An Ipsos MORI poll in March placed health care second only to Brexit as the key issue for voters in the general election. What’s more, the NHS tops the list of what makes us most proud to be British: potentially important in an election where many issues are likely to be refracted through the prism of national identity. But when Ipsos MORI surveyed 23 countries in a recent study, it found that the British are the most pessimistic about the future of health care. Only 8 per cent of Britons think the NHS is going to improve in quality.

The most recent data from NatCen Social Research’s British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey, collected in summer 2016, shows that satisfaction with the NHS is relatively stable. But since 2014, the proportion thinking that the NHS has a major or severe funding problem has increased from 72 to 82 per cent. The public’s awareness of the pressures on the NHS is increasing, even if this has not yet affected their satisfaction with services.

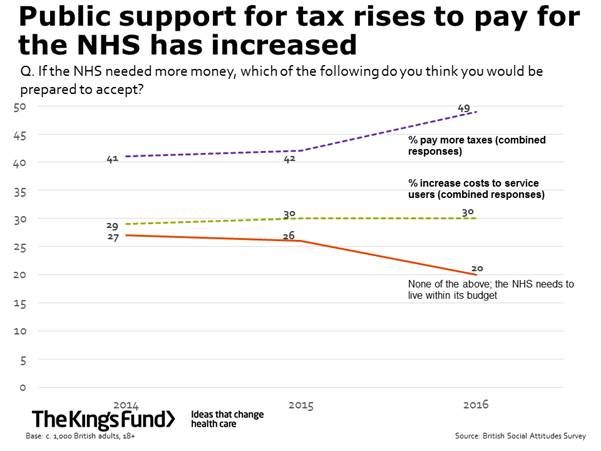

Given these pressures, tough choices will need to be made about how to pay for the NHS. The public need to be involved in that discussion and they are increasingly ready to have it. The latest BSA data shows the proportion of Britons who would accept tax rises to increase NHS funding has grown by eight percentage points since 2015, to nearly a majority (49 per cent). This increase is largely mirrored by a fall in the proportion of people who say the NHS needs to live within its budget.

There are caveats to this. Over half of the public would still prefer solutions that do not involve raising taxes. And of course, the scenarios presented in surveys are hypothetical—it isn’t certain that a concrete proposal would find as much favour. Ipsos MORI research conducted in 2017 shows that support for raising taxes to pay for the NHS decreases as the tax rise is seen to hit more people. The same poll showed that raising national insurance to pay for the NHS attracts a greater majority than raising income tax.

But while the public might be ready to talk taxes, politicians may not be. So, what can be delivered within the current budget and what do the public think should be prioritised? Opinion on this is divided. If the NHS budget is not sufficient to deliver current levels of service, the BSA shows that 43 per cent would stop providing treatments that are poor value for money. However, an increasing proportion of people—28 per cent, up from 23 per cent in 2015—think that the NHS should restrict access to non-emergency treatment.

Rationing services is controversial, as recent coverage of blanket bans for some elective treatments demonstrates. But the data from the BSA shows that the public are capable of weighing up difficult decisions, and controversy should not stand in the way of open and honest debate. The general election offers an opportunity to reset the national conversation about how we pay for the NHS and engage people in the big questions about its future. The public has an opinion on the future of the NHS, but are politicians willing to listen?