Royal sources, even off the record, are usually quite bland. They are guiding hands for a journalist trying to shape a story, vanilla quotes which spout the monarchy’s view. Occasionally, though, a royal source gives their own view. Earlier this year one impeccable source at the heart of the royal family told me their biggest fear. “Charles’s accession,” he said, “could be the greatest threat to the British monarchy since the abdication.” Why so? He continued: “There’s a great danger he will make it all about him. He needs to play it very carefully. He’s capable of getting it right, but also of getting it drastically wrong.”

That opinion, proffered in a quiet but brutally honest aside, is more widely held within royal circles than you might think. Senior courtiers and high-ranking Whitehall mandarins privately share the fear that the Prince of Wales could morph into a meddling, dangerous monarch. An opinionated king, who can’t stop interfering in the issues of the day under the pretext of “wanting to make a difference.” One who wants to remould the role from a stately, silent figurehead decked out in fancy uniform to that of a far more pro-active sovereign—potentially threatening the whole constitutional basis and future of the monarchy itself.

For many in Britain, King Charles III—and despite past reports he may reign as George VII, Charles III is almost certainly what it will be—still seems a distant prospect. The Queen, now 91, shows little sign of frailty, even as her husband retires from public life. Yet for those grey men—and, yes, it is still mainly men—who silently operate in Whitehall’s shadows, the historic transition is one they have secretly discussed for decades.

Indeed, the plans for the Queen’s death and Charles’s accession are rehearsed down to the last detail, filed under the codename “London Bridge.” Charles, who will become king at the moment his beloved mother breathes her last, will address the nation within hours of her death. This represents the first departure from what happened on the death of George VI in 1952; the young Elizabeth, on tour in Kenya, returned wearing black but said nothing, starting out her reign—perhaps—as she meant to continue. But it is another age now, and Charles is a very different personality. He will “set out his stall” to parliament, heads of Commonwealth, foreign heads of state and religious leaders in what is, effectively, his regal manifesto. This will be the moment in which seasoned Palace insiders will be holding their breath. It should be easy—a son taking over from a parent, something the monarchy has managed for 1,000 years. Yet this time, many in the palace believe, the Queen’s death will represent the most constitutionally fraught situation that will happen this century. Why is that? As one source nervously told me, a happy outcome requires “the king getting the tone right.” And not just any king, but Charles.

Fate has conspired to ensure that his reign will follow the most turbulent political era since the Second World War. Ever since the Arab Spring in 2011, dictators have been overthrown, peoples displaced and traditions trashed. The UK has witnessed Brexit and the rebirth of left-wing politics in the space of just 12 months. And in the US, of course, there is Donald Trump. In this context, is the toppling of the monarchy really so far-fetched?

Sure, for the last 80 years, with one notable exception in 1997, the British monarchy has been seen as unassailable—but perhaps that is because of who has been wearing the crown for the last 65 of these years. The Queen is the only monarch most of us have ever known. Over the long decades when Britain lost an Empire but struggled to find a role, she has emerged as the glue that binds the nation together: the very essence of what it means to be British, along with copious cups of tea and stiff upper lips. She is the only public figure around whom (almost) everyone unites. But when she goes, after all those long decades of one Queen keeping calm and carrying on, the monarchy will—inevitably—find itself at a crossroads. It has to choose whether to continue in her rather old-fashioned vein, or become a more low-key, slimmed down European monarchy. In an age where respect for tradition sits at its lowest ebb, and in a context where the new king can only be less popular than what will then be the much-mourned Elizabeth, such dilemmas could easily become poisonous.

With left-wing populism resurgent, and Labour led by a man who does not disguise his personal republican instincts, courtiers privately tell me they dread the drumbeat of radicalism and a future government led by Jeremy Corbyn. In their nightmare scenario, the royals would become a lightning rod for old-fashioned class war. There might not be a march to the guillotine, but a Corbyn administration could easily push for swingeing cuts of a different kind. A large proportion of the royal family’s income—in the shape of the Sovereign Grant—is handed over by the Treasury, from the revenues of the state-owned Crown Estate. Any changes have to be approved by parliament. Earlier this year, even as a freeze on the benefits for poor people was biting, the Queen received an inflation-busting 8 per cent from rising Estate revenues, and—furthermore—a two-thirds increase in her share of its profits was signed off in order to fund a £369m refurbishment of Buckingham Palace. That increase accrues over the next decade. What better way for a socialist government to fund its ambitions than to target the finances of a new and uncertain monarch?

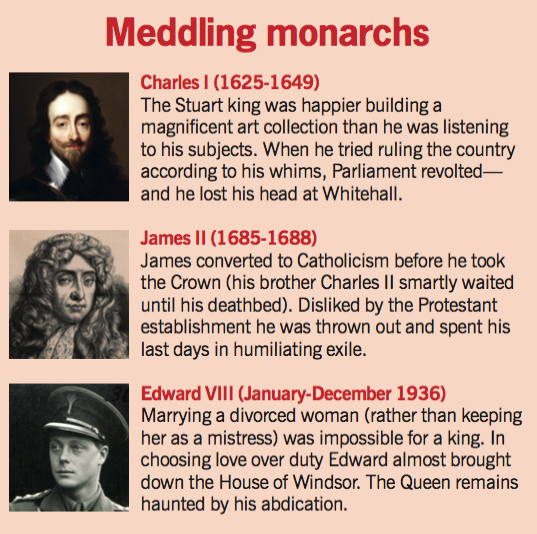

Such a row could push things down the road the family dubbed “The Firm” fear the most. For the first time since the 1930s and the abdication crisis, respectable people might ask whether a “modern” Britain really needs a monarchy at all—and to ponder whether they really are an asset to the state, or just a better-dressed, better-mannered version of the Kardashians.

Charles’s life has been lived in the shadow of his mother, whose well-known mantra is “never complain, never explain.” He will be 69 in November, having become heir to the throne at age three. It is perfectly feasible he will have been in the “waiting room” for 70 years or more by the time he actually inherits. He became Prince of Wales at 10, was invested at 21 and fathered his own heir at 34; all landmarks in the world’s longest spell as an understudy. Few dispute that Elizabeth II has done her strange job well. One of her chief qualities has been knowing when to keep her mouth shut—which is almost all of the time. Her inscrutability, her dedication to duty above everything else (including her own children) and pure longevity mean she will be remembered as one of Britain’s finest monarchs. The first and most obvious contrast with her son is that we know an awful lot about his views, his interests and what he deems important in today’s world.

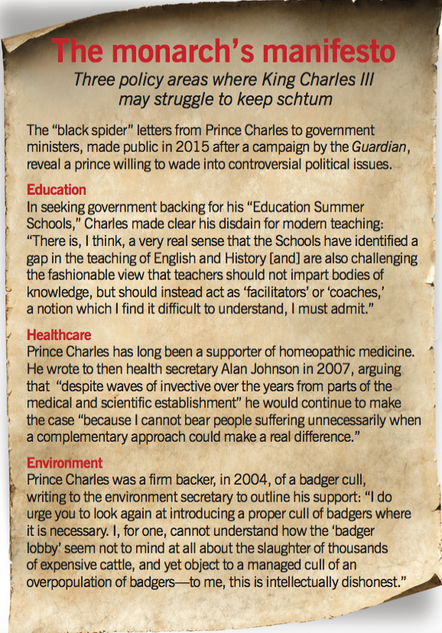

The infamous “black spider” letters (so-called because of his notoriously illegible scrawls) reveal political lobbying of MPs, ministers and even PMs. The topics, from climate change to hospital design, are broad and not easily pigeon-holed. In some moods he is green, in others anti-business, and sometimes he is just plain reactionary. More letters may soon see the light of day. In July, the Information Commissioner’s Office ordered the publication of a series of missives that Charles wrote to then Prime Minister Tony Blair prior to the fox-hunting ban, which came into force in 2005. A keen huntsman, Charles fervently opposed it. The Cabinet Office is resisting publication of what will, surely, be yet another example of the Prince’s incessant attempts to have his say.

With Brexit beckoning, and the Foreign Office using the royals’ “soft diplomacy” to sell Britain abroad, would Charles be able to resist using his prominence to champion more pet causes? He is so passionate about climate change that he helped pen a Ladybird book on it this year, and in 2009, he travelled to Brazil to warn that the world had just 100 months left to save itself from irreversible damage. There are other passions where he has set himself against scientists. The benefits of homeopathy—an interest since childhood—is one. The British Medical Association felt the need to establish an inquiry into it after he made a speech in 1982—it found no evidence to back him up, but he didn’t drop the cause.

Charles, then, has used his current position to lecture experts. Will the same man prove temperamentally capable of maintaining the monarchy’s neutrality by keeping shtum once he becomes king? Or will ministers and diplomats be forced to answer a flurry of communiqués from Buckingham Palace to steer their sights towards the companies and countries that fit with the hobby horses he likes to ride? It doesn’t, surely, take too much of an imaginative leap to visualise the future King Charles III lobbying for congestion and emissions zones to be rolled out in cities and towns across Britain. And one can see why he might regard this as “making a difference”. But the great opportunity, as Charles may see it, could all too easily turn into a severe threat.

If King Charles does indeed turn out to have scope to make more of “a difference” then that is because of the very British “muddling through” manner in which the monarch has historically morphed from a force to be reckoned with into a pure figurehead. Clear written rules about where a king or queen “has to stop” are thin on the ground; everything is governed by copious and sometimes ambiguous precedents. Since the distant days when the early Hanoverians could make or break a prime minister, the constitution has evolved incrementally—and, on occasion, falteringly. Victoria scarcely disguised her preference for Disraeli over Gladstone; George V “commanded” the reluctant Cabinet Secretary to go out and vote for the National Government; it may well have been George VI who persuaded Attlee to make Ernest Bevin foreign secretary, rather than chancellor.

Even the Queen, who is as disinclined to meddle as any monarch can be, has found herself drawn into controversy on occasion, as when she sat on her hands while her governor general dismissed the Australian prime minister Gough Whitlam in 1975. It has taken determination, luck and perhaps judgment to avoid becoming similarly embroiled at home. The potential for trouble was there, for example, when a British general election produced a hung Parliament the previous year. The Queen’s advisers took precautions to avoid her being drawn into a tricky call about how much time to give the defeated Edward Heath to try and cling to power. In a country where Royal Charters are still made by calligraphy on vellum, and where serious powers over pardons and treaties are technically Royal prerogatives, there are ample opportunities for monarchs to find themselves drawn in. The constitutional ground-rules are still summed up in the phrase “the Crown in parliament is law,” which gives any message from the king is—inescapably—a very special status.

But despite Charles’s proven taste for getting involved as a prince, some, like biographer Hugo Vickers, dismiss fears that he “will be too interfering and political” as king. This long-seasoned heir “knows perfectly well that once he’s king he has to be more circumspect. He sees the potential pitfalls and will circumnavigate them.” As a prince, Vickers goes on, he is arguably entitled to intervene. But as king “he absolutely knows what is required”, and will be “sensible”—perhaps doing just “one or two stylish things to make his mark such as commission a new museum or gallery.”

“His ‘black spider’ letters were... ‘written at times in extreme terms containing his view on political matters’”Maybe so. But others who have been closer to Charles are extremely nervous. In a court witness statement in 2006 Charles’s former deputy private secretary Mark Bolland revealed how routinely his boss meddled in politics. “The prince used all the means of communication at his disposal,” Bolland wrote, “including meetings with ministers and others, speeches and correspondence with leaders in all walks of life and politicians… These letters were not merely routine… but written at times in extreme terms… containing his views on political matters and individual politicians… He often referred to himself as a ‘dissident’ working against the prevailing political consensus.” It added: “I remember on many occasions seeing... letters which, for example, denounced the elected leaders of other countries in extreme terms.” It is impossible to imagine Elizabeth committing such thoughts to paper.

Underpinning the fears about Charles’s accession, is the one that never goes away. Will his reign forever be haunted by Diana? Twenty years on from her death, the woman who infamously questioned Charles’s suitability to be king in her 1995 Panorama interview is again uppermost in the nation’s mind. Watched by 22.8m people, that interview led to calls for the crown to skip a generation to Prince William, an idea that is an affront to all monarchical tradition, but one which ICM’s polling for Prospect shows is still popular (p29).

The flipside of what was called, in the great cliché of the time, the “incredible outpouring of national grief” for Diana in 1997 was an intense opprobrium towards her estranged former husband. Real anger was directed towards Charles and the Queen over their perceived coldness and aloof, haughty response. The royal family, shell-shocked by Diana’s death, was caught completely unawares by the wave of emotion—they just didn’t know how to deal with it.

Over the past decade, Charles has, with the help of some skilful aides, managed to rebuild his reputation from the battering it took back then. Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall, is well-liked within the royal family and the public, with possible exception of the oldest generations, are warming to her. And yet Diana is haunting the Prince anew. In Channel 4’s anniversary offering Diana: In her own words, endless footage of the late princess conveyed how Charles had always treated their marriage as a sham, and reported that when she went to see “the top Lady” she was told there was nothing to be done because her son and heir was “hopeless”.

In ITV’s Diana, Our Mother: Her Life and Legacy, her sons William and Harry paid heartfelt tributes, but in doing so—whether consciously or not—they wrote their father out of the script. When William said that his mother gave him “the right tools” for life, some heard a hint that his style of monarchy will be different from his father’s. The boys also organised a rededication of their mother’s grave this year. Instead of using the 20th anniversary of her death on 31st August, they chose her birthday—1st July. This date was right in the middle of Charles and Camilla’s long-planned tour of Canada. The Archbishop of Canterbury was there, as was the then-three year old Prince George. But Charles wasn’t, and it seems likely his sons had planned to make sure he couldn’t be.

Why is Diana so singularly difficult for Charles to handle? After all, she—like him—thought of herself as a rebel, and was very publicly associated with many causes too. And had she ever become Queen, she would surely have shaken things up. But there, perhaps, is the rub. If Diana represented one potential path of modernisation, it is a path Charles would struggle to take. Hugging HIV patients with spontaneous compassion, she was the antithesis of a stuffy, old-fashioned royal. In some ways her death was a liberation: it meant that Charles could marry Camilla and ensured the House of Windsor wasn’t eclipsed by a superstar free-wheeling in their universe. But beside her memory Charles is always painted as an oddball adulterer. So she remains an ever-present threat. If things go well, she won’t be mentioned. If things go awry, her name will be adduced to show how out of touch King Charles is.

For all the forebodings, some of Charles’s courtiers maintain that he will be—as royal biographer Penny Junor puts it—“a super king.” Now that Camilla has banished “the loneliness,” she says, “they’ll make a formidable double act.” He is, she adds, “the best prepared heir to the throne the country has ever had. He’s wise, humorous, well-read and terribly engaged on so many different subjects.”

Charles-sceptics might counter that it is precisely Elizabeth’s lack of “engagement” that has served her so well. After 65 years, the Queen is still a closed book. She grasped young the value of being an enigma: lofty and above indecent inquiry—which primarily means giving no hint of what her views might be. The hope, harboured by some esteemed historians, must be that Charles understands it better than he has shown until now, and will in the end follow his mother’s model.

There is also evidence, for those who are determined to see it, that Charles’s interventions in public life have been a roaring success. In an echo of Victorian philanthropic paternalism, he has used the power of his office to step in where the state has failed. The Prince’s Trust—established by Charles to help young people to get jobs or training—is now 40 years old, and the Prince remains deeply involved. The model village of Poundbury, on the edge of Dorchester, may have been mocked as a “Thomas Hardy theme park,” but it has provided badly-needed jobs and homes. On the outskirts of Newquay, more Duchy of Cornwall land is being used for another ambitious project, Nansledan, which will create affordable accommodation—as well as apprenticeships in traditional building crafts—in an area dominated by second homes. Charles has even had success in business. His Duchy Originals brand sold its first oaten biscuit 25 years ago. In 2009, a deal with Waitrose made it the UK’s largest own-label organic brand (and its biscuits are served with every cup of tea at the royal palaces).

Yet in every one of these many successes, there is an element of turning back the clock. Charles may view himself as a modern man, but his views are more suited to an earlier age. Next year he will be 70—an age when most of us would be putting our feet up. His programme is busier than ever. He never eats lunch, packs his days with engagements and makes every single “grip and grin” handshake an event for the recipient. Twice a year he and Camilla are sent on tours at the behest of the Foreign Office, and with a nonagenarian monarch there will be more heavy lifting.

In a Royal family where change is everywhere, Charles risks looking change-resistant. It is no coincidence that in the year that his grandfather, Prince Philip, has “retired,” William has given up the air ambulance pilot job he loves, to become a full-time working royal. The Duchess of Cambridge and Prince Harry will now be expected to do more too. Meanwhile, there is a changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace: the Queen’s private secretary Christopher Geidt is stepping down, while William and Kate are appointing new personnel. Pointedly, however, there is no change at Clarence House—Charles’s London home.

Senior courtiers whisper that the Queen may make Charles regent when she reaches 95. There is nothing to stop her doing so, and it may allow for a gradual handover, making her death and Charles’s accession less brutal. But after history’s longest wait, a provisional half-reign could simply underline the bigger point. The age at which Charles will take to the throne inevitably means his real task will be to serve as a bridge from the second Elizabethan era and the age of his son. Few doubt that William V will be the first true modern monarch, shaped by Diana’s influence. If Charles can merely hand over without controversy then that, in itself, will mean his reign will have been a success.

It doesn’t sound like a lot to ask. And yet Charles won’t be able to hand over the crown smoothly if he discredits the office. He would do well to remember the Victorian essayist Walter Bagehot’s advice: “We must not bring the Queen,” he wrote, “into the combat of politics or she will cease to be reverenced by all combatants: she will become one combatant among many.” In other words, don’t get involved. To do so would be to forget Bagehot’s wise verdict on the monarchy: “Its mystery is its life. We must not let daylight in upon the magic.” Should Charles III meddle too much, he would find himself doing precisely that—with who knows what consequences for the British crown.

Exclusive Prospect polling: fewer people than ever before want Prince Charles to take the throne