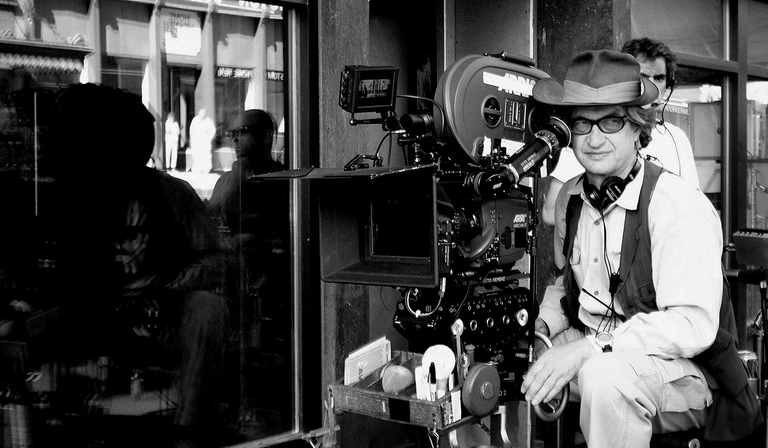

Wim Wenders turned 80 this summer. He started making films six decades ago, in 1967. Unbelievable! In the 1980s and early 1990s, freshers would tack posters of Paris, Texas on their dorm room walls—next to those of Eraserhead and Betty Blue. Wenders had an edge: like Lindsay Anderson, like François Truffaut, he was a critic before he was a director. He had been an angry young man, part of the New German Cinema movement that denounced its peers for being too cosy and commercial. Passionate about American mavericks such as Nicholas Ray and Sam Fuller, style (he made a film about designer Yohji Yamamoto) and leftfield pop music, he seemed utterly à la mode.

Wenders could have taken many roads. He studied medicine, then switched to philosophy. He was tempted to join the priesthood. The economic miracle of 1950s Germany meant nothing to him: it hinged on collective amnesia. Cinema itself was troubling: the nation, he believed, was “highly susceptible to images and already almost totally engulfed in foreign images”.

His films, among them Summer in the City (1970), Alice in the Cities (1974) and Wrong Move (1975), were photographed in atmospheric black and white by Robby Müller. They featured brooding men—newly released prisoners, struggling writers—as they drifted through and across Germany. Pregnant pauses, scant dialogue, always dislocation: these were distinctly European takes on the American road movie genre—shorn of yee-haw rebellion or transcendence, closer in spirit to philosopher Theodor Adorno’s claim that, “Ethics today means not being at home in one’s house.”

Paris, Texas (1984) may be Wenders’s greatest achievement. Harry Dean Stanton plays a dazed, initially mute figure, separated from his son and family for reasons which are revealed slowly and to devastating effect. There’s a powerful soundtrack by Ry Cooder and an indelible performance from Nastassja Kinski. Müller captures the lonesome, keening landscapes of inland America with prickled fascination.

Wenders returned to Germany in 1984. “The landscapes of John Ford are now Marlboro Country, the American Dream has become a marketing campaign,” he later recalled. “I came home in part because I could no longer stand Disneyland: the breath of ‘true images’ no longer exists, only the bad odour of lying images.” It was a wise decision: his next film, Wings of Desire (1987)—co-scripted by a long-time collaborator, the Austrian writer Peter Handke—was a philosophical romance about two angels watching over and listening to pre-unified Berlin.

At that point, Wenders’ critical and commercial standing began to slide. Was this self-described “German Romantic” too earnest, too marinated in a postwar Weltanschauung for a postmodern “indie” film culture? Spike Lee, furious that Do the Right Thing had lost out to Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival, declared that Wenders (who chaired the Palme d’Or jury) “better watch out ’cause I’m waiting for his ass”. Even Buena Vista Social Club, a 1999 valentine to semi-forgotten Cuban musicians, was attacked in some quarters for being nostalgic.

Was this self-described ‘German Romantic’ too earnest for a postmodern ‘indie’ film culture?

In recent years, aside from Perfect Days (2023)—his swoony drama about a toilet cleaner in Tokyo who finds peace in his daily rounds, old cassettes and the interplay of trees and light—Wenders has mostly focused on documentaries. Like many filmmakers, he finds them less shackled to genre or hokey formulae. Their subjects, like him, are older masters. They’re underwritten, he has confessed, by a clearer political vision than in the past: “Any film that supports the idea that things can be changed is a great film in my eyes.”

Pina (2011), a portrait of German choreographer Pina Bausch, skimps on biography and dance history; instead, through silent montage and electrifying use of 3D, he shows her visions being channelled by the international crew of men and women who worked with her at Tanztheater Wuppertal. One of them shares a vivid memory: “She moved as if she had a hole in her tummy, as if she’d risen from the dead.” The Salt of the Earth (2014) follows Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, burnt out by decades of chronicling famines and genocides, as he finds solace in greening an arid valley where his father owned a ranch.

Anselm (2023)—about artist Anselm Kiefer—is an oblique autobiography. Here is another German, also born in 1945, the creator of a vast corpus “against forgetting”. There are quotes from Celan and Heidegger. High-concept shots depicting Kiefer on a tightrope over the Ruhr. Metaphysics and droll humour. Miraculously, Wenders is making some of his best films of his career. Happy birthday, Wim: keep (almost) calm and carry on.