It is hard to make a positive case for the prospects of the Middle East these days. In Egypt and Libya, the Arab Spring has turned into winter, Yemen’s brief spring into something worse. Tunisia’s hold on its gains is fragile (with Libyan refugees adding to the strain). Syria seems in endless turmoil and its million refugees are undermining Jordan and Lebanon, which have their own problems. The Israel-Palestine conflict seems even less amenable to solution than for many years.

Autocratic regimes, corruption and human rights abuses prevail. The “youth bulge,” the high percentage of people under 25 (in seven of the 17 countries in the region it is over 50 per cent), seems to promise demographic havoc, continued high unemployment and alienation. The recent halving of oil prices could jeopardise the “stable” Gulf states and Saudi Arabia, where the recent death of its King, and the advanced age of his successor, has forced questions about future stability to the fore. And of course, terrorism, now seemingly entering a freelance phase that stymies intelligence efforts everywhere, begins to tip this view of the future into outright fear.

It is true that many parts of the region are in a bad state, and share some of these problems. In the past 20 years, two-thirds of the region’s countries in different ways have stalled in their development. Of the six world regions where the World Bank tracks poverty rates (which are on the decline worldwide), only south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have done worse than the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region in the last two decades. And while there has been economic growth in the oil rich countries of the Arabian Peninsula they too have failed to move at more than a snail’s pace towards social inclusion, let alone democracy. In contrast, outside the region, in Asia in particular, but also in parts of Latin America, there have been astonishing examples of transformative development—not just China or the movement from third to first world of the two biggest Asian Tigers (South Korea and Taiwan) but the rapid catching-up of Thailand, Indonesia, Chile and Brazil.

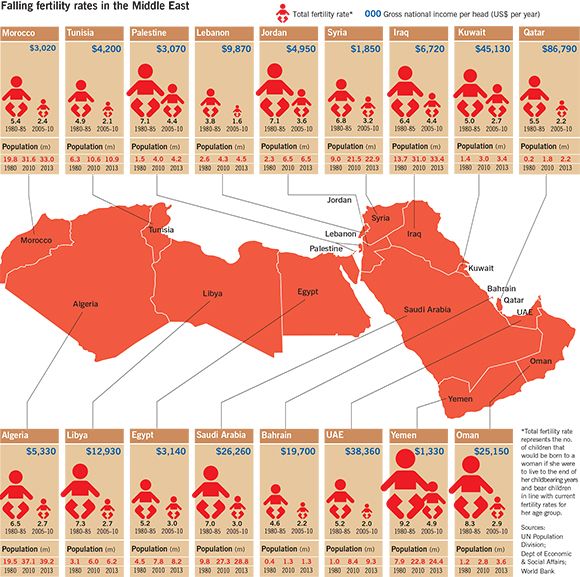

But all the same, in the MENA region there is dynamism alongside stiff-necked righteousness, there is confidence and pride layered in with the loss of self-esteem, humour alongside the anger. We should not write off the prospects for development. Civil society in some places has proved resilient, fertility rates and thus population growth are falling, and the diaspora now stretching around the world will have overwhelmingly positive effects. Easy generalisations about the region conceal huge differences—and within that, examples of success and great potential. The reasons for gloom are undeniable, but the reasons for eventual optimism are too easily dismissed.

The “Middle East” is still useful geographical shorthand, but the 17 nations of the MENA region are profoundly different from one another, as any travel through the region shows (I have lived in three of them, and travelled and worked in all but four of the rest). They differ in natural resources, political economy and even in their varieties of spoken Arabic, often mutually unintelligible, despite the official overlay of literary Arabic. Tastes, aesthetics and cuisine are more different in the MENA region than within much of sub-Saharan Africa. Moroccan cuisine and what can at best be described as “cooking” in Yemen have nothing in common. In Yemen the preferred illicit alcohol is whisky while in North Africa it is wine and beer.

In the early 1980s, when I lived in what was then North Yemen, the country had an in-your-face fierceness (seemingly every male older than 11 was armed), and a reverence for weapons visible in its stone architecture decorated with symbols of AK-47s and the traditional Yemeni jambiya knife. Sana’a, then with a population of no more than 100,000 (now about 2m), had a kind of nonchalant order, but no visible signs of civic pride. Dead dogs were left to desiccate in the high desert air; automobile parts sank into the sand beside the unpaved streets; and plastic bags, discarded everywhere, were lifted up by dust devils to decorate the thorn trees in pastel greens and pinks. Sana’a was an Arab Dodge City—albeit more than 2,000 years old—of rugged individuals where “social capital”—the connective tissue that gives rise to inter-group cooperation—resided, if anywhere, in family and tribal identity. Of course Sunni Islam (roughly two-thirds of the population) ran through everything, but it seemed a formal overlay. What counted was nisba, where you were from, to what entity you belonged, and the system of tribute that reinforced those ties.

Until the 1960s there was no “development” in Yemen. The country had at best a handful of doctors, few health facilities, and virtually no roads until the Chinese came to connect the Red Sea coast with the capital. Yemen’s royal rulers until the early 1960s tended to travel by horse-drawn carriage or on horseback; when the dissolute Imam Ahmad Bin Yahya (king from 1948 to 1962) first owned a car he could not go much further than the palace grounds. But in the early 1980s the prospects of development seemed good, if not bright; the idea that outsiders could help Yemen develop with health, water and agriculture projects, training and advice was widely shared.

A third of a century later, Yemen remains in key ways unchanged. Despite its discovery of oil in the late 1980s, close to half its population lives below the poverty line, food is scarce and supplies of water, which in the early 1980s began to be “mined” out of deep aquifers, are dwindling. The diaspora in the United Kingdom, as well as in Michigan and California, has grown; the American presence in Yemen has risen with its foreign aid, and North Yemen and South are now one country. But strife is now more violent and pronounced, more about Islam and power and less about the gang-like territorial feuds that characterised it before.

In contrast to Yemen’s recalcitrant chaos, Morocco, relatively calm, has made slow but steady progress. Sixteen years before I arrived in Yemen, I taught English at a Lycée in Fez. In 1964, Morocco had been independent for eight years; the main French language newspaper was called Le Petit Marocain—with no one questioning (or even noticing) the derogatory cast of the name; French was the language of the educated class and the Lycée was still run by French administrators. The country was relatively isolated. Royal Air Maroc could get you from the capital Rabat to Paris and not much beyond. Rabat itself had the feel of a small town and Marrakesh had one hotel capable of hosting the few European tourists.

Yet in contrast to Sana’a, Fez was a city with tremendous pride, an intellectual class and a self-conscious aesthetic. Its complex guild system enabled artisans from bookbinders to brass engravers to leather workers to pass on their craft, not for the benefit of the tourism industry (then in its infancy) but because their work was in demand by Moroccans. Marshal Hubert Lyautey, the first French administrator of Morocco (from 1912 to 1925), his paternalism aside, respected Fez’s integrity enough to build the Frenchified “ville nouvelle” a half mile away from the old city. For all its internal contrasts—its Berber tribes with their different language, its (then) hundreds of thousands of Jews, its centuries-long tensions between rebellious countryside and central authority—Morocco gave the impression of a distinctive place: a densely layered complex society that was pretty comfortable, as the French say, in its skin.

Today, with a population almost triple that of the mid 1960s, it is developing, if bumpily and with inequities. It has four-lane highways, international air travel, a high-speed rail system under construction, a liberal arts English-language university (Al-Akhawayn, which opened in 1995), preferential trade agreements with the European Union and the United States, important agricultural exports, a growing small parts and textile industry, and of course tourism. Eighty-four per cent of the population has access to safe drinking water; 75 per cent to improved sanitation facilities; female life expectancy is 80 years; and it had a Gross Domestic Product per head of $3,092 in 2013 (although at least 15 per cent of the population lives below the poverty line). In 2004, it saw the passage of the women-oriented family code, the Mudawana.

What explains the difference between the two? In Morocco’s case, some point to Sunni homogeneity, its three-century old monarchy and the general population’s reverence for its kings’ identity as descendants of the Prophet, as key forces for stability. It has benefited too, some analysts would have it, from its distance from Islam’s current and past political and religious centres (Mecca, Baghdad, Damascus). Controversially, some hold that its 44-year long semi-colonial existence under France left behind institutions critical for running the country today. Others reach further back, to its Berber heritage, and to the basic facts of its geography, at once protecting it from easy invasion, its mix of fertile soil and desert, of wet and dry.

Those explanations each have some value, but they show too how deeply present fortunes are derived from the past. Their complexity can be repeated across the region. Tunisia, for example, 700 miles to the east of Morocco along the same Mediterranean littoral, has a vastly different history. Perhaps its easy access to invaders like the Carthaginians and the Romans explains its relative cosmopolitanism and adaptability. Until recently, it was probably the most promising development story in the region, with call centres and a western-oriented educated class, and its seemingly much looser connections with orthodox Islam; under its liberator Habib Bourguiba, Tunisia was the only MENA country to allow factory workers to eat during Ramadan, to keep up production. Well into the early 2000s, Tunisia’s social development indicators topped those of the other North African countries not to mention the then 52 other countries on the African continent. In terms of equality, 46.4 per cent of income was in the hands of 60 per cent of the population; in life expectancy Tunisia was number two, behind the Seychelles; it was also number two in manufactured goods, and it had the lowest national poverty headcount as a percentage of population on the continent. Between 1982 and 2000, according to the World Bank, Tunisia had the highest percentage drop in the fertility rate of any country in Africa.

The central point is that the MENA countries have been developing in very different ways—the region boasts media-ready showcases of progress as well as paralysis. The Gulf states now display their stunning architecture, successful airlines and highways. Unimaginable 30 years ago, the UAE’s capital Abu Dhabi today hosts branches of the Louvre, the Guggenheim and New York University. And Saudi Arabia, Yemen’s northern neighbour, which until the discovery of oil always had fewer natural advantages, developed by outsourcing, using its new money.

All the same, conventional economic figures often fail to capture the ways these countries are not matching growth with social development. Looking at Gross National Income per head, 70 per cent of the MENA countries are in the World Bank’s ranks of upper-middle and high-income countries (examples are Algeria, Jordan, Tunisia, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia). But in terms of literacy, labour productivity, scientific and technological innovation, the status of women, political freedoms and human rights, most of them are laggards. We have here the apparent contradiction of “rich” yet “underdeveloped,” at least as we conventionally describe social development.

“Today… the spirit of science in the Muslim world is as dry as the desert"Many explanations have been put forward for the region’s struggles compared with much of the “developing world.” It is tempting to reach for monolithic explanations, as did Bernard Lewis in his widely read 2002 book What Went Wrong? He puts the emphasis on Islam, on the lack of separation of religion and state which may have confounded the development of institutions of the state, and on a persistent sense of historical humiliation. Some of that has some force. And yes, the position of women removes half the population from productive economic activity. The prevalence of the values around honour and shame may also be obstacles to change. Undeniably, a lack of freedom runs through many countries (Morocco’s human rights abuses continue under its new King despite his promise to do things very differently from his father, Hassan II). Demographics are a well analysed but immense hurdle to any attempt to raise living standards; about half of the population in the region is under 25, and it is hard for economic growth to keep ahead of the numbers of unemployed young people.

Some, too, point to a relative lack of achievement in science and technology. As Pakistani physicist Pervez Amirali Hoodbhoy lamented in a 2007 Physics Today article:

“Today… the spirit of science in the Muslim world is as dry as the desert. Muslim countries have nine scientists, engineers and technicians per thousand people, compared with a world average of 41.”

To the extent that the generalisations have value, it is because the MENA countries’ histories do share some important common themes with the rest of the developing world, particularly since the Second World War. Faced with the modern west, with its industrial, and post-war military power, the newly independent states in Africa and Asia in the 1950s and 1960s had two powerful motives according to anthropologist Clifford Geertz in his essay, Old Societies and New States. First was “the desire to be recognised as responsible agents whose wishes, acts, hopes, and opinions ‘matter’... a social assertion of the self as ‘being somebody in the world.’” And second, they shared a “demand for progress,” two motives that he suggests were a function of feeling left out.

In the Islamic world specifically, which had of course once been a world dominant civilisation, people were similarly “seeking a satisfactory definition of their place in the modern world,” as historian Marshall Hodgson put it in his monumental work The Venture of Islam. And the key reference point in that search for definition was the west. The western-oriented modernisers became “socialists” when they began to realise the limits of communism and of American domination. In their struggle against the left, Morocco and Tunisia supported Islamic groups in the 1960s and 1970s. Then socialism too stopped being a good thing, and with the rise of Israeli power came pan-Arabism, and a negative reaction to western technical aid as a form of “neo-colonialism.” And so, over almost a century, an effort to become like the west became a revolt against it.

Marginalisation and alienation, frustration and dissatisfaction, as trite as they may seem, remain powerful forces. A half century ago, with great prescience, economist and historian Robert L Heilbroner said “development is apt to be a time of awakening hostilities, of newly felt frustrations, of growing impatience and dissatisfaction.” And, as Geertz put it in that same year (1963), “the new states are abnormally susceptible to serious disaffection based on primordial attachments [to kinship, place, language, religion and social practices].” Since the beginning of the Arab Spring four years ago, what we have been seeing is precisely a public eruption of this disaffection and alienation. It is noteworthy that the word alienation in Arabic (ightirab) is based on the root for sunset (“the west”) and in modern literary Arabic dictionaries the word ightirab means both alienation and westernisation.

There is plenty of reason to worry about those forces continuing and the reactions to them. In Egypt, a six-decade long habit of military rule has reasserted itself. In other countries, conflicts buried for generations are now ascendant, as is the Sunni/Shia conflict in Iraq and to some extent in Lebanon, Syria and Yemen. Libya, which had made significant strides under Gaddafi, with child marriage outlawed, illiteracy practically wiped out and a skilled managerial class, after Gaddafi had the chance of opening to the world. Yet it is now falling into what is looking like a prolonged civil war about power, past grievances, tribal dominance and Islamism.

However, none of these accounts suggests that the prospect of development in the MENA area is doomed. Instead there is a strong case to be made that the countries of the region are likely eventually to follow the same trajectory of almost every other country so far: modernisation (that is, “westernisation”) eventually displaces and weakens alienation.

There are at least four reasons for optimism in the region. The first is that civil society, while weaker in the MENA region than the rest of the world, is emerging and in some places, such as Morocco and Tunisia, is proving resilient if not prominent (Morocco recently created a government ministry of “relations with civil society”). Exact data are hard to come by but estimates of between 150,000 and 175,000 civil society organisations of all types (politically based, socially based, university based) are reasonable for the region. There are today 236 think tanks in the MENA region, almost none of which existed two decades ago. The current international emphasis on the importance of the civil society, of its role in transparency, in bolstering governments’ accountability to its citizens, of ensuring press freedom is seeping into consciousness everywhere, including the MENA region. There are new and young leaders in the wings, and current heads of state, like King Abdullah of Jordan, squeezed as he is, who “get it.”

A second reason is demography. Fertility rates have fallen dramatically in the last 20 years—Egypt’s by 42 per cent, Libya’s by 63 per cent, and Yemen’s by 47 per cent. The youth bulge of today reflects a previous high fertility rate, but the recent drop in fertility rates means a fall in the number of young men in the foreseeable future and hence a lowering of the threat of jihadism.

A third reason is urbanisation. The percentage of people in the MENA region who live in urban areas as of 2012 reached just a shade less than that of Europe and central Asia. Urbanisation is a mixed blessing, of course. Cities are cauldrons of discontent and insalubrious living for the poorest people in them, but they are also incubators of change.

A fourth, perhaps the most important reason for optimism about the region’s future, is the unifying force of globalisation. The role of globalised commerce is an old story; what is new is the movement of people, money and information—aided by faster, cheaper transport, porous borders, the sense of mobility itself, and the interconnectivity provided by the internet and social media. Tastes in clothing, food, music, film, leisure activities and electronics are converging. English is becoming the universal language. Like it or not (sameness is rather boring) we are tending to lose our differences and broaden our identities. There are examples of fierce resistance to that trend, but these exceptions are likely to prove the rule.

Every single country in the MENA region now has a diaspora living elsewhere, albeit with different degrees of integration. The scale of this phenomenon alone—the permanent residence of people outside their home countries—is unprecedented. There are Yemenis not only in the UK and the US, but in Italy and central Asia. There are 240,000 Egyptians in the US, most of them high-income earners, and they have formed over 40 civil society organisations focused on their identity as Egyptian-Americans. Educated Libyans, Moroccans, Tunisians, Iraqis, Lebanese, Syrians, Jordanians live, work and are citizens of countries from Australia to Canada, from western Europe to the US. For the most part they do not give up their ties and as they see change happening in their origin countries, they see possibilities both for investment and influence. This awakening of the MENA region’s diasporas is becoming a force for change. Enlarge these diasporas to include labour migration and then we come to the flow of remittances, another force that carries change. Every single MENA country either imports or exports labour; the resultant money flows are significant (remittances worldwide dwarf foreign aid by at least a factor of between three and four.) In the MENA region, official statistics show at least $45bn in inflows. In Yemen, Jordan and Egypt they account for roughly 10 per cent of GDP. The actual figures are likely higher.

Labour migration is often about necessity not choice, as much refugee movement is about desperation. But that movement, for whatever reason, prompts a constant flow of new ideas and attitudes. An orientation to a different and more shared future is inevitable. It will not be utopia—individual self-interest, imitation, envy, ambition, acquisitive instincts will grow. But isolation, a retreat to an imagined past of rigid order is unlikely to be a sustainable option.

The last half century suggests that issues of identity become weaker as modernisation and globalisation get stronger. Today, Europe looks at its centuries of conflict as almost quaint. And while there are hundreds of conflicts still alive around the world, most tend to move towards resolution—some by separation, others by re-unification. The long Tamil/Sinhalese conflict in Sri Lanka is behind us, as is that between Igbos and Hausa in Nigeria, the Chinese and the Malays in Malaysia, the Berbers and Arabs in Morocco, the Moros in the Philippines. In the cases of Timor-Leste, Eritrea, Bangladesh, South Sudan, separatism has prevailed. The situation of the Kurds in Syria, Iraq and Turkey, of Tibetans and Uighurs in China, current strains in Myanmar remain unresolved, as do, to put it mildly, the situations in Israel-Palestine, Cyprus and now Syria. It is a good bet to ask not if they will resolve, or if all these countries will develop, but when and how?

It is just about conceivable that Yemen will look the same in 2050 or even 2100 as it does today—but it is unlikely. The longer we wait, the more likely that Yemen, and the other countries of the region, will resemble their neighbours, both near and far. Indeed, the countries in the region will inevitably become more and more part of the larger world, and we do them and ourselves a disservice if out of fear or other inchoate sentiments, we see their current differentness as an obstacle to progress.