South Africa meant Allan Donald—murderous glare, murderously quick—and Shaun Pollock, the bowler Thorpe said often gave him the most trouble. Sri Lanka, scene of arguably Thorpe’s greatest performance, meant extreme heat and Muttiah Muralitharan, who dismissed more batsmen than any of the above.

Watching sport is also as much an exercise in projection as it is identification. The way Thorpe performed in a modest side reflected how many of us would like to think we would play a difficult hand. He was brave, stoic and skilful, but not so stoic that anyone could doubt precisely how hard it was for him, marching into the thick of yet another England batting calamity with a middle-distance stare and a slightly hangdog bearing of “here we go again”. He showed it mattered, but also that how you faced up was as important as whether you won or, more likely, lost. To watch him was to be dragged into a better, more resonant daydream—the sort that allows us to make a proper bargain with reality.

His struggles show even the most ignorant among us, those of us that needed telling, that mental illness is absolutely nothing to do with fortitude. As his wife Amanda has said, “Graham was renowned as someone who was very mentally strong on the field and he was in good physical health. But mental illness is a real disease and can affect anyone.” Because it is impossible to imagine how a person held in such high regard could arrive at a place where they thought the world, and their loved ones, would be (in her words again) “better off without him”. And it is all the more sad for learning that many of the problems that clouded Thorpe’s playing career—life on tour, work insecurity, unwelcome media attention—played a part in his decline, as did, the coroner found, possible failings in his care.

But it is also true to say that the sport he played, and many of those who watched him—who never knew him, and never spoke to him—are better in all sorts of ways because of him. That is why he was so popular, and why he won’t be forgotten.

If you’ve been affected by the issues in this piece, please ask for help. You can call the Samaritans for free on 116 123, email them at jo@samaritans.org, or visit www.samaritans.org to find your nearest branch.