I’m one of the luckier ones. Among my close friends growing up, one was groomed and raped aged 14 by her 28-year-old “boyfriend.” Another was attacked and raped by someone she’d been dating (he was angry when she dumped him). Another was left with catastrophic injuries from childbirth, which made further pregnancies perilous. We were privileged, educated, fairly savvy teenagers, then young women, then mothers. Whether through shocking instances of violence, or the blurred edges of consent, or mundane contraceptive accidents, we all have our stories.

I thought about those stories when Texas’s draconian new abortion ban came into effect on 1st September. The law effectively forbids abortion after six weeks, even in cases of rape or incest; many other states plan to follow suit. I imagined the potentially life-changing consequences for any of us, had we been subject to such a law—if we’d been robbed of the right, say, as teenagers to protect our bodies from unwanted pregnancies or, later, to act in the best interests of our existing children. (More than half of American women seeking abortions are already mothers.) Worse still, the law hits those far less fortunate than us harder: women from poorer and ethnic minority communities, with fewer resources to travel, access information or to pay for out-of-state care.

For religious conservatives, this moment is both a major victory in a decades-long campaign, and a harbinger of more to come. The Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision not to act against the Texas law is the strongest signal yet that the Trump-stacked bench is on the cusp of overturning Roe v Wade, the landmark 1973 ruling that created a federal right to abortion. Its demise will most likely be formalised in December, when the court hears a case testing a 15-week abortion limit in Mississippi. More than 20 states have “trigger laws” ready; should Roe fall, they will immediately outlaw abortion across swathes of the country. It will be a potent rallying call for authoritarians peddling so-called “family values” across the world, from Hungary to Brazil.

And yet, will we look back and see this as a moment of fatal overreach for America’s anti-choice crusaders? Even as family planning services have been gutted for years across the US, activists and communities have been building alternative networks to serve women who need help: volunteers who will drive you across states, funds to cover your costs, and—most irrepressibly—pills you can order online. Roe may fall victim to a captured Supreme Court, with devastating consequences for many women. But the ground war will continue: county by county, state by state. And it’s not impossible that this latest power grab, imposed by an entrenched and increasingly anti-democratic minority, could ultimately lead to a decisive fightback for women—and liberal democracy.

The lives of others

“It just seems, I know this sounds ridiculous, almost un-American,” Joe Biden said right after the Texas law, known as SB-8, was passed. “The most pernicious thing about [it] is it sort of creates a vigilante system…” He was referring to the unique innovations of SB-8, which appear to have finally delivered the legal formula the anti-abortion lobby have sought through hundreds of court and legislative efforts over decades. It outsources enforcement to private citizens: paying “bounties” of at least $10,000 to anyone who successfully brings a lawsuit against someone for providing or aiding an abortion. It’s been described as the “random motherfucker clause”: enabling a resident of, say, Arizona, Wisconsin or Maine to hunt out an abortion bounty in Texas, so long as they can find a suspect.

In empowering citizens rather than state officials to bring cases, the law blocks off the obvious route of challenge. For the question is, who can be sued for imposing it? At least until private citizens actually bring cases, the answer has been: no one. Even as abortion providers and Biden’s Department of Justice issued a volley of lawsuits of uncertain effectiveness against the new Texas law, legislators in other states—from Florida to South Dakota—signalled they were preparing to introduce similar laws.

In another twist, SB-8 does not target pregnant women directly. People who have terminations cannot be sued: only those who provide them, or who “aid and abet.” It’s a provision so vaguely worded that it could implicate an Uber driver who takes someone to a clinic, or a neighbour who gives a friend a lift over state lines, or a receptionist who happens to work at Planned Parenthood. It is, says Sarah Shaw, head of advocacy at MSI Reproductive Choices, “terrifying”: “You’ve got a so-called liberal democracy, with institutions that are supposed to protect citizens, now suddenly saying to them: ‘you will be hunted down.’”

Though oblique in some ways, SB-8 nakedly stacks the scales of justice in favour of the bounty hunters. For example, even if you successfully defend yourself against a court claim under SB-8, you will still have to pay the other side’s (potentially large) legal costs. An unlimited number of lawsuits can be brought for the same alleged abortion. You can be sued anywhere in the state: you may live in Houston, but if that “random motherfucker” decides the case must be heard, say, 500 miles away in Guthrie, King County, then to Guthrie you must go.

The effect has been swift—and dramatic. Whole Woman’s Health operates four clinics in Texas, in McAllen, McKinney, Austin and Fort Worth. Before 1st September, over 90 per cent of the abortions they provided were past the six-week mark (a time-limit dated from your last period, meaning that many women, particularly those with irregular cycles, won’t know they are pregnant). Just days after the law came into effect, Marva Sadler, senior director of clinical services, told me they’d had to turn away more than 100 women; none had alternative plans. It’s inevitable that some women will resort to risky, brutal methods. Meanwhile Nicole Martin of Indigenous Women Rising, over the border in New Mexico, reported that as lives were put “into the hands of strangers,” there was a flood of calls for help. “We are completely burnt out, working crazy hours,” she said.

It is ironic that libertarian Texas, with its famously permissive gun laws, has pledged unlimited taxpayer dollars to turn everyone into a potential arm of government. It not only infringes the freedoms of medical workers to supply services, or friends to support one another. It also actively enlists anyone willing to turn their hand to interfere. And what about social media companies exercising their “American” constitutional right to free speech, if that speech happens to contain information about how to get an abortion—will they also become targets? Or will they comply?

“It’s like something from the Handmaid’s Tale—I thought at first these US pro-choice activists were exaggerating,” said Neil Datta, speaking to me from the European Parliamentary Forum for Sexual and Reproductive Rights, based in Brussels. “It wouldn’t be out of place in Soviet Russia or Nazi Germany: respectively pushing people to ‘out’ capitalists, communists or other enemies. Surely this was part of our past. I thought we had a collective memory that these things were bad.”

Global crusade

Is Biden entirely right to call the law “un-American?” His description not only ignores America’s rich tradition of vigilantes and militias, dating to the founding days of the republic, referred to in the constitution and on full display as recently as 6th January in Washington. It also glosses over some of the darkest chapters in American history—including McCarthyism and the Fugitive Slave Act, a sweeping federal law that deputised citizens to surveil, chase down and render people fleeing slavery. Hefty financial rewards were offered both for the capture of slaves, as well as for the successful prosecution of those who dared to help them.

But nor is there anything uniquely American about this type of outsourced authoritarianism. Recall that in Britain, a “hostile environment” that gave rise to the Windrush scandal continues to turn landlords, employers and others into agents of the Home Office. As MSI Reproductive Choices’s Sarah Shaw puts it, the new Texas law sends a clear message to “authoritarian governments everywhere,” namely “have you got groups—young people, racial or ethnic minorities—who are giving you trouble? This is how you clamp down on them.”

Indeed, in some senses, the US Christian right is better positioned to capitalise on this moment abroad than at home. It has often run into less powerful opposition when it has aggressively pushed its agenda across Africa, Latin America and, increasingly, Europe. Our continent is more promising territory than you might think: nothing in its human rights framework has traditionally given anything akin to the right the Supreme Court ingeniously summoned from the constitution in the form of Roe. Abortion was almost completely banned in Ireland until a 2018 referendum, as it continues to be in Malta and increasingly is in Poland.

Last year openDemocracy, the global news website I used to edit, reported that leading US Christian groups have spent more than $280m overseas since 2007—likely a fraction of the true figure, since many are registered as churches and so are exempt from declaring expenditure in the same way. These groups have resourced everything including court cases and protests in Britain, where Shaw reports an uptick in well-financed anti-abortion demonstrations outside clinics. In places like Uganda, heavily targeted by US religious groups, there are stark parallels between the new Texas law and the state-mandated persecution of LGBTQ+ people. (Ugandan doctors are required by law to report anyone they suspect of being gay; Ghana’s parliament is currently debating a similar bill.) In Uganda, too, there are reports of “Unwanted Pregnancy Surveillance Teams,” which train volunteers to identify and target women who may be considering an abortion. Lydia Namubiru, a Kampala-based journalist, worries that countries like hers can “act as testing grounds: places where US culture warriors can pilot and hone tactics later deployed back at home.”

Along with American cash comes legal support. Last year, the American Center for Law and Justice—run by Trump’s personal lawyer Jay Sekulow—submitted amicus briefs to Poland’s Constitutional Court, supporting its landmark decision to heavily restrict abortions. Other US groups have been making inroads with European far-right forces such as the Lega in Italy, Vox in Spain and the increasingly-despotic Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán. Former vice president Mike Pence was one of the luminaries who recently joined Orbán at the fourth annual Budapest Demographic Summit. On the agenda: how to deal with “attacks on family values.” Hungary has been criticised for obstructing abortion access by, in the words of a UN report, imposing “unnecessary waiting periods” and “hostile counselling.”

Both in the US and globally, religious conservatives have shifted the goalposts, even the language. Just as an earlier generation of American right-wingers achieved huge giveaways for the rich by rebranding the bureaucratic-sounding “estate duty” as the emotive “death tax,” so today’s conservatives have succeeded in getting Texas’s SB-8 and copycat statutes elsewhere debated as heartbeat laws, irrespective of the fact that fetuses do not have “hearts” as such at six weeks.

Meanwhile, SB-8 succeeds in making the upcoming Mississippi abortion case, due to be heard by the Supreme Court in December, seem tame by comparison. In this instance, the court is being asked to consider the legality of a state 15-week abortion term limit. After Texas, that sounds newly reasonable; softening up the presentation of the Mississippi case that is designed to confront, head-on, the half-century of legal precedent established by Roe. The nine justices will be asked to do what the Court has repeatedly declined to do; to rule that their predecessors got it wrong in 1973, and that there is no right to choice implicit in the constitution. Nothing will have changed except for the composition of the court, including a trio of conservative appointments, two deeply controversial, by Donald Trump. But that could be enough.

Deeper tides

Yet for all the money, advocacy and litigation deployed by American evangelists at home and abroad, some winds are blowing the other way. Days after Texas passed SB-8, the Supreme Court in heavily Catholic Mexico, just south of the border, issued a sweeping ruling that no state in that country could criminalise abortions. (They are currently only legal in four of 32 states, so this is a gamechanger.) Argentina became the first big Latin American country to fully legalise abortion last year; Colombia could follow suit. Diana Cariboni, an openDemocracy journalist based in Uruguay, reflects that the Texas law and the anticipated fall of Roe could embolden a reaction from politicians and courts elsewhere on the continent, to distance themselves from the “extremist” superpower to their north. Of course, Latin America starts out from the opposite place: abortion is still heavily restricted in most countries. But Chile’s ongoing constitutional process, which looks likely to enshrine a broad range of reproductive rights, provides further grounds for hope.

Indeed, it is telling that, in many places, legislators have pulled off regressive laws over women’s bodies only by defying majority democratic opinion—and often the democratic rulebook, too. Poland and the US itself are instructive examples here. In both countries, most people support legalised abortion. Poland’s near-total abortion ban, which sparked massive protests, was only passed last year after the ruling Law and Justice Party had stacked the court with compliant justices. Similarly, to entrench the hardline conservative majority that has already allowed the Texas law to proceed and will, very likely, overturn Roe, the Republicans had to play dirty for years: arbitrarily but successfully blocking Obama’s amply-qualified Supreme Court nominee to keep an extra seat open for Trump to fill.

Ultimately, these aren’t only battles over women’s bodies. They are also tests for democracy. In the US, Republican politicians are increasingly abandoning any pretence of majoritarianism. SB-8 came right on the heels of sweeping measures to restrict access to the ballot in Texas—mirrored in Georgia, Florida, Arizona and a dozen other states since Trump’s loss in November 2020. For them, the game isn’t about winning a plurality through attracting centrist votes: it’s about capturing the institutions of state, and doubling down on their base. History suggests this approach ends badly—and not only for women.

However, all may not be lost. Those intensive efforts to restrict voting are animated by a deep drift of both demographics and social attitudes against Republicans. Moreover, the fall of Roe will not usher in a blanket ban on abortions: “blue” states will continue to provide and fund a range of family planning services, and will also offer safe havens for women seeking abortions out of state.

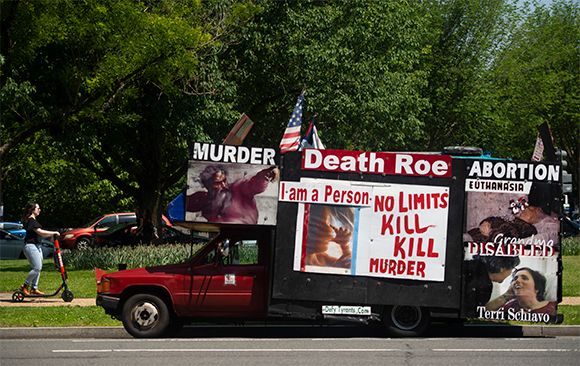

Meanwhile the tide of technology and medicine is only going one way. During the final days before SB-8 came into effect in Texas, a big truck emblazoned with illuminated billboards was making its way around the state. “Missed period? There’s a pill for that…” flashed a big blue message on both sides of the vehicle, as it travelled from town squares to college campuses across Lubbock, Amarillo, Midland and Odessa.

“We went on an abortion road trip to let people know that you don’t need to go on a road trip anymore to get an abortion,” Elisa Wells, co-director of the pro-choice group Plan C, told the magazine Ms. “You can get an abortion by mail basically anywhere in the United States, including in Texas.”

As in many other countries, Covid-19 has sparked a dramatic increase in abortion via telemedicine: ordering pills (mifepristone and misoprostol, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for up to 10 weeks’ pregnancy). The laws were also liberalised in the UK in March 2020, to permit at-home terminations up to 11 weeks. So-called “medical” rather than “surgical” abortions have been legal in much of Europe for decades, with up to 90 per cent of women opting for them in countries like Finland. In the US, while telemedicine abortion is now legal in many blue states, restrictions remain, and many red states (including Texas) have outlawed them altogether. But in reality, blanket bans on obtaining abortion pills online are extremely hard to enforce at scale.

Medical abortions are not appropriate in certain circumstances, including in more advanced pregnancies or where there is an elevated risk of complications. But for millions of women, they do the job. Speaking on the phone from California after SB-8 came into effect, the other Plan C co-director, Francine Coeytaux, was bullish. “Could we do that roadtrip in Texas again now? Of course we could,” she said. “Sure, the risk of us getting sued is higher. But the reason we did it was to stand up to the bullying. People in Texas need to know they still have options.”

Plan C’s website provides location-specific tips for telemedicine options across the US, and also information about international services like AidAccess and online pharmacies that will send pills from abroad, circumventing state or national bans. They also provide this service to women in countries where abortion remains overwhelmingly illegal, like El Salvador and Nigeria. Much as we’ve seen over decades with the illicit drugs trade, it just isn’t possible to contain this: even with the threat of draconian punishments.

“They’ve overreached,” said Coeytaux of the Texan legislators, and that has “forced us to get even more creative.” Plan C already points people towards such options as setting up a mailbox in a state that allows remote abortions, and provides legal advice on the risks.

Self-described pro-lifers fear that the Texas law will backfire, too. Sam Sawyer, writing in the America Jesuit Review in September, worries distaste at bounty-hunting could inspire “fear and distrust,” asking: “Will the Texas law make it easier or harder to convince our fellow citizens to adopt laws that will protect the unborn and support women facing unwanted pregnancies?”

Even US corporates are starting to row in behind Texan women: Uber and Lyft have both said they will cover the legal costs of any drivers targeted by SB-8. The tech firm Salesforce, along with many others, is offering to cover the costs of employee’s permanent relocation out of the state.

The surge in funding now pouring into organisations such as Planned Parenthood, Whole Women’s Health and Plan C will finance further court challenges and pro-choice buses. It will also support targeted Google ads providing women with better information about how they can get help, outside and around the law. Lawsuits and counter-lawsuits are likely to ensue; but there’s a palpable new energy and defiance now.

Underscoring all of this is the fact that religious conservative attitudes towards sex and women’s bodies are on a likely irreversible slide. While church membership in the US held up for longer than in Europe, since the turn of the century it has been in sharp retreat; only a minority of declared Catholics attend church; evangelicals—who form the Christian conservative base, especially in the south—are dwindling. Even among voters who generally lean to the right, many of the younger ones are finding it increasingly hard to stomach the Republican agenda on—as one swing voter in Georgia put it to me—“bodies and science.” “I might agree with some of their political views but… what a woman does with her body is not anyone’s business except hers,” she said. “It is really confusing to me that anyone would think otherwise.” She voted Democratic “almost out of spite” last year—as did her state, which turned blue for the first time since 1992.

They may have gamed the system for now, but deep tides—demographic, religious, technological and generational—are running against the Republican zealots. Despite the cruelty they have unleashed in Texas, and even the long-anticipated defeat of Roe, they could yet fail in their wars against women’s bodies and science. “We are not going to be silenced,” said Coeytaux from Plan C. “Our government has refused to put the pills we need over the counter—so we’re going to put them into the medicine cabinet directly. And just try and stop us.”