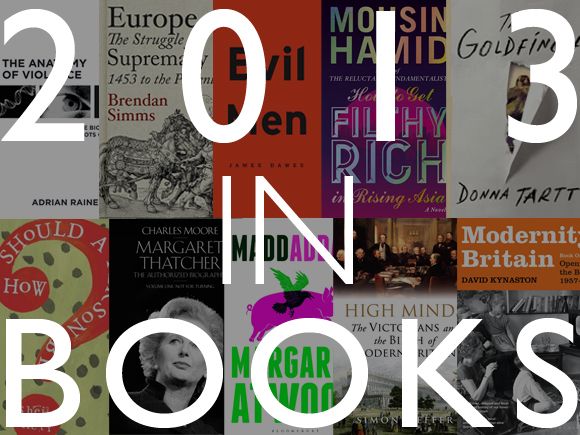

Here are ten books that Prospect writers particularly admired this year.

NON-FICTION

Europe: The Struggle for Supremacy, 1453 to the Presentby Brendan Simms (Allen Lane, £30) “At 690 pages it is big in heft and ambition, sweeping across half a millennium of European history,” wrote Josef Joffe in April. “Aficionados of the craft should cheer the arrival of Simms’s brainchild. There is nothing in the recent literature to match it. Not only has Simms bitten off a huge chunk of history, he has also mastered it with style and an awe-inspiring command of the literature (the footnotes run on for almost 100 pages). He deserves a prize just for this Herculean feat of synthesis. Another one might beckon for breaking the mould of traditional, that is, state-centred, diplomatic history. The narrative weaves together grand strategy and domestic politics, economics and ideology, and the European as well as global strands of a story that is about “us”—the west with its magnificent achievements and untold cruelties.” The Anatomy of Violence: The biological roots of crimeby Adrian Raine (Allen Lane, £25) “It is hard to think calmly about violence, and nobody knows that better than Adrian Raine, a distinguished neuroscientist who has devoted his career to uncovering the causes of human violence,” wrote Daniel Dennett in May. “He recognises that these are not just scientific questions, like uncovering the causal mechanisms of earthquakes, but also some of the most important ethical questions facing society. The Anatomy of Violence is a most valuable contribution to the current debates on these topics. Raine provides the details, and the evidential backing, for a host of distinctions that need to be drawn by those of us intent on reforming our obscenely unjust system of criminal justice.” High Minds: The Victorians and the Birth of Modern Britainby Simon Heffer (Random House, £30) “As a journalist, Heffer relishes a stand-up fight. The tone of this book is different,” wrote Dinah Birch in October. “Though he sees the Victorians in the light of his own conservatism, the work is not framed as a political intervention. Heffer’s admiration for a generation blessed with an unshakable confidence in the future tempers his habitually acerbic tone. Modesty is not a quality usually associated with his writing, but here a sense of the grandeur of what was accomplished in the face of formidable difficulty means that he adopts the role of chronicler and advocate, rather than polemicist. This is a serious book about the lasting value of seriousness. Engaging, and finally moving, it is a remarkable achievement.” Margaret Thatcher: The Authorised Biography, Volume 1by Charles Moore (Allen Lane, £30) “Long after names like Harold Macmillan and Harold Wilson have been reduced to essay topics for A-level history students,” wrote David Frum in June, “Thatcher will continue to inspire the passionate debate that still surrounds the most famous names in British history, from Wat Tyler to Winston Churchill. Charles Moore’s authorised biography is the source to which debaters on all sides will apply again and again for facts, insights, and interpretation.” Evil Menby James Dawes (Harvard, £19.95) “Evil Men explores the causes and effects of human wickedness,” wrote Raymond Tallis in June. “At its heart is a series of interviews that Dawes conducted with a group of Japanese war criminals who fought in the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-45. While he attempts to understand people for whom bayonetting civilians was something between an initiation rite and a training exercise, he also fears that understanding will trivialise what happened. It is because Dawes finds no ethical resting place that his relentlessly honest book is a moral act of the highest order. Required reading.” Modernity Britain: Opening the Box, 1957-59 by David Kynaston (Bloomsbury, £25) “[Of all the historians of postwar Britain] David Kynaston is perhaps the most ambitious and diligent,” wrote Jonathan Coe in July. “Underpinning his work is a profound scepticism of authority. Kynaston mistrusts “opinion-formers” and that mistrust extends to writers who seek to form their readers’ opinions. All his instincts, in other words, incline towards the freedom of orginary people to have their own voice and their own way of life. Both his politics and his philosophy of history are radically democratic.”FICTION

How Should A Person Be? by Sheila Heti (Harvill Secker, £15) “The best novels are not only statements about the world but products of the world as well,” wrote Richard Beck in February. “It’s not hard to see why How Should A Person Be? should be so confused by sex, so desperate for friendship, so enthralled by reality TV, and so bored by novels. Just look at the rest of us! “May the Lord have mercy on me,” Heti writes, “for I am a fucking idiot. But I live in a culture of fucking idiots.” The line, asking not for forgiveness or pardon but for mercy, is wise advice. It’s exhilarating to see Heti embrace her contemporaries, fucking idiots though they may be, with such anger, affection, and intelligence.” How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising AsiaBy Mohsin Hamid (Hamish Hamilton, £14.99) “To write one novel in second-person narrative may be regarded as a stunt; to write two looks like masochism,” wrote Rose Jacobs in April. “Mohsin Hamid has already proved his formal dexterity with The Reluctant Fundamentalist. In his new novel, he multiplies the feats. On top of the self-help conceit, Hamid adds a second formal trick, universalising his tale by leaving his characters nameless, his places untied to a map. That this enhances rather than detracts from the emotion of the story demonstrates the power of his prose.” The Goldfinchby Donna Tartt (Little, Brown, £20)“The Goldfinch has been 11 years in preparation, but in the epic range of its concerns with grief, loss, loneliness, fate, and the nature of good and evil, its rich cast of characters, and its broad social canvas, it bears comparison with Proust, Dickens, Dostoevsky and Nabokov,” wrote Elaine Showalter in October. “Although the novel is 784 pages long, it is meticulously structured and paced, and reading it is an enthralling experience of total immersion in Tartt’s vision and voice. A beautiful and important book.” MaddAddamby Margaret Atwood (Bloomsbury, £18.99) “We freely call Madame Bovary or Pride and Prejudice or American Pastoral ‘realistic’ without any personal knowledge of the circumstances in which they are set,” wrote Ruth Franklin in September. “What we believe we recognise in such works is actually testimony to the authors’ imaginative creation of a plausible world. And this is also the case for Atwood’s trilogy, of which MaddAddam is now the final installment. Atwood prefers to call these works ‘speculative fiction’ to avoid associations with the B-movie images ‘science fiction’ tends to evoke. For all their pleasures, the purpose of these novels is deeply serious. Like all literature, they strive to teach us how to live—or in this case, how not to live. And anyone who reads them as purely ‘science fiction’ has not been paying attention to the news. Ten years have passed since this trilogy began, and the future has already begun to catch up with it.” Read MoreOur most read articles of 2013Prospect's picks of 2013The best Prospect articles of 2012The most read Prospect articles of 2012