There are many pressing issues related to housing, health, education and our new relationship with the European Union that will dominate the policy debates until 8th June. Political parties will aim to win over voters quickly with messages on these emotive subjects. But amidst the urgency there is a genuine risk that we lose sight of the most pressing structural questions facing the UK economy—questions concerning labour productivity and living standards.

We at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research are highlighting this issue as part of our effort—with the Nuffield Foundation—to ensure that public debate in the run-up to the vote is informed by independent and rigorous evidence.

The UK has a poor record on labour productivity—particularly since the start of the financial crisis. It is not alone; most advanced economies suffered a sudden and sharp drop in labour productivity during the crisis period, but have yet to see much, if any, bounce back. What is striking about the UK performance is that we started with a large productivity deficit against our competitors before the crisis and that gap has got wider since then.

To put this in perspective, the latest official data for 2015—the most recent data we have on this subject—shows that G7 workers were on average producing some 15 per cent more output than UK workers. Another way to assess our productivity performance is by comparing productivity today with a pre-crisis average trend. Had UK productivity performance from 2008 to 2015 matched its pre-downturn trend, labour productivity would have been much higher in 2015: the figure is in excess of 15 per cent. The UK is the worst performer of any G7 economy on this metric. The poor productivity performance of the past decade has been a puzzle for economists and is yet to be fully understood.

Why does this matter and what can be done about it?

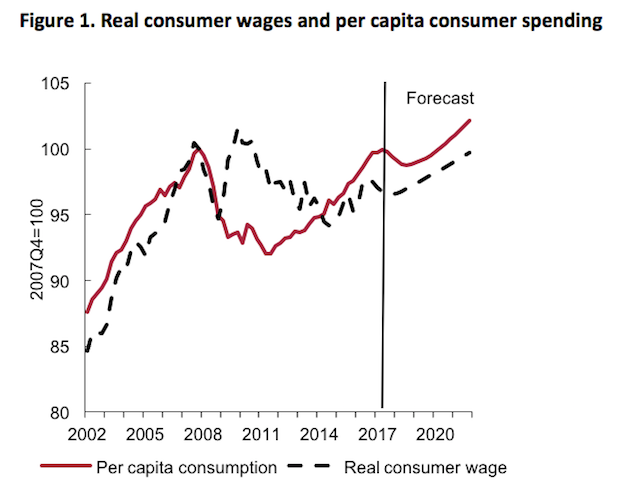

The simple answer is that labour productivity and wages tend to move together. Historical data shows that periods of high productivity tend to be accompanied by higher wage growth and lower productivity with lower wage growth. This time is no different.

Wage growth has slowed dramatically since the start of the crisis and remains at relatively low levels in spite of the fact that that the number of people employed in the economy is at record levels and the unemployment rate, at 4.7 per cent today, is below the level it was at the start of the financial crisis. Wage growth has averaged just 1.6 per cent since 2010, well below consumer price inflation which has averaged 2.2 per cent over the same period. This compares with an average growth rate of wages of around 5.2 per cent in the decade prior to the financial crisis. Wage growth has slowed to the point where the spending power of these wages has been squeezed significantly by inflation.

Consequently, as NIESR’s latest quarterly forecast, published today, reveals, consumer spending per capita is only expected to reach its pre-crisis peak in 2020, some 12 years after the start of the financial crisis (see figure 1). This is a shockingly poor record relative to historical standards.

Understanding the causes of weak productivity growth is crucial for income growth and for formulating a policy response during an election campaign. To be clear, we do not have a complete explanation for the collapse in productivity, but we must respond to what we already know. Further research in this field is badly needed as it is impossible to generate sustainable economic growth and deliver rising living standards without productivity growth.

One striking feature of the UK’s economic landscape is the low level of investment and, in particular, R&D spending compared with our major competitors. The UK has persistently spent less as a percentage of its GDP on R&D than Germany, the USA, Japan and France. It is unsurprising, then, that the UK has a negative productivity gap with each of these economies. That gap opened up in the 1980s. Among the major economies, only Italy spends materially less on R&D than the UK. Addressing this gap, through tax incentives, raising education levels, continuous on-the-job training and so on can have a long term beneficial impact on labour productivity.

If these measures are not pursued and should our trade relationship with the EU suffer after Brexit, there is the distinct possibility that UK productivity collapses further: to Italian levels.

Where will Theresa May’s surprise ballot leave the government, the opposition and a divided country? Join us for our big election debate on the 6th of June 2017. Tom Clark, Prospect’s editor, will be joined by Nick Cohen, Matthew Parris and Meg Russell of the Constitution Unit.