In the 60 years since Princess Elizabeth acceded to the throne, Britain has become a better place to live. More people think that than think the opposite (see YouGov’s extensive survey for Prospect, p38); those under 40, and in London and the south, are markedly more cheerful. Those who demur might read, in Simon Jenkins’s panorama (p30), his reminder of past attitudes to women, children and gay rights and to actions now defined as crime. It is easy to forget how much has changed.

True, Britain has lost most of the rest of its empire in that time; its military has shrunk; its population soared, and its countryside become more cluttered. Those have provoked a real sense of loss. As Peter Kellner puts it (p38), the polls paint a picture of a country that is “nervous, and small ‘c’ conservative.” Many cite immigration as its worst feature, the most startling result of the survey. But pride in a tradition of liberty and a culture of tolerance and openness to the world is also loud (p40).

Is that a contradiction? Yes, of a peculiarly British kind. In the national identity, there has long been a tussle between apparently incompatible strands. The worldly individualism that has led to the pre-eminence of the City has always vied with the belief in community that underpins the National Health Service. The independence that (rightly) kept Britain out of the euro has fought with a desire to shape decisions in Brussels and Washington. The creativity and innovation of which many are proud coexists with an inability to devise an education system or a second chamber of parliament appropriate to the modern world.

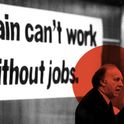

At its worst, that national ability to walk both sides of the line produces paralysis, mediocrity and an insidious disdain for change. At its best, it represents resilience and a rebuff to extremism. It is striking that each political party could read in these poll results support for its own most passionate themes. But it is the particular tragedy of the Lib Dems that although they stand for the freedoms which so many cite as the country’s finest quality, they have failed to turn that into a strong political voice. They could still do so. In the necessary reviews of the role of the City and media now underway, it would be regrettable if ministers, in pursuit of tighter regulation, set aside those values at the heart of British life.

Voicing those principles may now be Britain’s most valuable contribution abroad. Europe faces in acute form the growing problem of western democracies: how to hold on to their values during radical economic change. Oliver Kamm and Victor Sebestyen (p18 and p19) warn of the EU’s weakness in defending its own values; as Victor puts it, if it remains silent in the face of the latest assault on political freedoms in Hungary, it is hard to see what it is for. That is a point which William Hague, as foreign secretary, should make. The Diamond Jubilee celebrates not just the longevity of a monarch but the endurance of values central to British identity, which are absent or under threat in much of the world.

Britain’s brand of freedom

May 25, 2012