If you want to be seen as a profound thinker, just remember the principle: dark is deep. You must take a dim view of human nature and see its prospects as dismal. There may be more money to be made writing upbeat self-help books promising easy happiness, but you will never be taken seriously in self-consciously intellectual circles unless you are unremittingly gloomy or, as such intellectuals see it, unflinchingly realistic.

Think of the fate of Steven Pinker. Once widely admired as one of the world’s leading psychologists, he is now ridiculed by cognoscenti for his belief that we’ve “never had it so good”—that more human progress remains possible, even likely. Meanwhile, the stature of the likes of Nassim Nicholas Taleb and John Gray, neither of whom I believe has ever been photographed smiling, grows every time they dismiss his data as either wrong or irrelevant.

The Dutch historian Rutger Bregman has emerged as the youthful leader of the rebellion against the doomsters and gloomsters. His first book, Utopia for Realists, argued that with a universal basic income, a 15-hour working week and open borders, we could build a fair and flourishing world. It was a huge bestseller, praised by the likes of the Green MP Caroline Lucas, who said it “adds to a growing list of compelling accounts in favour of radically restructuring our economy.” But the sober mainstream was unmoved: journalist Will Hutton dismissed his three key proposals as “pie in the sky.”

_______________________________________________________________________

Listen to Rutger Bregman discuss Humankind with Prospect's Sameer Rahim

_______________________________________________________________________

The sequel, Humankind, is an attempt to challenge the basic premise on which the more pessimistic orthodoxy rests: that human nature is essentially rotten to the core and that only the constraints of civilised society keep us in check. “Veneer theory,” as the Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal calls it, asserts that underneath the pacific and pro-social cover of civilisation lies humankind’s festering heart of darkness.

Bregman’s tone is chirpy, but he does not attempt to make the impossible case that the human heart is all sweetness and light. His view is simply that we have a “powerful preference for our good side,” one that is hard to override. We may not be wholly good, but we are mostly good.

His takedown of veneer theory is compelling. Meticulously sifting the evidence, he finds that the most pessimistic views of human nature are not backed up by the facts. Indeed, some are solely backed by fiction. William Golding’s novel Lord of the Flies is routinely cited as if it somehow proved that if left to themselves children would inevitably descend into barbarism. Oddly, people rarely talk about the only historical example of a similar case. In 1965, six boys from a boarding school in Tonga were shipwrecked for 15 months on an island, ‘Ata, now classified as uninhabitable. They ended up co-operating, innovating and improvising—and they survived in good physical and psychological shape.

Numerous other myths of essential human depravity are ruthlessly dismantled. If you think war unleashes the inner murderer in ordinary men, consider the growing weight of evidence that it is hard to make soldiers kill, and that most of them don’t even try. One study by the sociologist Randall Collins found that in modern warfare only 13 to 18 per cent of soldiers in combat fired at all. The military has good reason to keep such truths quiet and foster instead the myth of the fearless warrior. The 1914 Christmas truces along the western front so disturbed the generals that they went to great efforts to make sure they weren’t repeated.

Then there is the oft-repeated story of Kitty Genovese, a New Yorker murdered in 1964 on the stairs of her own apartment building. The legend is that 38 witnesses stood by and did nothing, even as the assailant returned twice to inflict more wounds. This became the classic illustration of the bystander effect, the tendency to walk by on the other side, especially when others are doing the same.

The problem is the true story of that murder: most of the neighbours didn’t hear or see anything, and several had in fact called the police, who did nothing. One drunk neighbour notoriously did not intervene, but he had an understandable reason: he was a gay man afraid of drawing the attention of the police at a time when homosexuality was illegal. Yet he did notify a neighbour who bravely went to the stairwell to try to help. Genovese died in her arms.

[su_pullquote align="right"]“Six boys were shipwrecked on an island. They ended up co-operating, innovating and improvising”[/su_pullquote]

This one misreported anecdote and several dodgy lab experiments turned the bystander effect into a widely accepted fact of human behaviour rather than a dubious hypothesis. When a Danish psychologist, Marie Lindegaard, looked at CCTV footage of crimes to see how people actually behaved in real-life conditions, she found that in 90 per cent of cases including brawls, rapes and attempted murders, someone intervened to help.

Bregman is especially convincing in debunking two of the most notorious social psychology experiments of the 20th century. Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment is still widely taken to show that if you give an ordinary person a uniform and authority, they will become a tyrannical monster. Stanley Milgram’s obedience experiments similarly concluded that all it takes is an authority figure in a white coat with a clipboard and people will be ready to inflict potentially lethal electric shocks on their fellow human beings.

Bregman is not the first to discredit either experiment—Prospect ran a piece unraveling both in April last year—but his summary of their failings is damning. In the Stanford Prison Experiment, the subjects playing the role of guards were not left to their own devices but instead strongly coerced into behaving badly. And even then, the original study papers show that two thirds of them in fact “refused to take part in sadistic games.” When the BBC tried to re-run the experiment for a 2002 reality show, this time without any pressure applied, the result was an outbreak of harmony. By day seven, the group had voted in favour of creating a commune. In Milgram’s study, what is striking is how much subjects resisted obeying orders. And there is good evidence that many subjects simply did not believe that they were causing harm, (rightly) assuming that they were involved in some kind of simulation. It would indeed have been incredible if one of the US’s leading universities was actually torturing people.

And yet despite these and other well-documented rebuttals, Bregman writes, “veneer theory is a zombie that just keeps coming back,” often in the guise of whataboutery. What about Auschwitz? What about the Rwandan genocide? What about countless other examples of human depravity?

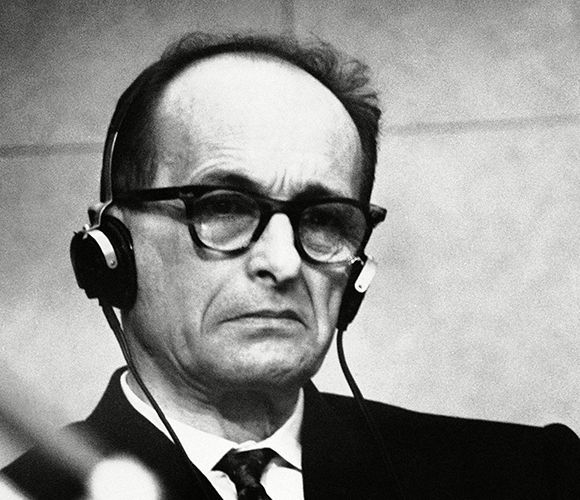

Of course Bregman has to concede that we too often descend into barbarism. But the reasons he gives come with silver linings. For example, while he accepts that some of Milgram’s subjects clearly did act with intentional cruelty, their chief reason for doing so was not sadism but the desire to help. Subjects reported that they hated what they were being asked to do but believed it would benefit science, and thereby eventually help create a better world. The moral of this story is that if you want to make people do evil, don’t appeal to their worst natures—just hijack their better ones. Time and again wrongdoers follow the same justificatory path as Adolf Eichmann, a leading architect of the Holocaust, who “did evil because he believed he was doing good.”

The other generally benign mechanism that can be abused is our capacity for empathy and fellow-feeling. Studies of soldiers suggest that they are not primarily motivated by ideology or nationalism, but by friendship and solidarity with their comrades-in-arms. Just as parents often say they wouldn’t hesitate to kill to protect their babies, soldiers kill primarily to protect each other.

But Bregman does have to concede that these silver linings are attached to some pretty dark clouds. “It seems we’re born with a button for tribalism in our brains,” he says. “Empathy and xenophobia” are “two sides of the same coin.” His concession that the good and the bad are deeply connected jars with the headline message that “most people, deep down, are pretty decent.” Isn’t it rather the case that, deep down, we’re amoral? We have instincts for co-operation and fellow feeling, not because we’re good but because we have evolved to find these things useful. The fact that these instincts can be harnessed for good and evil suggests to me that there is nothing inherently good or bad about them.

Despite Bregman’s occasional willingness to acknowledge our darker side, his is not a balanced appraisal. Instead he offers a piece of advocacy for our better natures that reads like a 400-page TED talk, driven by stories, full of inspirational moments and punctuated by one-sentence paragraphs. It’s brisk and entertaining, but we are swept along too quickly. Although there is no reason to doubt the evidence he presents, it is not selected or framed impartially. Some of his villains, such as Richard Dawkins and Machiavelli, appear in caricature form, while the ideas of thinkers such as Hume and William James are somewhat distorted.

The strongest indication of imbalance is in the contrast between his strongly evidenced debunking of the pessimists, and his much more anecdotal case for the optimists. Bregman is on reasonably solid ground when he advocates for the humane Norwegian prison system and for citizens’ assemblies, both of which have been widely studied. But much less so when—on the strength of tales about an inspirational head of a Dutch healthcare company—he gushes about revolutionary management. Jos de Blok’s ideas are, supposedly, “on par with cracking DNA.”

So what are they? His company is based on the principle that staff should be driven by intrinsic motivations and do a good job for a positive social purpose, not extrinsic financial ones. It sounds wonderful (if not entirely novel), but it is just an anecdote. Is the secret of de Blok’s success really the managerial attitude that Bregman notes, or could other factors be more important? His brief mention that the company’s “overheads are negligible” due to its lack of an expensive head office suggests there is more to this story than progressive leadership. Similarly, his visit to an equally inspirational alternative Dutch school, Agora in Roermond, makes it sound idyllic, with students drawing up individual plans with “coaches” rather than teachers. But one brief, breezy eulogising chapter does not add up to an argument that the model is replicable, much as I’d like to believe that it is.

Despite its excesses and its breathless enthusiasm, the book works as a much-needed corrective to excessive pessimism about human wickedness. But why is such a corrective needed? Why are we so well-disposed to the view that we are not generally well-disposed?

[su_pullquote align="right"]“Bregman’s book is an attempt to challenge the basic premise on which the more pessimistic orthodoxy rests: that human nature is essentially rotten to the core”[/su_pullquote]

Bregman argues that “to believe in our own sinful nature is comforting… it provides a kind of absolution.” If that’s just how people are, there’s no point feeling guilty over our own failings or getting too bothered by those of others. He also highlights two important psychological mechanisms at work. One is negativity bias. We are more alert to the bad than to the good, presumably for evolutionary reasons. For survival purposes, we need to be much more attuned to potential threats than to what is harmless. The cost of failing to notice a lion is much higher than the benefits of noticing a kitten. Thanks to the omnipresence of news, we’re also affected by availability bias. We pay more attention to what we see most and the news is filled with tragedies. This theory seems intuitively plausible, but given that intellectual pessimism long predates 24-hour news, it can only be an intensifier rather than a cause of our fundamental distortion.

Bregman argues that we need to counter our gloomier tendencies because “our grim view of humanity” is a “nocebo.” Just as placebos have positive effects simply because people believe they do, nocebos are negative expectations of treatment or prognosis that become self-fulfilling prophecies. One nice piece of evidence for this are the studies that show the longer students study economics, which teaches them that human behaviour is motivated by self-interest, the more selfish they become. A society in which people assume the worst about human beings will be one that has coercive penal systems, authoritarian schools and low levels of trust, all things that will make matters worse.

Bregman clearly thinks that the flip side of this is that belief in human goodness can act as a placebo. If he’s right about that, it hardly matters if many of his claims are factually true: believing them will make them so. He doesn’t undersell the extent to which positive beliefs can lead to positive actions. “Kindness is catching,” he says. “And it’s so contagious that it even infects people who merely see it from afar.”

But his evidence is again anecdotal. If kindness truly did have an R value of above one, the world would be full of loveliness and his book wouldn’t be needed. In his cries for the potential snowballing effects of good deeds we can hear the echoes of so many empty hopes of the past. People sincerely believed that the 1967 Summer of Love was going to usher in a new Age of Aquarius. Soon after Live Aid in 1985, an article by Stuart Hall and Martin Jacques in Marxism Today claimed that “A new politics sweeps the land” and that “the ideology of selfishness… has been dealt a further, severe blow.” Right now people are quick to predict that the new sense of community fostered by the Covid-19 lockdown will change society for the better, forever.

The world is never as grim as some fear or as sunny as others hope. The debate about whether human nature is essentially good or bad is pointless. The answer is that it is neither. We have the capacities for love, kindness and sympathy and also for hatred, malice and selfishness. To ask which set of characteristics comprises our essence is like asking whether a Manhattan is actually whiskey or vermouth.