The post-Brexit blues:

The only dispute is how much money’s gone missing

After the Brexit vote, the pound tumbled and markets got jittery for a time, but there was no general slump. Brexit however—whatever it may turn out to mean—hasn’t happened yet. And both sets of forecasters retained on the public payroll are agreed the UK economy will, more likely than not, soon be smaller than it would have been if things had gone the other way. The Office for Budget Responsibility, the official watchdog on which Chancellor Philip Hammond relies when he’s setting tax and spending policies has revised down its forecast for growth through to the end of 2017 by 1.1 per cent, rising to 1.4 per cent by 2021. Some Brexiteers have rubbished that, arguing that this is a small number clouded in uncertainty. That is true, but uncertainty cuts both ways. The Bank of England, like many other commentators, has pencilled in an even sharper downgrade.

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Bank of England

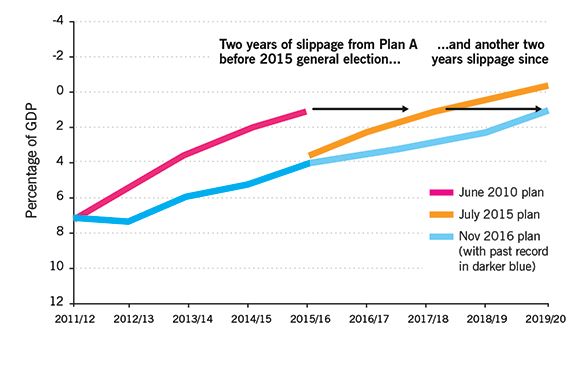

Make me pure, but not yet!

The date for closing the deficit has slipped—again

George Osborne posed as the unbending chancellor, who resolved to stick with the austere Plan A he set out in 2010. And he did make big cuts in many areas. But when forecasts for the economy, and with it tax receipts, were revised down during his first two years in office he took the pragmatic decision to give himself more time. The original plan to pay it down was a one-parliament job, but it steadily drifted into second. Now, with the post-referendum downgrade and a measure of extra public investment, his successor, Hammond, is proposing to to stretch out the squeeze on day-to-day spending into a third parliament. Even if he can deliver on all his public expenditure plans—some of which are extremely stretching—the public finances will remain in deficit until 2021/22 at the least.

Source: HM Treasury documentation (various years)

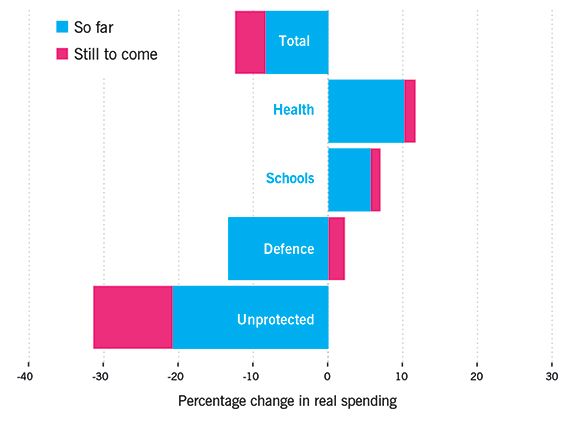

Squeezes all round, and a savaging for some:

Many services will end up being chopped by a third

Average direct expenditure by central government on public services will be 4 per cent lower in 2019–20 than in 2016–17. That comes on top of the 8 per cent real cut already delivered since 2010, making for total planned cuts of 12 per cent, a significant reduction by any measure. But such averages conceal more than they reveal, for the cuts vary wildly across fields. Indeed, over this parliament there are modest real increases for health, schools and defence, the last of which had been taking its share of the overall pain until recently. Between them, these services represent half of central government spending, and the smaller aid budget also has special protection. The money for schools and the NHS is less than they are used to, and less even they got in the harsh days after 2010.

The deepest cuts of all, however, apply to the other half of services-—which get no protection at all. These include prisons, policing and all the activities of local authorities which central government funds with grants. The average cut in stall here is 12 per cent, on top of the average 22 per cent in the years since 2010. By the time we are through, the cumulative cut will be nearly a third (32 per cent).

Source: HM Treasury documentation (various years)

The only dispute is how much money’s gone missing

After the Brexit vote, the pound tumbled and markets got jittery for a time, but there was no general slump. Brexit however—whatever it may turn out to mean—hasn’t happened yet. And both sets of forecasters retained on the public payroll are agreed the UK economy will, more likely than not, soon be smaller than it would have been if things had gone the other way. The Office for Budget Responsibility, the official watchdog on which Chancellor Philip Hammond relies when he’s setting tax and spending policies has revised down its forecast for growth through to the end of 2017 by 1.1 per cent, rising to 1.4 per cent by 2021. Some Brexiteers have rubbished that, arguing that this is a small number clouded in uncertainty. That is true, but uncertainty cuts both ways. The Bank of England, like many other commentators, has pencilled in an even sharper downgrade.

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Bank of England

Make me pure, but not yet!

The date for closing the deficit has slipped—again

George Osborne posed as the unbending chancellor, who resolved to stick with the austere Plan A he set out in 2010. And he did make big cuts in many areas. But when forecasts for the economy, and with it tax receipts, were revised down during his first two years in office he took the pragmatic decision to give himself more time. The original plan to pay it down was a one-parliament job, but it steadily drifted into second. Now, with the post-referendum downgrade and a measure of extra public investment, his successor, Hammond, is proposing to to stretch out the squeeze on day-to-day spending into a third parliament. Even if he can deliver on all his public expenditure plans—some of which are extremely stretching—the public finances will remain in deficit until 2021/22 at the least.

Source: HM Treasury documentation (various years)

Squeezes all round, and a savaging for some:

Many services will end up being chopped by a third

Average direct expenditure by central government on public services will be 4 per cent lower in 2019–20 than in 2016–17. That comes on top of the 8 per cent real cut already delivered since 2010, making for total planned cuts of 12 per cent, a significant reduction by any measure. But such averages conceal more than they reveal, for the cuts vary wildly across fields. Indeed, over this parliament there are modest real increases for health, schools and defence, the last of which had been taking its share of the overall pain until recently. Between them, these services represent half of central government spending, and the smaller aid budget also has special protection. The money for schools and the NHS is less than they are used to, and less even they got in the harsh days after 2010.

The deepest cuts of all, however, apply to the other half of services-—which get no protection at all. These include prisons, policing and all the activities of local authorities which central government funds with grants. The average cut in stall here is 12 per cent, on top of the average 22 per cent in the years since 2010. By the time we are through, the cumulative cut will be nearly a third (32 per cent).

Source: HM Treasury documentation (various years)