Barack Obama is effortlessly cool. His post-presidency photographs showed him jet skiing on Richard Branson’s private island. Every year, he gives us a Spotify playlist featuring hip-hop, soul and jazz. His mic drop moment will forever be in our meme library.

So it was of little surprised that the coolest president ever chose Kehinde Wiley to immortalise him in the Smithsonian public presidential collection. Wiley—who is also a popular and cool contemporary painter—is known for creating grandiose masters of African American subjects, re-imagined as noble figures.

The portrait of Barack Obama was slightly different from his usual style, apparently as per his request. It may have been this that compelled Wiley to portray the president without a tie, capturing his self-assured, free personality without any props to bolster his authority.

Obama floats against a background of flowers and foliage, with his wedding band one of the only items visibly on show—thus signifying to future generations that not only was Obama the most powerful man in the world, he should be remembered as a loving husband, rather than embroiled in insecure hypermasculinity like his successor.

With this in mind, it’s something of a shame that a different artist was chosen to paint former first lady Michelle Obama. Barack Obama has always spoken about his and Michelle's loving relationship.

In a joint interview with Oprah in 2011, he said “you were asking earlier what keeps me sane, what keeps me balanced, what allows me to deal with the pressure. It is this young lady right here ... not only has she been a great first lady, she is just my rock. I count on her in so many ways every single day.”

The couple were a real life, black visual representation of power, marriage and family success, the Obamas became a source of inspiration for many young black people —who would instantly post #goals underneath photographs of them together.

Commissioning one artist, instead of two may have led to a deeper, intrinsic story being told about America's first black presidential couple. I would have been in favour of giving Lina Viktor this challenge.

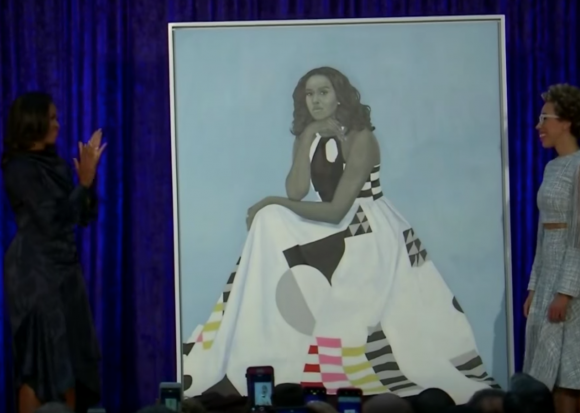

Amy Sherald’s official portrait of the former first lady Michelle Obama, also unveiled on Monday at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, was in direct contrast to the literally eye oscillating Wiley portrait.

Although still eye-catching, this portrait requires viewers to stare sternly to capture the “mountain” described by Doreen St Felix in the New Yorker,“Obama sits against sky-blue oblivion, the triangular shape of the dress turning her into a mountain.”

Hidden in plain sight is an ode to African American women artists, the Gee’ Bend Quilt makers. Amy Sherald features some of their style of patterning and geometry on Mrs Obama dress that is present within the quilts.

It takes a moment for viewers to visually re-code and see the mountain configuration. Although Michelle Obama may not have earned quite as many cool stripes as her husband, her legacy will be used as an example to black girls that it is not only possible to reach the mountain peak, but become the mountain that spectators will look upon with awe.

Yet the painting was met with criticism in some quarters. Co-chief art critic at the New York Times, Holland Cotter, describes a feeling of emptiness when looking at the painting: “To be honest, I was anticipating—hoping for—a bolder, more incisive image of the strong-voiced person I imagine this former first lady to be.”

Looking attentively at the portrait, there are moments I too asked myself, “Who is Michelle Obama again, and what did she stand for?”

This may partly be down to Sherald’s style. Sherald, who privately trained with Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum, has discussed the use of greyscale as an aesthetic preference.

Mixing black and naples yellow, she realised, looked visually fantastic—and in her artist statement explains that she paints skin colour with a grey palette as a way to “exclude the idea of color as race.” The technique creates dazzling imagery.

Yet social media users—who at times play the role of micro art critics—were quick to pick up on the lack of brown present in Michelle Obama’s skin. (Perhaps this is why Sherald opted to switch off the comments underneath her Instagram photo of the portrait.) It’s true that the erasure of her melanin renders her forgettable,particularly compared to her husband’s portrait.

In the past, the former First Lady had spoken so candidly about race and its impact on her family history, so it’s really hard to understand why she chose an artist who negates this detail from her paintings. Maybe the point was not to see Mrs Obama’s race, but instead feel the black First Lady's historical ascension by just celebrating the portrait's form.

For some, the criticism was a step too far. Elizabeth Wellington, a columnist at the Philly Inquirer, wrote that “these portraits—the first ever to be commissioned by African American artists for the National Portrait Gallery—aren’t about me and how I want to remember the Obamas. Nor are they about you, or how you want to see them.”

But, whether you agreed with criticism of Sherald’s painting or not, it was refreshing to see so many black people engage publically in art discourses.

The black community are an under-represented in both the USA and UK museum audiences. Recent research from Arts Council England, found that ethnic minority audiences were “consistently underrepresented” in publicly funded art organisations. This maybe because black people are notably absent from public collections therefore most exhibitions fail to speak to, or reflect a likeness of, our version of history.

Public programming also fails to capture our interests and tastes. Curator Sumaya Kassim argues that “for many people of colour, collections symbolise historic and ongoing trauma and theft. Behind every beautiful object and historically important building or monument is trauma.”

For someone who works to deliver more diversity in the art world, it was great to see so many black people speaking about the official portraits. While some may be frustrated by criticisms, we must not fall into the traps that reinforce elitism in the art world by deciding who and shouldn’t be allowed to critique art. None of our voices should be silenced, and engagement should be encouraged.