Read Prospect's interview with Housing Minister Brandon Lewis

In my experience of public policy and government, big challenges do not always require complex solutions. Often the essential reforms are simple. I am also wary of the gibe: “If it were simple, it would have been done already.” This confuses “simple” with “easy”. If simple reforms are controversial and difficult to implement—because they radically challenge the status quo—then politicians tend to default into waffle, half measures or complex tweaks of the status quo, achieving little. This inaction, or avoiding action, can last decades.

The creation of academies, the Teach First training programme and the proposed High Speed Rail Two were all simple reforms or projects to address fundamental problems of (respectively) school standards and transport capacity. Yet at their inception they were very controversial and difficult.

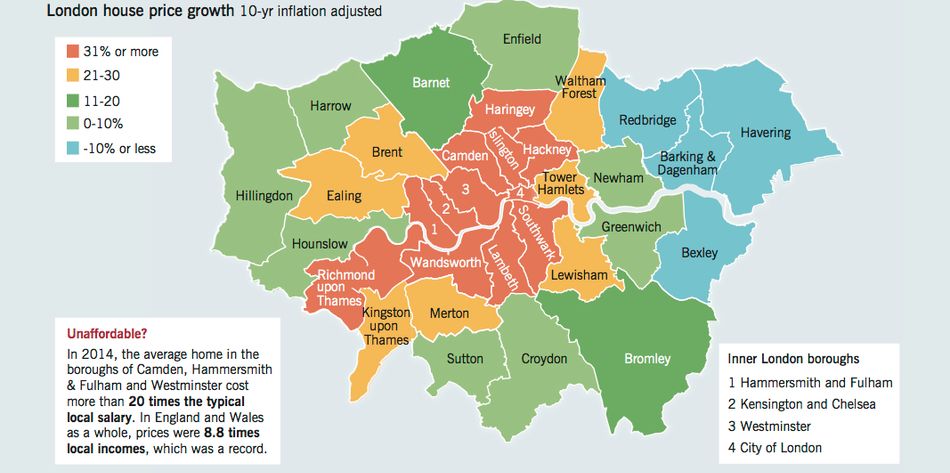

These precepts seem to me to apply to today’s housing crisis, which is concentrated in London and the southeast, across much of which prices and rents are now sky high. The problem of grossly inadequate housing supply in southern England is multifaceted. The cast of culprits includes the planning system, the Green Belt, land banking by private developers, financial controls on local authorities, low numbers of houses built relative to available land (low “density” in the jargon), the operation of the “right to buy” scheme which allows council tenants to buy their council homes at a discount, foreign buyers treating London property as gold bars, the absence of a private rented sector managed by institutional investors, and more besides. Each of these issues has spawned micro-reform agendas, many of them highly complex. However, stand back, and two truths appear to me to get to the heart of the problem of housing supply, each of which needs to be addressed by simple—if difficult—reforms.

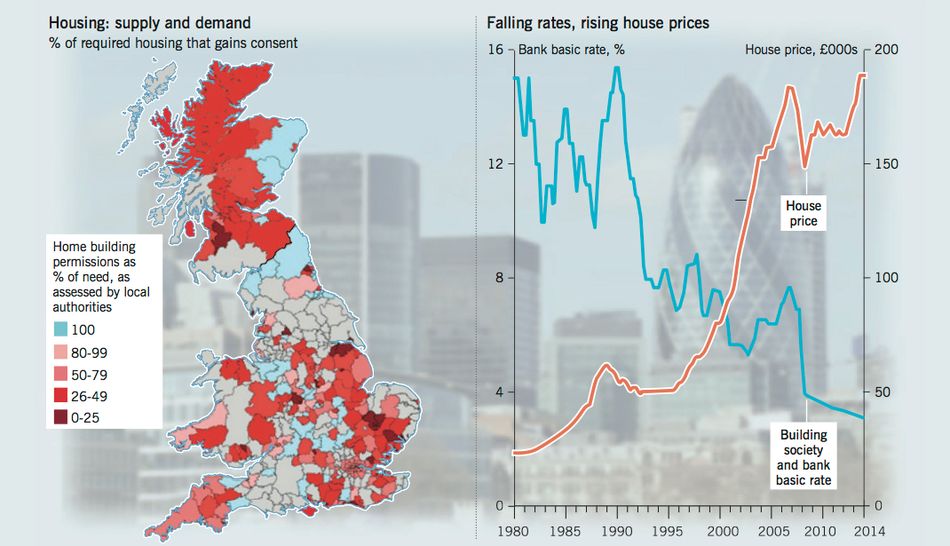

First, the collapse in housebuilding has largely been a function of the withdrawal of the state and local authorities from planning and developing new settlements since the mid-1970s, including new towns. Housebuilding has been almost entirely left to the private and voluntary sectors which cannot meet demand alone.

Second, land is the main requirement—and cost—of housing and, given modern employment and living patterns, suitable urban land should be the key priority for development, particularly land with good transport links within and near London. Most of this land turns out to be in the hands not of the private sector but the public sector; yet most public authorities are doing little to mobilise the bulk of their suitable public land for homebuilding.

There is a vital national dimension to this, as well as a local one. In the immediate postwar decades, central government not only funded and encouraged local authorities to become developers, it was also a significant developer in its own right, through new towns and major urban extensions. From Stevenage in 1946 to Milton Keynes in 1967, the state developed nearly 30 new towns and major urban extensions, mostly in southern England. The new towns around London now have a population of some 1.5m; Milton Keynes alone has a population of 260,000.

As for land, for all the controversy about private sector landbanking, by far the biggest owner of undeveloped or under-developed land in England’s cities, notably London, is the public sector. There is no register of public land in cities, and most individual public authorities (including local authorities) do not publish or even map their landholdings, which is partly why their extent is unrecognised. For example, the scale of just two public authorities in London —local councils and Transport for London—is vast.

London’s local councils typically own between a quarter and a third of the land within their boroughs. In Southwark, occupying a swathe of the central-south bank of the Thames, the figure is an estimated 43 per cent. Much of this borough owned land is piecemeal holdings; much is within the boundaries of the capital’s estimated 3,500 large council housing estates. Islington council alone owns about 150 large council estates (that is, 50 homes or more), situated on some of the most expensive land in the world.

Much of this land is undeveloped or underdeveloped, and housing densities are typically low. Southwark council, for example, owns an estimated 10,000 garages, mostly on council estates —dating back to the 1960s and 70s, when lock-up garages were the thing, including in the inner city. Why are they still there? It relates directly to the first point about an inactive modern state. Local councils largely stopped planning and building housing estates 35 years ago, including the infilling and redevelopment of their existing estates. Just keeping these estates to a decent standard of repair and amenity has been their preoccupation, and many fail even that test. Central government mandated this diminished role for local authorities, alongside its own withdrawal from planning and building major new settlements (Canary Wharf being a significant exception).

Recent mapping shows Transport for London (TfL), which operates the capital’s underground and bus services, to be an even larger landowner than any of the boroughs. TfL believes it owns 5,800 acres, an area larger than the entire London Borough of Camden (Hyde Park is 350 acres). Much of this is operational land, but again much of it is lightly developed or undeveloped. It includes 61 car parks and 270 stations. Most of these sites, including central London stations in prime locations, have gone largely undeveloped since they were built or acquired a century ago. TfL has just five officials responsible for estate development, a fraction of the number dealing with media relations.

TfL’s land and stations are predominantly north of the Thames. Network Rail, which owns the national rail infrastructure, has similarly large landholdings in the capital (although it publishes no figures), including some 370 stations, concentrated in south London. The National Health Service, the Ministry of Defence and a plethora of other government departments and agencies also have large landholdings in the capital, much of it surplus or lightly developed.

Poor management of public assets, notably public land, is a global issue. The architect Richard Rogers has spent decades highlighting the development potential of “brownfield” land within major cities. A recent book by Swedish public sector reformers Dag Detter and Stefan Fölster, The Public Wealth of Nations: How Management of Public Assets Can Boost or Bust Economic Growth, charts the extraordinary scale of public assets accumulated over decades and centuries. “The largest pool of wealth in the world is comprised of commercial assets that are held in public ownership,” they write. “The global total [of these assets] is twice the world’s total pension savings and ten times the total of all the sovereign wealth funds on the planet. If professionally managed it could generate an annual yield of $2.7 trillion, more than current global spending on infrastructure.”

There are, however, notable exceptions, including small but dynamic nations and city states (or quasi-city states) acutely short of land, including the Netherlands, Singapore and Hong Kong. For example, the Hong Kong public transport operator, MTR, is one of the city’s major housing and property developers. Over the last four decades it has been allocated state land on transport corridors at pre-development value, on condition that it develops the land for housing and commerce, using the proceeds to fund the building of new metro lines which generate much of the enhanced value. This has led to intensive development around stations, most recently at West Kowloon. MTR has built more than 90,000 homes and now earns as much income from housing and property as from its transport operations. It has a staff of hundreds in its planning and property divisions.

As for the Netherlands, in his final book published last year, Good Cities: Better Lives, the late urban planner Peter Hall hailed the Dutch Vinex programme, through which central government achieved agreements with local authorities that generated 455,000 homes between 1996 and 2005. This followed the 1991 Vinex report, a national spatial strategy which set out a plan for new towns and urban extensions, much as the Abercrombie Plan did for postwar London in 1944. The guiding objective of Vinex, Hall noted, was that “The houses had to be in the right places, close to existing cities... above all in the heart of the Randstad (the core Dutch city-region incorporating Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht and The Hague), and also to minimise travel to cities and secure maximum use of public transport, walking and bicycles.”

So, the withdrawal of the state and local authorities from planning new settlements, on a local and national basis, and the poor use of public land, particularly in and around London, are critical factors constraining the supply of new housing at scale where it is urgently needed. There appear to me to be three simple—if difficult—reforms to address these two problems.

First, local authorities in areas of housing shortage should be required by the state once again to become developers and place makers. Partly this will be about planning for far more housing and amenities on brownfield land where there is strong demand (particularly in London); partly it will be about new and expanded settlements, where environmental considerations need to be weighed with a view to action rather than inaction. Local authorities, including the Greater London Authority, need a new generation of public master planners and developers for this purpose, focused on sustainable development and social need, not just development control. They also need financial freedom to invest in housing on their own account.

Second, the state—central government—once again needs to take a lead by systematically planning new transport infrastructure to support new housing, and by becoming a planner of major new settlements in its own right. I am persuaded that the best course is to develop “garden city” extensions to successful existing towns and cities in areas of high housing and employment demand, rather than developing entirely new towns like Milton Keynes, on the model advocated by David Rudlin, the urban designer who last year won the Wolfson prize for his work on tackling England’s housing shortage. Rudlin proposed doubling the size of 40 towns and cities with good existing infrastructure and public transport connections which could be further enhanced, including Oxford, Guildford, Norwich, Reading and Stratford-upon-Avon.

The regeneration of existing council estates is a vitally important element; it is probably also the most difficult. Within London, only a tiny fraction of the capital’s estimated 3,500 estates have been substantially redeveloped in the last decade (50 according to a recent report by the London Assembly), and the assembly has identified only about 100 schemes currently underway. However, each of these estates is home to hundreds or thousands of families, and gaining their participation and consent to change is essential. This requires a big improvement in the quality of the housing and local amenities to create new “city villages,” not simply infilling and an increase in densities.

The creation of new city villages emphatically does not mean a return to overcrowding. Density and desirability are not contradictory, in the context of London’s existing low densities. Inner London’s population is still 1.7m below its 1939 peak. The expensive terraces of Kensington and Holland Park boast among the highest residential densities in London, thanks to 19th-century estate planning.

Hackney council, under Mayor Jules Pipe, is a leader and a model. The council is engaged in 18 major estate redevelopment schemes, far more than any other of London’s 33 boroughs, taken forward by a large team of master planners and regeneration experts. A key partners is L&Q, one of England’s largest housing association, which is in the process of doubling in size with 50,000 new homes planned or in the pipeline. Yet this is being achieved with no state subsidy, nor even any requirement for gap funding or bridging loans. Cross-subsidy from new property for sale to the general market is more than paying for the entirety of its estate redevelopment projects, including the provision of more social homes, and L&Q’s strong balance sheet and credit rating are sufficient for it to borrow to finance the cost of investment. L&Q alone is confident that it could take on dozens of new projects, if it had willing local authority partners with suitable estate redevelopment projects.

Hackney council’s redevelopment of the Woodberry Down estate is a testament to social transformation. The former estate’s grim tenement blocks provided part of the film set for the Warsaw ghetto in Schindler’s List. It is now being demolished and rebuilt as a mid-rise, mixed-tenure community at nearly three times the previous density (5,550 new homes replacing the 1,981 former council flats). As well as the demolition of the estate and its replacement with entirely new and better housing, there is or will be three new public parks, shops, business premises, a new children’s centre, an expanded primary school and a new secondary school academy—an entire new village. Of the first 862 homes completed, 421 are for social rent, 135 for shared ownership and 306 for sale: a mixed community and a true social transformation.

The redevelopment of the huge Thamesmead estate on the River Thames east of Greenwich, by the Peabody Trust in partnership with local councils, is an equally bold initiative. The eastern Crossrail terminus at Abbey Wood, due to open in 2018, will serve the estate and transform its development potential. The vast, bleak 1960s concrete Thamesmead estate formed the backdrop for Stanley Kubrick’s chilling film A Clockwork Orange; it has changed all too little since the film was made in the early 1970s. Peabody plans an extra 10,000 homes on 100 acres of developable land, alongside regeneration of the existing housing stock and the enhancement of the large green spaces, waterways and lakes within Thamesmead.

Islington is also a model with the redevelopment of the Packington estate, a formerly notorious council estate between the Regent’s Canal and the Essex Road. With the buildings facing imminent structural collapse and riddled with asbestos, Islington council transferred ownership of the estate seven years ago to the Hyde Group housing association, for them to undertake redevelopment including new homes for sale to pay for most of the redevelopment. The new development comprises 791 homes, an increase of a third on the previous estate. Of these, 463 are for social rent, 300 for outright sale and 28 for shared ownership. This is creating a strong, balanced “village,” reinforced by the design which restores streetscapes and opens the development to its affluent neighbourhood. All social renters who wished to be housed in the new development have been as of right. Extensive engagement with the tenants and the 40 beneficiaries of the right-to-buy scheme helped shape the redevelopment and build community support. Partly as a result, the development includes 135 homes of between three and six bedrooms—all for social rent—as well as 650 one- and two-bedroom homes.

It is bold state action—central and local government leading development in partnership with the private and voluntary sectors, not abdicating its responsibilities to them—which will resolve the housing crisis. With its vast ownership of land, and its powers to plan, develop and finance, government can get the job done, and it has no one else to blame for inaction. It’s simple, really.

In my experience of public policy and government, big challenges do not always require complex solutions. Often the essential reforms are simple. I am also wary of the gibe: “If it were simple, it would have been done already.” This confuses “simple” with “easy”. If simple reforms are controversial and difficult to implement—because they radically challenge the status quo—then politicians tend to default into waffle, half measures or complex tweaks of the status quo, achieving little. This inaction, or avoiding action, can last decades.

The creation of academies, the Teach First training programme and the proposed High Speed Rail Two were all simple reforms or projects to address fundamental problems of (respectively) school standards and transport capacity. Yet at their inception they were very controversial and difficult.

These precepts seem to me to apply to today’s housing crisis, which is concentrated in London and the southeast, across much of which prices and rents are now sky high. The problem of grossly inadequate housing supply in southern England is multifaceted. The cast of culprits includes the planning system, the Green Belt, land banking by private developers, financial controls on local authorities, low numbers of houses built relative to available land (low “density” in the jargon), the operation of the “right to buy” scheme which allows council tenants to buy their council homes at a discount, foreign buyers treating London property as gold bars, the absence of a private rented sector managed by institutional investors, and more besides. Each of these issues has spawned micro-reform agendas, many of them highly complex. However, stand back, and two truths appear to me to get to the heart of the problem of housing supply, each of which needs to be addressed by simple—if difficult—reforms.

First, the collapse in housebuilding has largely been a function of the withdrawal of the state and local authorities from planning and developing new settlements since the mid-1970s, including new towns. Housebuilding has been almost entirely left to the private and voluntary sectors which cannot meet demand alone.

Second, land is the main requirement—and cost—of housing and, given modern employment and living patterns, suitable urban land should be the key priority for development, particularly land with good transport links within and near London. Most of this land turns out to be in the hands not of the private sector but the public sector; yet most public authorities are doing little to mobilise the bulk of their suitable public land for homebuilding.

"By far the biggest owner of undeveloped or under-developed land in England’s cities, notably London, is the public sector"The scale of the housebuilding shortfall is stark. More than 200,000 new homes a year are required to keep pace with household formation, at least 40,000 of them in London. Last year, there were only 119,000 completions, 18,000 in London. Between 1950 and 1980, when annual home completion rates were consistently above 200,000, this included substantial planning and building by local authorities and central government. Local authorities accounted for half of all new home completions between 1960 and 1980. Last year, just 1,180 new homes were built by local authorities, one per cent of the total. Housing associations, doing excellent work in many communities, are only partially filling this gap, building only 24,000 homes last year.

There is a vital national dimension to this, as well as a local one. In the immediate postwar decades, central government not only funded and encouraged local authorities to become developers, it was also a significant developer in its own right, through new towns and major urban extensions. From Stevenage in 1946 to Milton Keynes in 1967, the state developed nearly 30 new towns and major urban extensions, mostly in southern England. The new towns around London now have a population of some 1.5m; Milton Keynes alone has a population of 260,000.

As for land, for all the controversy about private sector landbanking, by far the biggest owner of undeveloped or under-developed land in England’s cities, notably London, is the public sector. There is no register of public land in cities, and most individual public authorities (including local authorities) do not publish or even map their landholdings, which is partly why their extent is unrecognised. For example, the scale of just two public authorities in London —local councils and Transport for London—is vast.

London’s local councils typically own between a quarter and a third of the land within their boroughs. In Southwark, occupying a swathe of the central-south bank of the Thames, the figure is an estimated 43 per cent. Much of this borough owned land is piecemeal holdings; much is within the boundaries of the capital’s estimated 3,500 large council housing estates. Islington council alone owns about 150 large council estates (that is, 50 homes or more), situated on some of the most expensive land in the world.

Much of this land is undeveloped or underdeveloped, and housing densities are typically low. Southwark council, for example, owns an estimated 10,000 garages, mostly on council estates —dating back to the 1960s and 70s, when lock-up garages were the thing, including in the inner city. Why are they still there? It relates directly to the first point about an inactive modern state. Local councils largely stopped planning and building housing estates 35 years ago, including the infilling and redevelopment of their existing estates. Just keeping these estates to a decent standard of repair and amenity has been their preoccupation, and many fail even that test. Central government mandated this diminished role for local authorities, alongside its own withdrawal from planning and building major new settlements (Canary Wharf being a significant exception).

Recent mapping shows Transport for London (TfL), which operates the capital’s underground and bus services, to be an even larger landowner than any of the boroughs. TfL believes it owns 5,800 acres, an area larger than the entire London Borough of Camden (Hyde Park is 350 acres). Much of this is operational land, but again much of it is lightly developed or undeveloped. It includes 61 car parks and 270 stations. Most of these sites, including central London stations in prime locations, have gone largely undeveloped since they were built or acquired a century ago. TfL has just five officials responsible for estate development, a fraction of the number dealing with media relations.

TfL’s land and stations are predominantly north of the Thames. Network Rail, which owns the national rail infrastructure, has similarly large landholdings in the capital (although it publishes no figures), including some 370 stations, concentrated in south London. The National Health Service, the Ministry of Defence and a plethora of other government departments and agencies also have large landholdings in the capital, much of it surplus or lightly developed.

Poor management of public assets, notably public land, is a global issue. The architect Richard Rogers has spent decades highlighting the development potential of “brownfield” land within major cities. A recent book by Swedish public sector reformers Dag Detter and Stefan Fölster, The Public Wealth of Nations: How Management of Public Assets Can Boost or Bust Economic Growth, charts the extraordinary scale of public assets accumulated over decades and centuries. “The largest pool of wealth in the world is comprised of commercial assets that are held in public ownership,” they write. “The global total [of these assets] is twice the world’s total pension savings and ten times the total of all the sovereign wealth funds on the planet. If professionally managed it could generate an annual yield of $2.7 trillion, more than current global spending on infrastructure.”

There are, however, notable exceptions, including small but dynamic nations and city states (or quasi-city states) acutely short of land, including the Netherlands, Singapore and Hong Kong. For example, the Hong Kong public transport operator, MTR, is one of the city’s major housing and property developers. Over the last four decades it has been allocated state land on transport corridors at pre-development value, on condition that it develops the land for housing and commerce, using the proceeds to fund the building of new metro lines which generate much of the enhanced value. This has led to intensive development around stations, most recently at West Kowloon. MTR has built more than 90,000 homes and now earns as much income from housing and property as from its transport operations. It has a staff of hundreds in its planning and property divisions.

As for the Netherlands, in his final book published last year, Good Cities: Better Lives, the late urban planner Peter Hall hailed the Dutch Vinex programme, through which central government achieved agreements with local authorities that generated 455,000 homes between 1996 and 2005. This followed the 1991 Vinex report, a national spatial strategy which set out a plan for new towns and urban extensions, much as the Abercrombie Plan did for postwar London in 1944. The guiding objective of Vinex, Hall noted, was that “The houses had to be in the right places, close to existing cities... above all in the heart of the Randstad (the core Dutch city-region incorporating Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Utrecht and The Hague), and also to minimise travel to cities and secure maximum use of public transport, walking and bicycles.”

So, the withdrawal of the state and local authorities from planning new settlements, on a local and national basis, and the poor use of public land, particularly in and around London, are critical factors constraining the supply of new housing at scale where it is urgently needed. There appear to me to be three simple—if difficult—reforms to address these two problems.

First, local authorities in areas of housing shortage should be required by the state once again to become developers and place makers. Partly this will be about planning for far more housing and amenities on brownfield land where there is strong demand (particularly in London); partly it will be about new and expanded settlements, where environmental considerations need to be weighed with a view to action rather than inaction. Local authorities, including the Greater London Authority, need a new generation of public master planners and developers for this purpose, focused on sustainable development and social need, not just development control. They also need financial freedom to invest in housing on their own account.

Second, the state—central government—once again needs to take a lead by systematically planning new transport infrastructure to support new housing, and by becoming a planner of major new settlements in its own right. I am persuaded that the best course is to develop “garden city” extensions to successful existing towns and cities in areas of high housing and employment demand, rather than developing entirely new towns like Milton Keynes, on the model advocated by David Rudlin, the urban designer who last year won the Wolfson prize for his work on tackling England’s housing shortage. Rudlin proposed doubling the size of 40 towns and cities with good existing infrastructure and public transport connections which could be further enhanced, including Oxford, Guildford, Norwich, Reading and Stratford-upon-Avon.

"The regeneration of existing council estates is a vitally important element; it is probably also the most difficult"The third reform is to make housing development—particularly social and affordable housing—a key requirement for all public authorities with suitable public land, enforced by local authorities (and in London also by the Mayor) with powers to take over the planning and development of public land directly where this is not happening. Transport for London, Network Rail, the NHS, the armed forces and other state agencies with major landholdings would be covered. For local authorities in areas of high housing demand, there should also be a requirement to develop their own land to provide more housing.

The regeneration of existing council estates is a vitally important element; it is probably also the most difficult. Within London, only a tiny fraction of the capital’s estimated 3,500 estates have been substantially redeveloped in the last decade (50 according to a recent report by the London Assembly), and the assembly has identified only about 100 schemes currently underway. However, each of these estates is home to hundreds or thousands of families, and gaining their participation and consent to change is essential. This requires a big improvement in the quality of the housing and local amenities to create new “city villages,” not simply infilling and an increase in densities.

The creation of new city villages emphatically does not mean a return to overcrowding. Density and desirability are not contradictory, in the context of London’s existing low densities. Inner London’s population is still 1.7m below its 1939 peak. The expensive terraces of Kensington and Holland Park boast among the highest residential densities in London, thanks to 19th-century estate planning.

Hackney council, under Mayor Jules Pipe, is a leader and a model. The council is engaged in 18 major estate redevelopment schemes, far more than any other of London’s 33 boroughs, taken forward by a large team of master planners and regeneration experts. A key partners is L&Q, one of England’s largest housing association, which is in the process of doubling in size with 50,000 new homes planned or in the pipeline. Yet this is being achieved with no state subsidy, nor even any requirement for gap funding or bridging loans. Cross-subsidy from new property for sale to the general market is more than paying for the entirety of its estate redevelopment projects, including the provision of more social homes, and L&Q’s strong balance sheet and credit rating are sufficient for it to borrow to finance the cost of investment. L&Q alone is confident that it could take on dozens of new projects, if it had willing local authority partners with suitable estate redevelopment projects.

Hackney council’s redevelopment of the Woodberry Down estate is a testament to social transformation. The former estate’s grim tenement blocks provided part of the film set for the Warsaw ghetto in Schindler’s List. It is now being demolished and rebuilt as a mid-rise, mixed-tenure community at nearly three times the previous density (5,550 new homes replacing the 1,981 former council flats). As well as the demolition of the estate and its replacement with entirely new and better housing, there is or will be three new public parks, shops, business premises, a new children’s centre, an expanded primary school and a new secondary school academy—an entire new village. Of the first 862 homes completed, 421 are for social rent, 135 for shared ownership and 306 for sale: a mixed community and a true social transformation.

The redevelopment of the huge Thamesmead estate on the River Thames east of Greenwich, by the Peabody Trust in partnership with local councils, is an equally bold initiative. The eastern Crossrail terminus at Abbey Wood, due to open in 2018, will serve the estate and transform its development potential. The vast, bleak 1960s concrete Thamesmead estate formed the backdrop for Stanley Kubrick’s chilling film A Clockwork Orange; it has changed all too little since the film was made in the early 1970s. Peabody plans an extra 10,000 homes on 100 acres of developable land, alongside regeneration of the existing housing stock and the enhancement of the large green spaces, waterways and lakes within Thamesmead.

Islington is also a model with the redevelopment of the Packington estate, a formerly notorious council estate between the Regent’s Canal and the Essex Road. With the buildings facing imminent structural collapse and riddled with asbestos, Islington council transferred ownership of the estate seven years ago to the Hyde Group housing association, for them to undertake redevelopment including new homes for sale to pay for most of the redevelopment. The new development comprises 791 homes, an increase of a third on the previous estate. Of these, 463 are for social rent, 300 for outright sale and 28 for shared ownership. This is creating a strong, balanced “village,” reinforced by the design which restores streetscapes and opens the development to its affluent neighbourhood. All social renters who wished to be housed in the new development have been as of right. Extensive engagement with the tenants and the 40 beneficiaries of the right-to-buy scheme helped shape the redevelopment and build community support. Partly as a result, the development includes 135 homes of between three and six bedrooms—all for social rent—as well as 650 one- and two-bedroom homes.

It is bold state action—central and local government leading development in partnership with the private and voluntary sectors, not abdicating its responsibilities to them—which will resolve the housing crisis. With its vast ownership of land, and its powers to plan, develop and finance, government can get the job done, and it has no one else to blame for inaction. It’s simple, really.