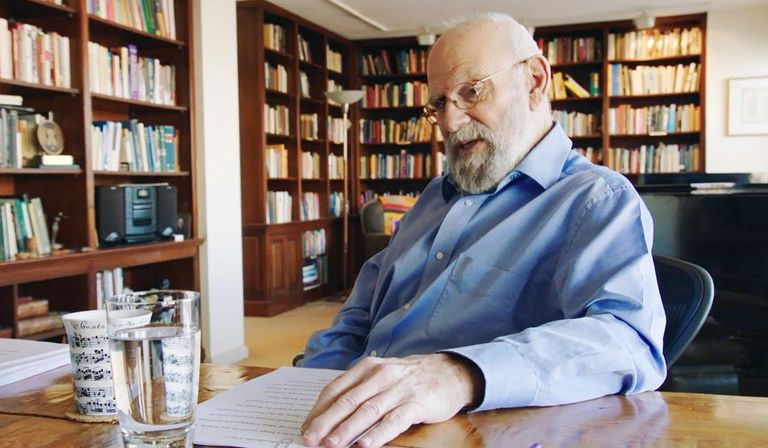

Oliver Sacks was sipping tea, juggling a cookie, his knees together, his fumbling hands making him seem unsure and a bit hunted, like Edward Lear—the same Socratic beard, the same gaze, twinkling with myopia. Oliver also looked lost, like a big, befuddled and bearded boy.

His bumbling is not an act. He really is near-sighted and cack-handed. At the cash register in a coffee shop, he fiddles helplessly, his thick fingers futile and unresponsive in his purse. He constantly loses things. He is hesitant and forgetful; in his dreamiest and perhaps most intellectually productive moods he stumbles and trips. He has fallen on his face many times and sustained serious injuries. He wrote a whole book, A Leg to Stand On, about one bad stumble, which resulted in a severe leg injury.

But once in the water he never falters. He is happiest in the water, distance swimming, snorkeling, diving. He is a porpoise, and I have swum with him in the dankest waters of Lewis Bay in Hyannis and Waimea Bay in Hawaii. He is a strong and agile swimmer and stays in the water for a long time. "It takes 40 minutes in the water just to warm up, and then the real swimming starts."

He says he is happiest among invertebrates, among cephalopods; among plants-ferns and cycads. One of his dreams is to swim in the so-called Jellyfish Lake on one of the Rock Islands of Palau, in the Western Pacific. I described to Oliver how I had swum there myself; the water was thick and yellowish, a stew of jellyfish, some like parasols and some like nightcaps. They had no sting but they bulged with gelatinous ectoplasm and filled the small volcanic pool; my whole body was pressed at each stroke by the strongest wobble of slime. I did it on a dare and was glad finally to pull myself out of the water. Oliver said there was nothing he relished more than spending a whole day swimming among the millions of jellyfish.

On dry land, fluctuating temperatures make him irritable. He complains if the temperature inside or out does not hover around 65 degrees, and he has been known to carry a foot-long thermometer into restaurants, especially in the summer, to establish whether the dining experience will be a comfortable one. He cannot cook. But he is not fussy about food, indeed he dislikes culinary variety—one of his unshakable habits is to eat the same meal every day. A large pot of the stuff is prepared for him at the weekend, and he warms up portions of it through the week. He is not odd in this; as Oliver points out, most of the world's people eat the same meals every day.

He spends part of the week at his wooden bungalow on City Island in New York, which he bought in the 1980s for its nearness to swimming and his hospitals. The house is crammed with books; apart from books, Oliver says, "I own nothing of value." The rest of the week he spends in Greenwich Village at what only can be described as Sacks Central: both a comfortable apartment and an efficient office. Oliver types swiftly with two fingers on a old manual typewriter, but in his office he has access to every modern innovation—machines, computers, databases—and also Kate Edgar—assistant, minder, amanuensis and friend, and midwife to his last five books.

Like many people with active minds, he is a bad enough sleeper to rank as an insomniac. He is tall, powerfully built from daily swimming; he is physically strong (he once held a California weightlifting record, doing a full squat with 600 pounds); but, aged 65, he also carries on his body the bumps, scars and stitch-marks of his mishaps.

A writer's life is almost unapproachable except through the writing, which is inevitably full of ambiguities. You spend time with a writer and you get—what?—wool-gathering silences, rants, evasions, the contents of a cracker barrel; most such visits are just excursions into tendentiousness. But if the writer happens also to be a doctor there is a visible human dimension which can be seized: Voltaire squeezing leeches on to a patient's skin; Chekhov poking someone's tonsils; Freud questioning the hysterical Anna A; William Carlos Williams delivering a baby.

Oliver Sacks's neurological writings have been praised by no less a stylist than WH Auden. But Oliver the doctor was the person I wanted to know better: Oliver in a ward, Oliver making a house call, Oliver on the street, in the world, observing; especially Oliver in New York, treating patients. It is obvious from his writing that "patients" is a misleading word for the people he writes about: they are his friends, some of them as dear as family members.

Oliver is at ease working in the hospital, but he is sometimes wary, even there. He fears that he might become very flustered one day at a hospital and because of his stammering and shyness be mistaken for a patient and locked up.

It is the nightmare of Chekhov's Ward Number 6, a story Oliver often refers to, in which the doctor, Andrei Yefimich Ragin, is mistaken for a mental patient and is unable to talk his way out of the ward. He is beaten by a brutish watchman while other doctors smile at the poor doctor's protestations. One of the characteristics of a strong protest is that it sounds delusional and paranoid. "I must go out!" he cries. He is told to shut up. He is beaten repeatedly. At last the doctor dies in his own hospital.

A cruel variation on this story is the one Oliver tells about the former medical director of a New York hospital who had retired. Three years later the doctor was admitted to the same hospital with symptoms of an advancing dementia. One day, returning to his old habits, he slipped into his white coat and went to his old office to scrutinise the patients' charts. Over one complex chart he muttered, "Poor bugger," then closed it up and saw his own name on the file.

He exclaimed, "My God!" and turned ashen. He started shaking and crying in horror. In that terrible lucid moment he saw it all. "It was one of the most awful things I have ever seen. He was devastated. Ultimately he became profoundly demented," Oliver said, finishing his story with a grim sense that one of the paradoxes of neurology is that there is not always a clear distinction between sanity and madness—one often resembles the other, transformation is constant; many people in the hospital could function on the street, many people on the street are demented.

***

Oliver's parents, Samuel and Elise Sacks, were physicians and, like Oliver, "medical storytellers"—seeing their patients as long-standing friends with complex histories. Elise's father had 18 children and there were nearly 100 first cousins. Abba Eban is Oliver's cousin; so was the cartoonist Al Capp.

Oliver, the youngest of four boys, was a lonely member of this vast extended family. At the onset of the Blitz, in 1939, he was sent out of London for safety reasons. He was six. It was a four-year ordeal of separation. He went to a boarding house in Bournemouth and then was moved near to Northampton. He experienced cruelty, discomfort and the wintry mendacity of authority figures. This period could have destroyed him. It certainly marked him, as the Blacking Factory marked Dickens, and the House of Desolation marked Kipling. It also resembles the rustication recounted by Orwell in Such, Such Were the Joys.

"I became obsessed with numbers, as the only things I could trust," Oliver says. He was reassured by the periodic table, seeing "order and harmony in the family of elements." By wounding him, the experience made him the sort of scientist who is brother to the poet.

In his childhood attachment to the periodic table, to colours, to metals, to science and solitude, he related to Humphry Davy, a kindred soul. As a university undergraduate in the late 1950s, Oliver experienced England's first postwar sparkle—the Angry Young Men, the Goons and Beyond the Fringe. Jonathan Miller, an embodiment of that period's humour and intelligence, is one of his closest friends. Oliver came to California just as America was being energised. He was 27 and living in San Francisco in the early 1960s. He dabbled in hallucinogenic drugs. But his "druggy excitements" ended on the last day of 1965, when he looked into a mirror, saw his skeletal self and thought, "unless you stop you will not see another new year."

He stopped, but he stayed in California for five years—years of medical residence and reading; years of experiment; motorcycle years. Then he left for New York, where he devoted much of 1966 to the study of earthworms at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx: he gathered worms by the thousand to extract myelia from their nerve cords, an episode which was inflated in the movie Awakenings.

In October 1966, he arrived at Beth Abraham Hospital. There he has remained for 32 years, earning the New York rate of $12 for every patient he sees. This hospital, the "Mount Carmel" of Awakenings, is in the Bronx, an hour or so by subway from midtown Manhattan. It was once a charity hospital. The patients here and at the homes of the Little Sisters of the Poor not far away, where Oliver has been working since 1972, are generally older men and women.

Over the decades that Oliver has spent caring for these people, he has seen them age, sometimes showing improvements, sometimes regressing. Many are in a kind of suspension. One brain-damaged man said to Oliver: "I've recovered enough to know that I'll never recover enough." Another man is immobilised in a chair. He was mugged in Manhattan in 1986, when he was 22, and received severe head injuries which put him in a coma. After being treated in acute hospitals he improved a little. But now he is just sitting, a wounded man; conscious of his condition.

"Agnes is our senior centenarian," Oliver says, smiling at a bright-eyed woman in a wheelchair. "Twenty years ago she chased me up four flights of stairs, vociferating. She was Parkinsonian. Violently, writhingly choreac"—Oliver has a habit, when using an expression such as "writhingly choreac" of giving an imitation of the affliction—"Yes, I was frightened."

One day at Beth Abraham Oliver showed me a patient's thick record. This was Grace, also Parkinsonian. It was written in her file: "An enigma since 1929." Hers was a static neurological condition: writhing movements, tics, oscillation of the eyes. She was on no medication, because one of Oliver's dictums is: "Ask not what disease the person has, but rather what person the disease has."

Oliver observed that Grace felt an energy with her condition. "With medication she would have devitalised." Her husband had been very important to her. Grace had said: "I have the drive, he has the patience. We make a good pair." A note Oliver had made in her record read: "I cannot avoid the feeling that she is preparing for her death." Grace died two months later.

Without the dullness induced by medication, a Parkinsonian patient has the energy to react, to "borrow" postures or gestures from other people. Sometimes people are rigid until they see a friend, or an animal or a pattern; until they hear music or are asked to go out for bagels. Such patients, seemingly comatose or indifferent, react when they see Oliver. They smile, they widen their eyes. In many cases the first reaction of a patient is to reach out and touch him—he returns the touch, which is almost a caress.

"Here is our senior resident," Oliver says. "Hello, Horace"—and he clutches the man, who smiles shyly and says, "Doctor Sacks." Oliver holds his hand and speaks to him directly, softly, inquiring how he is. Horace smiles. His arms and legs are stick-like, his fingers are twisted. He has a wan smile of innocence and sadness. Horace has never walked. He has had cerebral palsy since birth. He was admitted in 1948, when he was 23. At the time he was selling newspapers in Times Square. He was a familiar sight on the corner of 42nd Street. American cities then were full of such newspaper vendors. He could sell papers, he could move his arms, he could speak and give change. Like many patients he had been looked after in the outside world, but when he ceased to get help he was sent to Beth Abraham. He has been there for 50 years now, staring out of the window. "He is rather sad now," Oliver said. "Horace was very attached to another patient, Ruth." They sat side by side in their wheelchairs, holding hands. They ate together. "Since Ruth died he has deteriorated. He has lost his goals."

Another day at Beth Abraham, Oliver and I were getting into the elevator when a woman wheeled herself at the opening, propelling herself towards the door, her left leg sticking straight out, like a sort of weapon. Her hair was tangled, she was old and energetic and angry. "You fucking bastards!" she screamed at us. "You bastards! Let me on the elevator! I want to get on! Let me fucking on! Fuck you!"

The door shut on the woman's howling. Everyone in the elevator was rattled except Oliver, who said softly, "I think I recognise her. Didn't she used to be on the second floor? Ruth something?" A person's anger does not make Oliver angry: it appears to calm him and makes him more watchful, because rage is a symptom, like a tic or a gesture.

At the Little Sisters of the Poor Hospital we met Janet, a paranoid woman, who had been violent. Before Janet entered, the nurse gave Oliver the woman's records. "She thinks there are men attacking her," the nurse said. "Men trying to rape her. She reported the priest and a workman—and I can tell you there was absolutely nothing in it. She's yelling and screaming."

Janet was about 70, with bulging thyroidal eyes and yellowy white hair in a young girl's page-boy cut, neatly dressed in slacks. Her puffy, almost-coquettish face looked like Bette Davis's, playing Baby Jane. She was eager to see Oliver; she had been waiting for his visit.

"Janet? How are you doing, Janet?" Oliver asked.

"There are a couple of men here who are bothering me," Janet said, smiling at me. "One of them is frightening me to death. Following me!"

"Yes?" Oliver said. "What did he say?"

The woman began to protest. "I am a decent woman. I was raised in Greenwich Village by a good Irish family." She said loudly, "It wasn't as though I was wearing a bikini!"

"You said there were two men," Oliver said.

"There's a Catholic brother—his shirt sticks out like it's a penis," Janet said. "He's staring and looking at me. This is a Catholic holy place! I dress modestly. I go to my room at about ten. I was sleeping alone—I have to mention that I have never married. All of a sudden I hear a banging on my room! I was afraid. After a while I look out. No one there, but I saw Julia across the hall. She said, 'It was the brother.'"

She said this looking at Oliver and me with popping eyes, smiling, smoothing the thighs of her slacks. She made Oliver promise to return soon, winked at me and left. "Notice the erotic content in what she said," Oliver said. "'I sleep alone.' The mention of the bikini. The priest's shirt like a penis."

The nurse told Oliver: "I forgot to tell you that when she is in her room she goes about stark naked. She answers the door without a stitch on. Just stands in the doorway, naked."

"Paranoia and eroticism often go together," Oliver said, making a note in the file.

"This woman can't speak, but she can sing," Oliver said, as another smiling woman propelled her wheelchair towards him. He introduced me to Jane and her music therapist, Connie Tomaino.

Jane smiled, clutched Oliver's hand, hugged his arm, but said nothing. Oliver, who cannot sing, tries to compensate by becoming a conductor. This does not always work. I could not accommodate him when, introducing me to a song-responsive patient, he asked me to sing something by The Grateful Dead.

Connie began to sing, What a friend we have in Jesus. Jane found her voice and joined the hymn. She became livelier, her facial expressions became friendly. When the hymn ended she entered a sort of blankness.

Jane was aphasic. She could utter one word, "fine," in conversation, but the rest was what a neurologist would describe as memory deficits. She could sing fluently. Connie has found in her work over the past 20 years that memories aren't really lost, at least with apparent aphasia or dementia. What is lost or damaged is the ability to access these memories. "What music can do, or at least music that is familiar, is tap into those memories or unleash them," she says.

I asked her whether music treatment can affect Parkinson's patients. "Yes," Connie said. "In the case of Parkinson's it works as 'rhythmic cueing'—people sometimes get out of their chairs and start dancing."

Oliver added: "People with Alzheimer's are still able to play music very well. Why is one ability preserved and another lost? There are people who are too drunk to stand but can dance well, and when the music stops they fall down."

***

Oliver's "street neurology" was something I had longed to see ever since I had read about it in "The Possessed" chapter of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. The phrase refers to the assessment of a person's condition after observing that person in a casual setting—the street, a bus, a movie line, a room full of strangers. I suggested that we walk around New York and just look at the people on the sidewalks—limping, twitching, "vocalising." To an outsider, New York seems populated by people on the verge of a nervous breakdown; and a New York nutter seems to me world-class. Was this something to do with the way the city—so cellular, so like an asylum, an island of vertical compartments—isolates people and intensifies psychosis? Oliver might have the answer.

He liked the idea of street neurology, but it would have to be short—his foot was bothering him."I'd like to show you two people, one with Parkinson's and one with Tourette's. They are both artists," he said.

Oliver has known Ed Weinberger, a furniture designer, for 15 years. He has never written about him. As with many people in Oliver's life, there is no clear distinction between friendship and treatment. These people are part of his life—perhaps the largest part of his life. Ed lives on the eighth floor of a building on the Upper West Side. When he answered the door he was canted over—he has Parkinson's. Oliver stepped aside and said almost nothing. It was what I had noticed at the hospital, a sort of group dynamic in which no one is a patient, no one is in charge.

Oliver does not speak of cures; his genius lies in his understanding of patients, and the realisation that a person's handicap often causes the discovery of hidden assets. Faced with a patient who has a severe neurological problem, Oliver is open to anything: aromatherapy, music therapy, group therapy, acupuncture, hugging, hand-holding, fresh air-and of course drugs, although Oliver says that they often obscure the real cause of a problem and create misleading symptoms of their own. He wants to go beneath the symptoms to find the problem and treat it. Because this takes so much time, Oliver offers more hours to his patients than any other doctor I know, which perhaps explains why his medical earnings last year were $7,000—a figure reduced to zero after he paid his malpractice insurance.

Oliver has said that his shyness—possibly caused by the wartime separations from his family—is a sort of disease. Shyness plays a part in his observation, giving him a vantage point. It makes him patient, compassionate and tolerant. Oliver has a capacity for seeing abilities where another doctor would see only deficits.

For the first half hour or so at Ed's, Oliver hardly spoke. He did not want to intrude; he wanted me to form my own impressions. I soon saw that Ed's leaning was echoed in the furniture. In every table or chair, in desks and shelves, angles had been cut out of their surfaces, the corners were bisected, the legs seemed to lean. Everything stood solid—the more solid for the way the angles supported them.

"Look at this." It was a photograph of Ed crouched on a legless corner of a table that seemed to defy gravity. Ed was a collector of well-made objects-old cameras, spyglasses, telescopes, Chinese jades and bronzes. He also had a vintage car, a 1948 Bristol, made in England.

"That's a lovely desk," I said.

"I call it my 'bridge desk.'"

Arched like an eyebrow, it was an unusual wooden desk; mellowpale orange pearwood, sanded by hand, the details of grain matching the joinery, very carefully chosen, giving the illusion of lightness. The legs were splayed, somewhat like Ed's own. The cantilever legs, he said, were based on a bridge designed by Robert Maillart. Maillart was a Swiss bridge engineer who revolutionised the designing of bridges, making them stronger and more slender, combining the whole-arch, girder and road-into one piece.

Many pieces of furniture in the room looked as though they were about to topple over. Ed said it was all a trick of the eye. He showed me a red desk with jutting planes and said that he had derived some of it from a Kwakiutl Indian mask. "I wanted to give it the illusion of an extruded form."

Needing his life to be angular, he completely redesigned the furniture in his house; in so doing, he contrived to invent a totally new sort of furniture, a Parkinsonian-style, which was a way of standing and living. What another person might take to be an obstacle had given him a new conception of furniture.

"Ed's passionate about cars," said Oliver. "I used to ride motorbikes myself-Nortons." Oliver recalled that when he was doing his residency at UCLA, there was a quadriplegic woman who said she wanted to go for a ride with him. Oliver knew that the woman did not have long to live. "I thought I would grant her this wish," Oliver said, "and so my friends helped me get her on the back of the bike. They wrapped her up, tied her firmly on the seat, and off we went. She loved it. We all rode together, about six or eight motorbikes—the quadriplegic woman on the back of mine."

"We returned to face an aghast and curious crowd," he said, and seemed to still see the crowd of astonished faces and the untying of the quadriplegic woman from the pillion seat. "As far as the department was concerned, I was somewhere between an embarrassment and an ornament," Oliver recalled.

The puzzled response of Oliver's department was to be repeated later, in 1991, when he was let go after 24 years at the Bronx Psychiatric Center. The director was quoted in the New York Times as saying: "Dr Sacks was not considered particularly unique here. I am not sure he complied with state regulations."

At the mention of hospitals, Ed described various horrific experiences he had had about four years before, when, heavily sedated, he had had a severe nervous reaction and hallucinations. From being a patient with Parkinson's he was diagnosed as psychotic. He had to be restrained by male nurses. He was treated as someone who was out of his mind.

"I was really crazy. The food was a problem, too. If you have Parkinson's it's hard to swallow. They gave me rough food, not soft food. That could have choked me. I said, 'You should give me soft food,' but they paid no attention. I spat it out. They thought that was very amusing." One day he overheard them saying that, although his condition was pretty bad, they wanted to go on giving him this dangerous medication in order to finish their experiment. This enraged Ed. "I called my own neurologist and told him to get me out of there or I would sue him. That's what did it. The next day I was out of the hospital."

"I come across many people who have been in hospitals for 20 or 30 years because of being misdiagnosed," Oliver said. It was the old horror from Ward Number 6. "There are forms of these so-called designer drugs which render people profoundly Parkinsonian. Deaf people are mistakenly diagnosed as retarded. Post-encephalitics are sometimes locked up in mental hospitals as schizophrenics."

An operation called a pallidotomy had saved Ed. He had opted for the operation because of the terror of hospitalisation and his severe Parkinson's, which at times had given him episodes—some as many as six hours long—of utter immobility. But the operation had been risky. It was brain surgery which involved targeting a precise area in the brain and destroying it. Risks of intellectual and speech impairment arise from locating the target area. But the procedure worked—Ed was liberated. Before the operation he had been immobile: he could not walk, talk or get up from his chair.

"I have been reborn," Ed said. "I have a new life." It seemed to me that Oliver's friendship and insight was as essential to Ed's understanding as the surgeon's knife. Ed's ambition was to fly to England, pick up a new Bristol—the angular car for the angular man—and drive to Switzerland, to look at the gravity-defying angles of Maillart's bridges.

***

Street neurology, Oliver said, allowed "the spur and play of every impulse." The true test of this was accompanying a very ticcy Touretter through New York (Tourette's syndrome involves various forms of involuntary behaviour, including compulsive imitation of others). Shane F, who is mentioned in passing in An Anthropologist on Mars, happened to be visiting New York from Toronto; Oliver suggested that the three of us go to the Natural History Museum. In Shane, Oliver said, I would see "Tourette's as a disease. As a mode of being. As a mode of inquiry."

When we met Shane in front of the hotel on 81st Street, he rushed to Oliver, hugged him, touched his face and became excited, vocalising an urgent and eloquent grunt, "Euh! Euh!" as he described an auto accident he had just witnessed. "But some people came up to help!" Shane said in his hurried, stuttery way, like a child trying to discharge a whole thought and stumped by syntax in his excitement. He went on describing the accident, and from that first moment he dominated us. Also from that moment Oliver seemed to withdraw. He was a presence, no more than that, sometimes a shadow, sometimes a voice, always a friend; and often his figure—protective, yet entirely unintrusive—was like that of an ideal parent.

Shane was 34 but seemed younger because of his explosive gestures, great energy and eagerness. He had black hair and bright eyes; he was handsome and vital, humorous and talkative, too impatient to wait for an answer. He did an imitation of President Clinton, then one of Oliver. He caught the Englishness and the slight stammer in Oliver's voice. When Shane was mimicking someone's voice or accent he was so concentrated that he ceased to be Tourettic.

We crossed the street and Shane took off, without a farewell. He shot down the sidewalk, sprinting towards the Natural History Museum like a Bushman through tall grass, very fast, his arms pumping.

"Imagine Shane in space," Oliver said, watching him with pride. "One violent movement and he would push the shuttle off course." Several times he mentioned, with genuine amusement, the possibility of highly sophisticated technology upset or destroyed by such tics or flailings.

Seventy-eighth Street seemed the perfect place for a Touretter. Shane smelled a lamp post, gripped it and swung around it. He moved on, touching posts, stooping to touch the curbstone, the sidewalk, the parking meters. Then he sniffed the parking meters. He rushed back. He touched both my elbows, then Oliver's, dashed on ahead again, found some more parking meters to sniff and ran on. Now I knew why the heels of his boots were so worn.

"Why does he touch those posts?" Oliver was implacable. "Ask him," he said. Shane smiled at my question. He said: "You're looking for a rational reason. Euh! Euh! But if I told you would you believe me? Would you think I was telling you the truth? I touch them because they're down there, this one and then that one." He twisted his head and grunted again. "Is the reason I gave you the right reason?"

Soon he was moving too fast for me to keep up with him and persist in my questions. Oliver just smiled. On this June afternoon, a cool day after days of heat, people were strolling, but few of them noticed Shane. This was New York City. Shane did not seem unusual; he did not stand out in the crowd. Odd and ticcy as his behaviour was, it was not more extraordinary than that of the gigglers and shouters, the roller-bladers, the youths with hats on backwards carrying boom-boxes, the woman pushing a supermarket trolley crammed with plastic bags, the two haggard men sharing a bottle wrapped in brown paper, the screeching girls, the murmuring old men. He waited for the Walk sign, he jeered at the bad drivers, and when the light changed and we walked across Columbus Avenue, Shane was running, stopping to touch the low stone walls of the museum, or the gate posts or the trees. Now and then he hugged a tree and sniffed it, pressing his face against it.

"He remembers everything," Oliver says. "Everything he touches. Everything he smells."

Shane seemed like someone making a new map of the city-his own map, on which every object had a unique shape, temperature, smell and texture. In his Manhattan, every parking meter was different. There was no such thing as "a parking meter." There was only, say, "The sixth parking meter on the north side of West 78th Street, east of Columbus Avenue—like Funes in the Borges story, "Funes the Memorious," who can't understand why the word "dog" stands for so many shapes and forms of the animal; moreover, it bothered him that the dog at 3.14pm (seen from the side) should have the same name as the dog at 3.15pm (seen from the front).

Shane ran on, calling out, "Hup! Hup! Hup!" A white dog on a leash sensed Shane's hurrying, became agitated and leaped into its mistress's lap. No one else paid much attention, but the dog reacted to him as though to another creature—not as a threat but as something large and alive with whom it would have to share its space. The dog began barking—not at Shane but in a generally upset and distracted way. Shane laughed, and replied with his own "Euh! Euh!"

So far, in terms of street neurology, it seemed that a world-class Tourettic was just about invisible on a New York sidewalk except to a small dog. "Sometimes Shane creates misunderstandings," Oliver said. "And occasionally they are serious misunderstandings. But usually it is no worse than this."

We entered the Natural History Museum. I bought the tickets, Shane barked and coughed and chattered, and smelled the turnstile as he went through it. He pinched Oliver, he touched walls and doorways, he ran his fingers over plaques, he moved rapidly from one exhibit to the other. He drew a long breath and seemed to inhale everything he saw. Then he said, "Let's sit down and take a good look," as though willing himself to be still.

We sat in front of the scene of rural winter, a cross-section of the countryside. Dead leaves on the ground, mulch below that, rodent tunnels and rotting vegetation. The sight of decay launched Shane into a frenzied description of the movie—his favourite—Soylent Green, with its prophetic visions of a dying planet: ozone depletion, dead oceans and overpopulation. This explanation calmed him a little; then he said he wanted to see the tigers. We found three stuffed tigers in a glass-fronted exhibit.

Knowing that Shane is an artist—judging from some of the paintings Oliver had shown me, a very good artist—I asked him: "What do you see?"

"This is meant to inspire nobody. It doesn't inspire fear or awe. This is a base comparison to the real thing. Euh! Euh! This is a mausoleum-like glass enclosure, sort of pathetic. It's like a memory, the ghost of ghost. It doesn't make sense. Why don't they stuff humans and put them in here? You know, the tiger in life can stand very still. A tiger can stand breathless and frozen. As Oliver would say," and here he slipped into Oliver's donnish accent again, "'It's Parkinsonian... It's... It's lithic...' But these tigers have only the shape and the memory, but not the lithe movements. They're not infused with life. A sculpture would be better."

I asked Shane about his family.

"My father's Jewish. My mother's crazy." He tapped my notepad. "Put down Canadian."

He began pacing again.

A thin leathery-faced Indian man approached Oliver. He woggled his head and said: "I heard you speak in Rotterdam."

"Yes?" Oliver said.

The Indian said: "Do you remember my question?"

Oliver stepped backward and took a better look at the man. The Indian said, "About Tourette's. Can it manifest itself at an elderly age?"

"Oh, yes," Oliver said. "But I can't remember what I told you. Not long ago, I met a woman who was 58. Her Tourette's manifested itself when she was 52."

"Oliver, Oliver, Oliver, Oliver," Shane was chanting, and grunting, too. He was calling Oliver's attention to a pair of dinosaur skeletons. Shane then began to imitate the movements of each creature—the leaping Allosaurus, the roaring Diplodoccus.

Nearby, a man was making a charcoal sketch of the Allosaurus on a large drawing pad—the pad was four feet by three. Some people were sitting on benches, lovers were holding hands, kids were squalling. Shane paced up and down, making dinosaur faces, dinosaur gestures. He approached the man sketching and began commenting on his picture. The man listened. Shane asked for a piece of paper. Without a murmur, the man tore off a large piece.

"Newsprint," Shane said, and twitched violently. "It's not good quality."

With a mixture of charm and chutzpah, and uttering sudden sounds, he put his hand out. I thought the man was going to hit him. The man gave him a piece of charcoal. Shane threw the piece of paper on to the floor, and crouched on it, poised like the attacking Allosaurus. He began sketching rapidly.

Oliver had been pacing—not impatiently—merely, it seemed, to get some sort of perspective. I approached him. He told me: "I have never seen him do this before." Oliver slipped away. I drifted over to Shane—as, I suppose, Oliver thought I might. The next time I looked up, I saw that Oliver was looking at Shane and me. In pursuit of street neurology I had believed that I would be observing Oliver, and of course I had, to an extent. But Oliver was elusive; he evaded my glance, he stepped out of sight or stayed firmly in the background. He listened, he let others talk and only when they were done did he put his oar in.

Some people gathered to watch Shane swiping at his sketch, ignoring the man who was slowly scraping away on his pad. In minutes, Shane was done. "The gesture, the gesture, see? Hup! Hup!" Shane said. "The whole movement, euh!"

Shane dropped the picture and began pacing rapidly again, vocalising; he had been still throughout the making of his sketch. I picked up the sketch and brought it over to Oliver, who said: "One wonders to what extent these highly gifted people's imaginations may be flavoured by the gesture—the movement. It immediately seizes and is seized. Some of Shane's pictures are of animals in motion. But there are also some highly symbolic ones, about starvation, exile, torture."

Shane's picture was amazing for its speed of execution and its accuracy. It was the Allosaurus in motion; even the other artist approved; so did the passers-by. We left the museum. Shane sprinted, Hup! Hup! Hup! and vaulted a planter by a doorway. He called to Oliver: "You do it!" Oliver said in a self-mocking Edward Lear-like way: "I am an elderly gentleman and can't be expected to do that."

We went to a cafe. Oliver seemed baffled by the menu. He stammered and then decided on tea. Shane ordered tea, too, but talked so energetically that he did not drink it. He talked about Robin Williams, Lenny Bruce, ecology, deforestation, floods, dumping raw waste, tourists, Aids in Thailand, the Galapagos, Victorian science and coprolalia.

"Sometimes in Tourette's there's coprolalia-compulsive swearing. I don't have coprolalia, except sometimes, when I'm alone," Shane said. "When I'm painting, then sometimes I swear and I swear when I have touching tics. I touch my bed. My comments usually involve my family."

"In the eight years I've known you I really haven't heard this," Oliver said. "Only 10 or 15 per cent of Tourette's patients have it. Some people have severe motor tics, but no coprolalia."

Out of the cafe Shane sprinted ahead and began talking loudly, chattering to people on the sidewalk. A young woman smiled at him. She was about 23 or 24, in cut-off jeans and a blue patterned bandana.

"Hi, hi, hi," Shane said.

"I know you," the woman said.

"Hi, hi, hi," Shane said.

"You're famous, aren't you?" the woman said as she beamed at him.

Shane was vocalising—barking and coughing. He touched her elbow very gently. She took his hand and they started down the sidewalk together, holding hands. Shane then sprinted with her, hurrying her forward. As though energised by him, the woman laughed excitedly.

Behind me, Oliver said, "The car's up here," and pointed in the opposite direction.

Seeing Oliver standing so calmly, I saw again, as I had seen in the museum, that he was helping me get to know the process of approaching neuro-history by setting up these meetings. But they served him, too, by offering him contrasts, and different points of view. I understood, then, that at the hospitals, with his friends, in the street, and now at the end of the day, it had always been part of his intention to observe me; and more, to see the interplay between the person and me—the aphasic, the choreac, the paranoid, the Parkinsonian, the Touretter. It was street neurology in the widest sense, because I was not the only observer; I was part of it, an actor in the psychodrama.

In Oliver's view, human behaviour is prismatic, multi-layered, and his life and work shows that revelations came over time. In this natural neurology, personality was not painted in primary colours; rather it was shown in a million subtler hues, delicately shaded; as Oliver had written in another context, "a polyphony of brightnesses." A solitary person was monochromatic. When others were present, the personality was suffused with colour. I remembered something that Oliver had said about a man at Beth Abraham, whom a doctor might term a vegetable. Oliver had spent decades treating him. True, the man was confined to a wheelchair but—the phrase stayed with me—"He is emotionally complete."

Oliver was looking past me, in the direction of Shane. "I'll get him," I said. But I could not see Shane.

Shane and the young woman had gone two blocks before I caught up with them. It was only because they had been blocked by traffic that I caught them at all. Shane could easily have hurried the woman away. She looked as though she wanted to be hurried away.

To this young fresh-faced New Yorker, Shane was not a Tourette's sufferer, nor ticcy, nor gesticulating wildly, nor hurrying up and down in an inexplicable manner. He was another New Yorker, an energetic young man, talking fast, stammering, grunting. He wore a black jacket and cowboy boots. Had the young woman looked, she would have seen that in an afternoon of sprinting through streets and museum corridors the heels of the boots had been worn flat. One person had been frightened by Shane-a woman with a baby. A few people had smiled at him. Only the dog had been spooked.

This young woman was madly attracted, and she scowled at me when I approached and spoke to Shane. "We have to go," I said. "Oliver's way down there, waiting for us."

"Shane, who's this guy?"

After a two-block sprint she was already on a first-name basis with him.

"I have to go," Shane said. "Dr Oliver Sacks. Down there! Euh! Euh!"

"You're famous, aren't you?" she said to Shane. "I know you are. Don't go."

"Euh! Euh!" Shane was trying to speak. "Give me your number. I'll give you a call."

The young woman screeched with pleasure-she was laughing, eager, expectant.

"If you blow in my ear," she said and laughed some more. Shane blew lightly into her ear as she wrote her name and her telephone number on Shane's Natural History Museum brochure.

"Do it more! Oh, that's nice!" Then she hugged him. "Call me Baby-Doll."

"Euh! Euh! Baby-Doll."

"I love you!" she said, and kissed him.

Shane smiled at her. Then he was off, sprinting again. I started after him, but he surged ahead, dodging people on the sidewalk, and leaped across the street, ahead of the traffic. He got to Oliver before the light changed, the nimblest pedestrian in New York, leaving me on the wrong side of the street.