Could France fall to the extreme right for the first time since Vichy? Until recently such a thing seemed impossible. Now it feels as though it could happen. In January, a YouGov poll found 38 per cent of French people thought a victory for Marine Le Pen—the leader of France’s far-right party, the Front National (FN)—was “probable” despite no poll of voters predicting she will become president. Why this gap between what so many people, including myself, know to be likely and what we believe?

Despite the evidence, I fear Le Pen could win. Not just because Brexit and Trump show anything is possible, but because for the first time in the Fifth Republic, France’s crash barrier against the lure of extremism—the electoral system—no longer feels reliable.

Introduced under Charles de Gaulle in 1962, the two-round system was designed to keep extremists out of power. Candidates must either receive an absolute majority or go to a run-off between the two candidates with the most votes. Typically, French electors use the first round to vote with the heart—expressing things like hope, desire, rage or downright blood-mindedness—and the second round to vote with the head. Something about the way in which Marine Le Pen has infused the national conversation with despair makes me doubt the barrier will work this time.

In one sense, France is just one more democracy bound up in an angry, post-crisis, anti-globalist mood. Le Pen’s arguments echo “take back control” and “America first.” But in another sense, France is different. The FN is not Ukip. It is a powerful movement that has been putting down organisational roots for three decades; this in a culture built on idealism, where despair could lead, has led in the past, to democratic suicide.

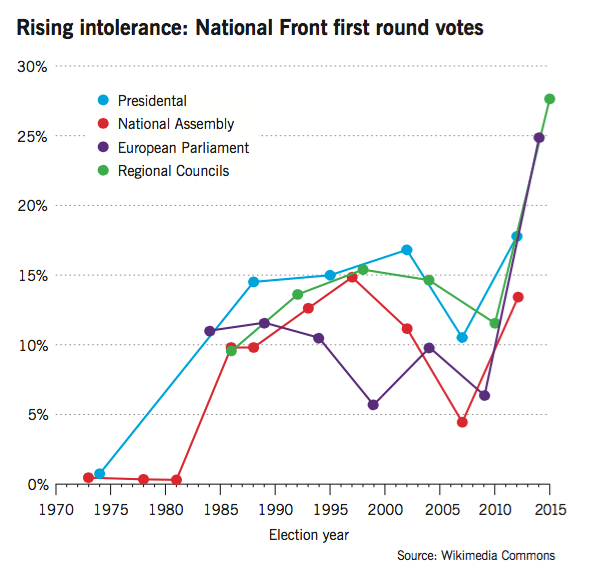

Ever since I moved to France in the 1980s, I have watched the FN base swell, and its electoral gap with the mainstream parties narrow. The potential for xenophobia was always there. Beneath the surface of the republic’s founding equality myth, France’s version of it morphed from the anti-Semitism that dominated in the 20th century, to the Islamophobia—rooted in France’s colonisation of the Maghreb—that dominates today. Its actualisation as a serious political force, however, has relied on profound social and political changes:: the withering of the old Communist Party to which swathes of the working class had owed allegiance and the entrenchment and broad acceptance of high unemployment. The FN now runs 14 town halls, in the south of the country where it is strongest, and in the post-industrial north and east where, under Marine Le Pen, it has managed to oust the extreme left from blue-collar communities.

All French politicians are aware of the dangerous force that is xenophobia. Some harness it. In 1986, the then-embattled Socialist President François Mitterrand, cynically seeking to split the right on the matter of how to deal with extremists, introduced proportional representation for the legislative elections. Until that point the FN had been an unrepresented and unthreatening minority but Mitterrand’s experiment won Jean-Marie Le Pen’s party 35 parliamentary seats. So it was that a hitherto marginalised and unapologetically racist party was transformed into a legitimate political force. Although the voting system for the National Assembly was soon switched back to the old plurality model, which put the first cohort of FN politicians out on their ears, the genie was out. One could say the story of French politics over the last three decades has been, in large part, that of the mainstream trying—and generally failing—to put the genie back in the bottle.

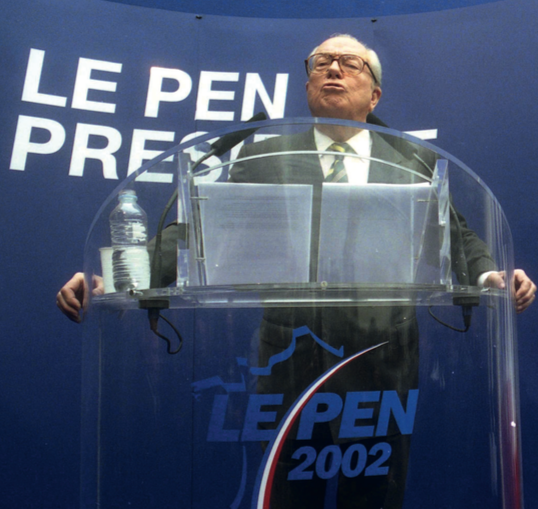

When in 2002 Jean-Marie reached the second round of the presidential elections against the incumbent, Jacques Chirac, I watched with trepidation, then relief, as the “republican pact” kicked in and left and right wing politicians came together and provoked an uplifting show of cross-party solidarity to keep the extremist Le Pen out of power.

That was the first time I saw my own children, Ella and Jack, then 14 and 16, out on the streets. Armed with a banner saying “FN, NON!” they joined an 800,000 strong anti-Le Pen march in Paris. But the fact that nearly 17 per cent of the electorate could vote for him reminded me that the French like to play with fire. In a world where political belief was rapidly disappearing, that felt like no bad thing. The safety barrier would hold.

Fifteen years later the atmosphere is very different—as are the relative strengths of France’s political forces. By April 2016 there were 57,000 paying FN members compared with 86,171 in the Socialist Party (PS), which has lost 40,000 members since 2012. The depressive mood in France is growing and the passion that drove my children onto the streets is hard to imagine today.

French history has always been driven by the confrontation of opposing political families: Jacobins and royalists, Bonapartists and monarchists, moderates and radical republicans, the Popular Front and the nationalist leagues, resistants and collaborators, left and right. Today, to the dismay of pollsters and political analysts, this binary logic no longer functions. Voters swing from left to right and back again and the electoral map is a mosaic of complex allegiances based on obscure and subjective criteria such as whether or not you’re afraid of the future, regret the past or feel comfortable in the present.

There’s no doubt that the depressed mood is partly an expression of the collective trauma of the Islamist attacks of 2015 and 2016. Still under a state of emergency, this nation built on ideals is structurally ill equipped for adversity, for which a pragmatic mind-set is more useful. The emergency regime—which should have ended last July but was prolonged after the truck attack in Nice that killed 84 people on Bastille Day—creates moral discomfort in politicians on left and right. Emergency powers like banning public meetings or the legalising of night-time house searches evoke to some the darkest days of France’s history: Marshall Pétain’s regime and the Algerian War. It was interesting to note how France’s MPs rarely missed an opportunity to criticise the coercion laws proposed by the Manuel Valls government, while voting massively in their favour. Talking the republican talk while walking the authoritarian walk has become the norm. Perhaps, it’s not surprising that a genuine authoritarian can prosper by posing as a plain speaking antidote to the mainstream hypocrites.

Marine Le Pen is such a figure. The youngest of Jean-Marie’s three daughters, she is driven by a redoubtable energy, drawn perhaps from a desire for revenge at a pariah status that dates back to childhood—when she was eight a bomb, meant for her father, blew a hole in the family’s apartment block. Although she qualified as a lawyer at 24, she barely practised and experienced hostility from fellow barristers. It seems that she often protested against her status as Jean-Marie’s daughter, while simultaneously building her career on the defence of FN members and affiliates. This split betrays the complexity of her relationship with her father—one the French media likes to call “oedipal.” In 2011, Jean-Marie handed the reins to his daughter only to be kicked out by her four years later. In a saga worthy of Sophocles, he repudiated her on public radio and tried to make a comeback, but by then she was too powerful. What she was still lacking, though, was her lucky break. For her father it was PR; for Marine it would be terrorism.

Thanatos, the Greek personification of death, is, in post-Freudian thought, the word used for the special lure of despair. Some psychoanalysts argue trauma will trigger one of two competing unconscious drives: Eros, “the life drive,” which controls the libido and strives towards pleasure and survival, and Thanatos, “the death drive,” which unleashes rage or despair and strives towards the destruction of the self or others. The present climate reminds me that the slogan of the French Revolution was initially, Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité ou La Mort. Death was only cut in 1794 in the aftermath of Robespierre’s reign of terror.

Even France’s response to the Nazi invasion of 1940 makes more sense when viewed through the lens of the death drive. It took six weeks for the Wehrmacht to overrun the country, sending millions fleeing from their homes, but perhaps more crucially France’s faith in its own institutions was at its lowest ebb. Paul Reynaud, head of an unstable government, resigned and parliament self-destructed by calling in an angel of death in the form of the “Victor of Verdun,” Marshal Philippe Pétain. Striking a pact with the occupiers, the 84-year-old launched his own “National Revolution,” a four-year anti-parliamentarian regime of terror, bigotry and state-sponsored anti-Semitism.

Le Pen denies she is Pétain’s ideological heir and has worked tirelessly to hide any such sympathies, both in her party’s ranks and its history. She even rejects the extreme-right label for the FN, claiming simply to be “republican.” So skilled has she been at her shape-shifting that she clearly believes she can convince people of anything, including the idea that she is, actually, the rightful heir of de Gaulle.

It happened discreetly, on a beautiful weekend last September at a rally in Fréjus on the south coast where the FN runs the town hall. Le Pen, bronzed and highlighted after a summer holiday on Corsica, subtly appropriated the Gaullist heritage. In a speech laden with Gaullist references she cried: “On our soil are enemies who plan to impose their values on us... French policy is being dictated from abroad, by Brussels, Washington, Berlin! ... What makes us grow is our concern for France... Our concern for la France libre!” Wild cheering.

La France libre was the name for de Gaulle’s government in exile in London, which organised and supported the Resistance. Note how Le Pen chose the definite article—la France libre and not une France libre—making the reference absolutely clear. If you were ever in doubt that this was a rally of the extreme-right, the spontaneous chant that followed would set you straight: “On est chez nous, on est chez nous!” (This is our land).

Le Pen is France’s “angel of death.” Her opponents on the left must know this, at least on a subconscious level. Why else did Socialist nominee, Benoît Hamon choose: “Faire battre le coeur de la France” (Let’s make France’s heart beat); and why did the pro-European liberal Emmanuel Macron choose to name his party, En Marche!, which means “walking” or “marching” as well as “functioning”? As for the slogan chosen by François Fillon, the candidate for the right, “Le courage de la vérité” (Courage of the truth), since he became embroiled in a corruption scandal, it has gone from an uplifting rally cry to a joke.

Despite Le Pen’s plausible, professional exterior and an image of respectability that has been brilliantly achieved over her 23 years in politics—even with the unfavourable legacy of her father—there’s no doubt that a vote for Le Pen will be a manifestation of the unconscious drive towards risky or destructive behaviour. As Hamon rightly predicts, “If she comes to power, it will be a guaranteed firestorm in the banlieue”—the word for “suburb” is now synonymous with “ghetto.”

Although Le Pen proclaims her republican values, a poll in 2015 revealed that 74 per cent of French people still viewed the FN as a party of the extreme right. It builds its central thesis around the idea of France as a nation in decline, blaming “foreign” forces such as immigrants, the European Union, the multinationals or “the banking lobby” (which, although no longer publicly voiced, still evokes to many, as she well knows, the so-called “Jewish lobby” that obsessed her father). Her solution to decline is to “put French people first” thus linking a person’s civic rights to their origin and establishing norms of what it means to be French. Despite this, Le Pen has managed to set the political agenda, which now revolves around her favourite subjects: immigration, security and national identity—for she has learnt to tap into people’s fears and prejudices without even having to name them.

"On our soil are enemies who play to impose their values on us... French policy is being dictated from abroad!"As President, Nicolas Sarkozy tried to do the same thing by making eyes at FN voters during his presidential campaign of 2007. He stoked the flames further in 2009 by calling for a “grand debate” on the question of national identity. “We are proud to have restored an unashamed conversation about national identity,” he said, and “what it means to be French.” Shortly after this, he announced, “the burqa is not welcome in France,” and in 2011 he banned wearing one in public places, with wide cross-party support. In February 2011, strong in the knowledge that 42 per cent of French people now believed Islam was a threat to the nation, Sarkozy launched another “grand debate” on “Islam and secularity.” In 2012, after Le Pen expressed her outrage at state school canteens serving halal meat, Sarkozy called for stricter rules on labelling and confirmed that serving halal food in schools flouted secular values. Sarkozy’s pyromania worked at first, but those voters who are uncomfortable with diversity realised he was not the real thing and votes flowed back to Le Pen.

In her 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt wrote that behind the conventional parties lies “the slumbering majority,” who remain politically invisible so long as there is no serious challenge to the idea that they are, on some level, being represented by the party system. When faith in parliament breaks down, this slumbering mass, Arendt argued, emerges as “one great disorganised, unstructured mass of furious individuals.” A poll taken every year to test the levels of national confidence in political institutions this year revealed that 89 per cent of French people think that politicians “do not take any notice whatsoever of what [people like them] think.” This sense of exclusion and the endless corruption scandals have woken these furious masses and Le Pen—who changed her campaign slogan from “La France apaisée” (France at peace) to “Au nom du peuple” (In the name of the people)—is talking past all the mainstream politicians, straight to them.

Le Pen was already speaking to France’s silent majority in 2009 when she gunned for a former coal-mining town in the north east called Hénin-Beaumont. In an election that year to replace the Socialist mayor who had resigned after a corruption scandal, her party took first place in the first round with 39 per cent of the vote. Her speeches started referring to “France’s forgotten ones” or “France’s invisible ones,” and two years later the town—in a region where unemployment hovers at 13 per cent, three points above the national average—fell to the FN.

Le Pen knows there is a rich seam of untapped despair, legions of potential supporters ignored by mainstream politicians: “neutral, politically indifferent people,” wrote Arendt, “who never join a party and hardly ever go to the polls.” In a way, Le Pen is telling the truth when she says she is neither left nor right. Her target voters are demoralised individuals who do not like the world as it is. And if they are not yet demoralised, she will make them so.

One of Le Pen’s most effective techniques has been to harness the doctrine of “tous pourris,” (they’re all rotten). Borrowed from Coluche, France’s most popular comedian, the idea that politicians are intrinsically immoral no longer makes the French laugh. Increasingly, it makes them vote Le Pen. Financial scandals among the political classes help the contagion of despair but this is another miracle of Le Pen’s brand: she is still perceived as relatively clean, despite investigations for tax evasion and fraud. In 2013 a fraud case was brought against “Jeanne,” the micro-party that was set up by her entourage in 2011 to fund her presidential campaign. The police now wish to question Le Pen on a case involving her chief of staff and a fictional employment contract with the European Parliament (EP).

Le Pen’s reaction is to call the investigation “a political cabal” and refuse to show up for questioning by the French judiciary police. It is a measure of just how untouchable she feels and how effectively she has eroded, not only the moral credibility of all things European, but also the reputation of the judiciary, that she’s getting away with it. The Socialist prime minister, Bernard Cazeneuve, has said that if she wishes to hold the highest office Le Pen “cannot place herself above the laws of the Republic... No political leader can refuse, if they are a republican, to answer a judicial summons.” But it seems she can, for as most people know, Le Pen is only a republican when it suits her.

For a people brought up to venerate ideas, loss of faith in politics is traumatic. The despair is not confined to those tempted by Le Pen. My own family’s tangled voting intentions offer a good illustration of this discontent. Jack, now 31, and Ella, 29, are both approaching this election from a place of disenchantment. Jack, who in the 2012 runoff between Sarkozy and Hollande, put in a blank vote for want of any decent option, will in the first round pick Hamon on his green credentials, and in the second round vote for anyone but Le Pen. Ella, who voted socialist in 2012, will vote in the first round for the untried 39-year-old former banker Emmanuel Macron, and then in the second round go for anyone but Le Pen. They both believe that a victory for Le Pen is possible. So does their father Laurent, who has always, until now, had faith in the republican pact. To reduce Le Pen’s chances of victory, Laurent, who voted socialist last time, had initially planned to vote for Francois Fillon. That was before it was revealed that Fillon’s wife allegedly received €600,000 of public money for a parliamentary assistant job for which she appears to have barely shown up. Laurent will now vote, without enthusiasm, for Macron as the strongest anti-Le Pen force.

Along with 75 per cent of the nation, Laurent is disgusted by Fillon and wants him to stand down but Fillon, who had previously sold himself as the campaign’s honnête homme, now seems to be taking a leaf out of Le Pen’s book, not only by refusing to resign but by disparaging the justice system and calling the case against him “a political assassination.” This is all the more devastating for people like Laurent who were taken in by Fillon’s incorruptible image and believed in his “covenant of sincerity and honesty” with the French people. At a dinner party in February, Laurent heard someone saying that he felt so angry about Fillon’s behaviour that he’d probably vote for Le Pen if Fillon were in the second round with her. Five years ago, I would not have believed anyone in this circle of bourgeois liberals capable of thinking such a thing, let alone saying it out loud.

If that electoral crash barrier were going to fail, this could be the year. Why? Because thanks to the success of Le Pen’s message, voting instructions given by mainstream politicians are more likely to be ignored. Because the “republican pact” is no longer universally perceived as a rampart against extremism but has become, for many, the undemocratic manoeuvring of a political elite. Because this same pact may reinforce Le Pen’s status as an outsider. Because this faux union of opposing political families to keep her out of power also fuels her narrative for France as divided into two groups: the privileged few in favour of globalisation and the once silent, now furious masses who are against it, a strategy that not only masks her party’s extreme-right tendencies but feeds the despair on which she depends.